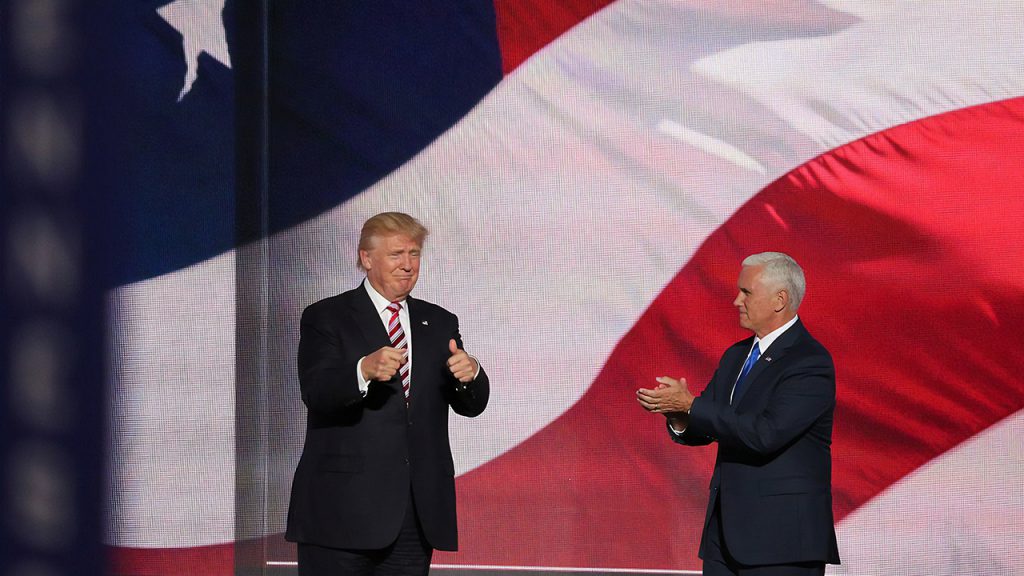

Donald Trump was elected president promising to use protectionist measures, if necessary, to bring jobs back to America. Economists warn that raising tariffs reduces trade and hurts the economy. The Smoot-Hawley Act of 1930 is blamed for intensifying the Great Depression, and the lesser-known McKinley Tariff of 1890 provides an instructive lesson on how protectionist policies can impact the stock market and politics.

In 1888, the protectionist Republican Benjamin Harrison defeated the pro-trade Democrat Grover Cleveland. Cleveland won the popular vote, but Harrison won the electoral college. Harrison increased government spending past the billion-dollar mark for the first time in history, and helped to pass the McKinley Tariff of 1890, which raised tariffs around 50%.

Donald Trump was elected president promising to use protectionist measures, if necessary, to bring jobs back to America. Economists warn that raising tariffs reduces trade and hurts the economy. The Smoot-Hawley Act of 1930 is blamed for intensifying the Great Depression, and the lesser-known McKinley Tariff of 1890 provides an instructive lesson on how protectionist policies can impact the stock market and politics.

In 1888, the protectionist Republican Benjamin Harrison defeated the pro-trade Democrat Grover Cleveland. Cleveland won the popular vote, but Harrison won the electoral college. Harrison increased government spending past the billion-dollar mark for the first time in history, and helped to pass the McKinley Tariff of 1890, which raised tariffs around 50%.

Donald Trump’s inauguration speech vowed to return protectionism in an effort to not only bolster employment, but to recapture positions that have migrated overseas. His initial defense against the outflow of American jobs to foreign countries is to raise border taxes on foreign goods imported into the US by renegotiating the NAFTA Agreement. Spearheading this charge is a specific tariff, and perhaps one might say, penalty, on Mexico, by levying a 20% fee on goods produced by Mexico.

Rather than singling out a specific country, Trump should study the effects of the Tariff Act of 1930, otherwise known as the Smoot–Hawley Tariff, to see how this worked out for the economy in the past.

Donald Trump’s inauguration speech vowed to return protectionism in an effort to not only bolster employment, but to recapture positions that have migrated overseas. His initial defense against the outflow of American jobs to foreign countries is to raise border taxes on foreign goods imported into the US by renegotiating the NAFTA Agreement. Spearheading this charge is a specific tariff, and perhaps one might say, penalty, on Mexico, by levying a 20% fee on goods produced by Mexico.

Rather than singling out a specific country, Trump should study the effects of the Tariff Act of 1930, otherwise known as the Smoot–Hawley Tariff, to see how this worked out for the economy in the past.

Unemployment was already high at 8% in 1930 when the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act was passed as a result of the agricultural industries. But the law failed to tackle the true issues quick enough, and employment rates jumped to 16% in 1931, and 25% in 1932–33. The graph below shows the increase in number of people unemployed in the US from 1930 to 1933.

The Great Depression, which started in the US, cast a long shadow and its impact was felt by major trading partners across the ocean. The 1930s were plagued with stock market crashes, high unemployment, bank failures, poverty, and bankruptcy. Economists blame the protectionist ideology for many of the issues during this decade. After World War II, nations agreed to promote more free trade and stimulate global growth so as to avoid a second depression. If we can learn from this example, I would hate to see history repeat itself. Many global economies are still fragile from the financial crisis of 2008. Is Trump ready to put us in another one?

Today, the future of energy prices is as uncertain as ever. Whereas in the 1970s, there was a fear that the supply of oil could decline dramatically, causing future oil prices to rise, fracking and other technological innovations have increased oil reserves to levels never before seen in history. At the same time, natural gas is becoming a clean substitute for petroleum, and because of concerns over global warming, solar power and battery technology are improving dramatically as attempts to end the economy’s dependence on carbon-based energy increase. Although coal is one of the dirtiest of energy resources, it remains an important source of power for electricity plants, especially since many countries want to eliminate any reliance on nuclear power.

Today, the future of energy prices is as uncertain as ever. Whereas in the 1970s, there was a fear that the supply of oil could decline dramatically, causing future oil prices to rise, fracking and other technological innovations have increased oil reserves to levels never before seen in history. At the same time, natural gas is becoming a clean substitute for petroleum, and because of concerns over global warming, solar power and battery technology are improving dramatically as attempts to end the economy’s dependence on carbon-based energy increase. Although coal is one of the dirtiest of energy resources, it remains an important source of power for electricity plants, especially since many countries want to eliminate any reliance on nuclear power.

Energy Resources During the Past 750 Years

From the 1200s to the 1800s, the economy’s primary energy resource was firewood, with coal and lamp oil acting as secondary resources. Each, in its own way, provided different types of energy for cooking, heating and power. GFD’s data on firewood prices begins in 1252, coal prices begin in 1447, and lamp oil price data begins in 1272. Although firewood was the primary source for energy from the 1200s to the 1800s, it was gradually replaced by electricity and gas in the 1800s as energy was brought directly into the home. As the graph below shows, although there were periods when the price of firewood rose dramatically, the price of firewood also stayed the same for centuries.

As the use of firewood declined in the 1800s, in part because the forests of Europe and America were exhausted, coal become more prominent and by the 1900s, petroleum replaced coal as the primary source of energy. In the 1700s, whale oil replaced lamp oil as whalers from New Bedford and other parts of New England searched global oceans for whales to kill and convert their blubber into oil. Whaling became the principal industry of New England making the area rich. Had the world remained dependent on whale oil, whales would have become extinct long ago.

In the 1860s, petroleum oil was discovered in Pennsylvania and quickly replaced whale oil as a source of energy. When oil was first produced in Pennsylvania in 1859, a barrel of oil sold for $20, but because of oversupply, the price quickly fell to 10 cents by the end of 1861, making it a cheap substitute for whale oil.

Overnight the whaling business went into steady decline, with production falling by 70% between 1854 and 1865, leaving us Moby Dick, and saving whales from extinction. By combining historical data for coal, coal gas, firewood, lamp oil, whale oil, petroleum oil and natural gas, GFD has created a commodity index of energy prices that covers the past 750 years.

Long-term Trends in Commodity Prices

Several interesting facts emerge from a long-term analysis of commodity prices. Industrial commodities, basically metals and non-food agriculturals, have consistently risen in price less than other commodities. In fact, the dip in industrial commodity prices in the 1930s returned the index to where it had been in 1550! Since then, industrial commodity prices have increased faster than agriculturals, but still not as fast as energy prices.

Of the three major commodity indices that GFD calculates for energy, agriculturals and industrials, the energy index has increased the most over the past 750 years. Between 1252 and 1970, both energy and agricultural prices increased by a factor of 60 while industrial commodity prices increased by only a factor of six. During those 700 years, agricultural and energy prices increased in line with one another with few dramatic swings in relative prices.

The Surprising Interplay Between Coal and Oil Prices

The chart below provides a comparison of the behavior of two of the underlying components of the energy price index, oil, represented by the lower price line since 1800 and coal, which has shown a steady uptrend over the past few centuries.

Few people would have guessed that over the long term, coal has shown such a consistent increase in its price, following a 500-year trendline that started in the early 1500s. Even more surprising is the fact that oil prices, as represented by lamp oil, whale oil and petroleum, showed no tendency to increase from the late 1500s to the 1930s. When petroleum oil was first produced in Pennsylvania, the price of oil went through a series of wild swings, starting at $20 in 1859, collapsing down to 10 cents in 1861, then rising back to $11 in 1864, and gradually declining in price until the end of the 1800s. During the 1900s, both oil and coal prices increased steadily, but oil prices have increased five times as fast as coal prices over the past 100 years because of increased demand for oil relative to coal.

The Future of Commodity Prices

In our annual review of global stock markets, we noticed that a relatively large number of countries put in what could be a bear market bottom in 2016. If this is true, investors should expect that global markets will continue a bull market run in 2017 rather than forming a top that leads to a bear market.

Global Financial Data has data on bull and bear markets on 100 countries beginning in 1693. With this data, we have been able to track bull and bear markets during the past three centuries. We define a bear market as a decline of 20% or more in a country’s primary stock market average and a bull market as an increase in the market of 50% or more. Although a 20% decline is a commonly accepted decline to indicate a bear market, there are no clear rules on what constitutes a bull market. The reason we settled on a 50% increase is that if a market declines by 20% (from 1000 to 800), it would have to increase by at least 50% (from 800 to 1200) to rise 20% above the previous market top. Any changes of a smaller magnitude are treated as either a bear market rally or a bull market contraction.

In our annual review of global stock markets, we noticed that a relatively large number of countries put in what could be a bear market bottom in 2016. If this is true, investors should expect that global markets will continue a bull market run in 2017 rather than forming a top that leads to a bear market.

Global Financial Data has data on bull and bear markets on 100 countries beginning in 1693. With this data, we have been able to track bull and bear markets during the past three centuries. We define a bear market as a decline of 20% or more in a country’s primary stock market average and a bull market as an increase in the market of 50% or more. Although a 20% decline is a commonly accepted decline to indicate a bear market, there are no clear rules on what constitutes a bull market. The reason we settled on a 50% increase is that if a market declines by 20% (from 1000 to 800), it would have to increase by at least 50% (from 800 to 1200) to rise 20% above the previous market top. Any changes of a smaller magnitude are treated as either a bear market rally or a bull market contraction.

Have Emerging Markets Ended a Four-year Bear Market?

One country actually suffered two bear markets in 2016, Venezuela, which ended a 30% bear market in July, rallied 228% into December, then suffered a 26% decline over a period of three weeks. These fluctuations occurred in the country with the highest inflation in the world, and adjusting for inflation, the results were quite different. During 2016, the Venezuela Bolivar Fuerte (sic) fell against the US Dollar by about 75%. Measured in US Dollars, the Caracas Stock Exchange Index declined by 73% between June 2015 and December 2016. The highest denomination banknote in Venezuela, the 100 Bolivar, is worth about three cents. I think I can safely say that Venezuela has not hit a bottom yet.| Country | Bull Top | Change | Bear Bottom | Change | 2016 Recovery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abu Dhabi | 9/18/2014 | 144.93 | 1/21/2016 | -28.59 | 21.66 |

| Belgium | 4/13/2015 | 104.31 | 2/11/2016 | -21.25 | 16.30 |

| Brazil | 11/4/2010 | 133.58 | 1/20/2016 | -48.43 | 59.99 |

| China | 6/12/2015 | 165.15 | 2/29/2016 | -48.02 | 15.53 |

| Colombia | 11/5/2010 | 151.96 | 1/18/2016 | -51.78 | 28.75 |

| Croatia | 2/11/2011 | 84.84 | 1/18/2016 | -32.55 | 26.54 |

| Czech Republic | 4/15/2010 | 107.51 | 6/27/2016 | -39.42 | 16.65 |

| Egypt | 9/7/2014 | 147.67 | 1/21/2016 | -48.26 | 147.74 |

| France | 4/27/2015 | 92.87 | 2/11/2016 | -25.28 | 24.47 |

| Germany | 4/10/2015 | 120.19 | 2/11/2016 | -29.00 | 26.40 |

| Greece | 3/1/2014 | 187.51 | 2/11/2016 | -67.81 | 45.99 |

| Hong Kong | 4/28/2015 | 75.03 | 2/12/2016 | -35.59 | 20.09 |

| India | 1/29/2015 | 95.60 | 2/11/2016 | -22.67 | 16.01 |

| Iraq | 10/4/2011 | 63.50 | 6/16/2016 | -73.18 | 28.75 |

| Italy | 4/15/2015 | 91.29 | 6/27/2016 | -30.74 | 22.61 |

| Japan | 8/10/2015 | 143.17 | 2/12/2016 | -29.27 | 26.91 |

| Kazakhstan | 9/3/2014 | 55.26 | 1/21/2016 | -39.12 | 69.89 |

| Kuwait | 6/24/2008 | 70.82 | 1/26/2016 | -68.47 | 16.46 |

| Luxembourg | 4/14/2015 | 73.02 | 2/11/2016 | -34.48 | 41.39 |

| Mongolia | 2/25/2011 | 626.20 | 5/5/2016 | -68.18 | 17.09 |

| Namibia | 5/5/2015 | 199.62 | 1/20/2016 | -36.31 | 38.52 |

| Netherlands | 4/13/2015 | 85.92 | 2/11/2016 | -24.28 | 24.42 |

| Nigeria | 7/9/2014 | 118.19 | 1/19/2016 | -47.82 | 19.68 |

| Norway | 4/15/2015 | 72.83 | 1/20/2016 | -26.35 | 29.50 |

| Oman | 1/16/2011 | 66.38 | 1/21/2016 | -30.74 | 18.81 |

| Peru | 4/2/2012 | 298.29 | 1/20/2016 | -63.09 | 75.34 |

| Philippines | 4/10/2015 | 376.85 | 1/21/2016 | -25.14 | 12.43 |

| Poland | 4/28/2011 | 120.89 | 1/20/2016 | -42.90 | 16.32 |

| Qatar | 9/18/2014 | 239.24 | 1/18/2016 | -40.65 | 22.54 |

| Romania | 8/10/2015 | 83.09 | 1/18/2016 | -21.21 | 17.71 |

| Saudi Arabia | 9/9/2014 | 169.96 | 10/3/2016 | -51.42 | 33.12 |

| Singapore | 5/22/2013 | 143.72 | 1/21/2016 | -26.50 | 12.75 |

| Spain | 4/13/2015 | 99.78 | 2/11/2016 | -34.95 | 20.49 |

| Sweden | 4/27/2015 | 109.56 | 2/11/2016 | -22.84 | 22.79 |

| Ukraine | 8/1/2014 | 65.89 | 5/24/2016 | -54.63 | 23.17 |

| Venezuela | 6/13/2015 | 100.40 | 12/10/2016 | -73.34 | 14.07 |

| Zimbabwe | 8/1/2013 | 133.18 | 6/17/2016 | -59.95 | 54.76 |

| MSCI EAFE | 7/3/2014 | 52.30 | 2/12/2016 | -25.21 | 12.84 |

| MSCI Emerging | 5/2/2011 | 153.96 | 1/21/2016 | -42.93 | 5.24 |

| MSCI Europe | 5/21/2015 | 53.45 | 6/27/2016 | -25.53 | 12.89 |