25 years ago: May 1994

S&P 500: 456.50 (vs. 2881.40 in 05/2019)

10-year U.S. Government Bond Yield: 7.17% (vs. 2.47% in 05/2019)

Gold: $387.60 (vs. $1287.10 in 05/2019)

Oil: $18.295 (vs. $61.65 in 05/2019)

GBP/USD: 1.5105 (vs. 1.2999 in 05/2019)

US GDP: $7,115 billion (vs. $21,062 billion in 03/2019)

US Population: 260 million (vs. 328 million in 2019)

05/04/1994: The White House recruits central banks around the world to buy the flagging dollar in the biggest show of force currency markets have seen in a decade. Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and PLO leader Yasser Arafat sign a peace accord regarding Palestinian autonomy granting self-rule in the Gaza Strip and Jericho.

05/05/1994: American teenager Michael P. Fay is convicted and caned for vandalism.

05/06/1994: Former Arkansas state worker Paula Jones files a lawsuit against United States President Bill Clinton, alleging that he had sexually harassed her in1991. Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom and French President Franois Mitterrand officiate at the opening of the Channel Tunnel.

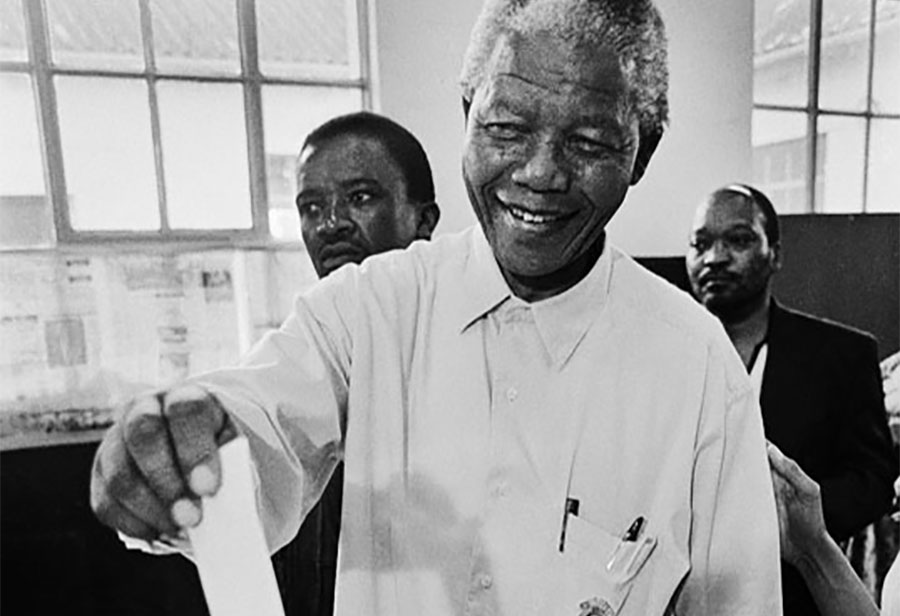

05/10/1994: Nelson Mandela is inaugurated as South Africa’s first black president.

05/17/1994: The Fed boosts short-term interest rates 1/2 percentage point.

05/24/1994: Four men convicted of bombing the World Trade Center in New York in 1993 are each sentenced to 240 years in prison.

05/26/1994: Clinton renews China’s trading status with the U.S. while conceding that Beijing hasn’t met human-rights standards he set last year.

50 years ago: May 1969

S&P 500: 103.46 (vs. 2881.40 in 05/2019)

10-year U.S. Government Bond Yield: 6.56% (vs. 2.47% in 05/2019)

Gold: $43.075 (vs. $1287.10 in 05/2019)

Oil: $3.21 (vs. $61.65 in 05/2019)

GBP/USD: 2.3885 (vs. 1.2999 in 05/2019)

US GDP: $993 billion (vs. $21,062 billion in 03/2019)

US Population: 205 million (vs. 328 million in 2019)

05/1969: Bear Markets begin in Spain, Great Britain, Switzerland, Argentina and South Africa

05/05/1969: Money/credit pinch started taking bite out of economy. Westec Corp. plunged $36.50 on ASE as trading resumed after 2 years, 8 months, 11 days.

05/08/1969: Viet Cong offered peace plan.

05/10/1969: Vietnam War: The Battle of Dong Ap Bia begins with an assault on Hill 937. It will ultimately become known as Hamburger Hill.

05/15/1969: People’s Park: California Governor Ronald Reagan has an impromptu student park owned by University of California at Berkeley fenced off from student anti-war protestors, sparking a riot called Bloody Thursday.

/05/17/1969: Venera program: Soviet Venera 6 begins its descent into the atmosphere of Venus, sending back atmospheric data before being crushed by pressure.

05/22/1969: Apollo 10’s lunar module flies within 8.4 nautical miles (16km) of the moon’s surface.

100 years ago: May 1919

S&P 500: 9.212 (vs. 2881.40 in 05/2019)

10-year U.S. Government Bond Yield: 4.67% (vs. 2.47% in 05/2019)

Gold: $20.67 (vs. $1287.10 in 05/2019)

Oil: $4.05 (vs. $61.65 in 05/2019)

GBP/USD: 4.6325 (vs. 1.2999 in 05/2019)

US GDP: $84 billion (vs. $21,062 billion in 03/2019)

US Population: 104 million (vs. 328 million in 2019)

05/01/1919: Third Anglo-Afghan War: Amanullah led a surprise attack against the British. Mt Kelud in East Java erupts with a death toll of around 5,000 people.

05/04/1919: May Fourth Movement: Student demonstrations take place in Tiananmen Square in Beijing, China, protesting the Treaty of Versailles, which transferred Chinese territory to Japan.

05/07/1919: German Delegation presented with the terms of the Treaty Of Versailles

05/15/1919: Greek invasion of Smyrna. During the invasion, the Greek army kills or wounds 350 Turks. Those responsible are punished by the Greek Commander Aristides Stergiades. The Winnipeg General Strike begins. By 11:00, almost the whole working population of Winnipeg, Manitoba had walked off the job.

05/16/1919: A naval Curtiss aircraft NC-4 commanded by Albert Cushing Read leaves Trepassey, Newfoundland, for Lisbon via the Azores on the first transatlantic flight.

05/29/1919: Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity is tested (later confirmed) by Arthur Eddington and Andrew Claude de la Cherois Crommelin.

200 years ago: May 1819

S&P 500: 1.549 (vs. 2881.40 in 05/2019)

10-year U.S. Government Bond Yield: 4.688% (vs. 2.47% in 05/2019)

Gold: $19.39 (vs. $1287.10 in 05/2019)

GBP/USD: 4.5455 (vs. 1.2999 in 05/2019)

US GDP: $727 million (vs. $21,062 billion in 03/2019)

US Population: 9.379 million (vs. 328 million in 2019)

05/04/1819: City Bank, Baltimore, failed, cashier resigned

05/22/1819: The SS Savannah leaves port at Savannah, Georgia, United States, on a voyage to become the first steamship to cross the Atlantic Ocean. The ship arrived at Liverpool, England, on June 20.

05/23/1819: Princess Victoria born.

05/25/1819: The Argentine Constitution of 1819 is promulgated.

© 2019 Global Financial Data. Please feel free to redistribute this Events-in-Time Chronology and credit Global Financial Data as the source.

Source for Image of Nelson Mandela

Global Financial Data has added over 30 new Consumer Price and Producer Price Indices to its database as well as 25 new Unemployment Rates.

Canada has one of the ten largest markets in the world. With a capitalization of over $2 trillion and over 3300 listed companies, and many of its companies listed in New York, Canadian companies have played an important role in the global economy over the past 150 years. Canadian companies have listed in London since 1692 and in New York since the 1860s. Brokers began trading shares at the Exchange Coffee House in Montreal in 1832 and the Montreal Stock Exchange was founded in 1874. The Toronto Stock Exchange was begun by the Association of Brokers in 1852, was formally founded in 1861 and incorporated in 1878.

Global Financial Data has collected data on companies from South Africa that listed in London during the 1800s and 1900s. Between 1835 and 1985, over 400 South African companies listed in London. Before 1890, there were fewer than 20 South African companies in London, but once gold was discovered in the 1890s, the number of South African companies mushroomed, increasing to 45 in 1890 and over 100 by 1902. South African companies also listed in Paris where they traded on the Coulisse Exchange as well as in Amsterdam, Berlin and other stock exchanges because European investors wanted to profit from the South African gold rush.