Global Financial Data has added data on individual stocks from the Copenhagen stock market between 1871 and 1937 to the database. This provides a history of Danish stocks that was previously unavailable. In the midst of putting together this data, we discovered a forgotten stock market bubble of shipping stocks during World War I.

This bubble followed the classic pattern of a dramatic rise followed by a crash, but we have never seen this bubble mentioned in any of the sources we have consulted. In many ways, this was a “rational” bubble since dividends paid by the shipping companies rose dramatically during World War I and then collapsed after the war. The details of this bubble are discussed below.

Global Financial Data has added data on individual stocks from the Copenhagen stock market between 1871 and 1937 to the database. This provides a history of Danish stocks that was previously unavailable. In the midst of putting together this data, we discovered a forgotten stock market bubble of shipping stocks during World War I.

This bubble followed the classic pattern of a dramatic rise followed by a crash, but we have never seen this bubble mentioned in any of the sources we have consulted. In many ways, this was a “rational” bubble since dividends paid by the shipping companies rose dramatically during World War I and then collapsed after the war. The details of this bubble are discussed below.

Data Sources

Global Financial Data went to a number of sources in order to put together 65 years of history on the Danish stock market. Theodor Green published Fonds og Aktier beginning in 1883 and periodically in the years that followed. The books provided price data for Danish stocks as well as shares outstanding and dividend data. In 1893, Danmarks Statistik began providing data on individual stocks and dividends of individual companies in its Statistisk Aarbog, and continued to provide this data until 1937. Danmarks Statistik began calculating its own index of Danish stock prices after World War I, so collecting and organizing this data enables us to put together an index of Danish stock prices going back 45 years before the Danish index was calculated. Global Financial Data has put together a database of almost 100 companies to create Danish indices that previously did not exist. With this data, GFD has calculated a cap-weighted price index and return index as well as the dividend yield on Danish stocks between 1871 and 1937.The Forgotten Bubble

Danish shipping stocks were an important part of the Danish stock market, but overall represented a small portion of the total stock market capitalization. As the chart below shows, transports represented around 10% of the Danish stock market. The two primary sectors on the Copenhagen stock exchange were banks and telecommunications. The banks were represented by Denmark’s four main banks, the Nationalbank, the Privatbank, the Landmandsbank and the Handelbank. The Great Northern Telegraph Co., which listed on the London Stock Exchange, was the largest company in Denmark, representing from 20 to 30 percent of the Danish stock market’s capitalization. It should be remembered that because Denmark is largely a collection of islands and peninsulas, railroads never played a major role in the Danish economy. There were private tramways in the main cities, but they were eventually nationalized by the government. Almost all the transport companies in Denmark were shipping companies and the largest of these was the United Steamship Co. (Forenede Dampskibsselskabs A/S). If you look at the Sector Stacked Graph below, the bubble in transport stocks between 1914 and 1921 sticks out like a sore thumb. Shipping revenues and profits rose dramatically during World War I, leading to higher dividends and higher stock prices. Just to use the United Steamship Co. as an example, the company’s dividend rose from 8% in 1914 to 60% in 1919 then collapsed to 5% by 1922. Other steamship companies provided even more dramatic changes.Denmark in World War I

Denmark was in a difficult position when World War I began. Denmark was a neutral country even before the onset of the war. Denmark had been defeated in 1864 in its war with Prussia. After the war, Denmark lost the territory of Northern Schleswig, which had a majority Danish population, to Prussia and even though Denmark would have liked to regain control over Northern Schleswig, the political reality was that Denmark was too small to challenge Prussia politically or economically. Consequently, neutrality became a part of the Danish mentality. Before World War I, Denmark was highly dependent on imports and exports with ninety percent of exports derived from agriculture in 1913. Denmark built up a large shipping fleet that carried 70% of its shipping between foreign ports. Denmark’s shipping industry was as large as Spain’s, and it was the fourteenth largest merchant marine in the world when World War I began. The Danish merchant marine’s net tonnage doubled in size between 1885 and 1914, and most of this investment was in more efficient steam shipping and motor vessels. The Danish shipping industry was dominated by Det Forenede Dampskib-selskab (United Steamship Company of Copenhagen, now known as DFDS) which represented three-eighths of Danish shipping in 1914. The company was founded on December 11, 1866 when Carl Frederik Tietgen merged the three largest steamship companies into a single company. Since its founding in 1866, the company has consistently paid a dividend over 7% reflecting the profitability of the company and the sector.Conclusion

The Danish Shipping Stock Market bubble of 1914-1920 has long been forgotten, but is a dramatic reminder of how war, politics and the economy affect the stock market. Denmark’s unique geographical and political situation during World War I enabled it to profit from the changes that occurred during the war. The profits were concentrated in the shipping industry and it alone benefitted from the war while the rest of the economy reaped few benefits. The price increases the shipping stocks enjoyed were justified by the dramatic increase in profits and dividends that occurred. In some cases, profits and dividends increased ten-fold during the war and prices responded accordingly. When the war was over and depression followed, share prices collapsed. By any stretch of the imagination, it was a “rational” bubble. The data for the Copenhagen stock exchange, both the data for the individual companies and the GFD Indices that were calculated based upon those indices are available to all subscribers to the stock database. If you would like to access this data and currently do not have access, please feel free to call one of our sales representatives at 877-DATA-999 or 949-542-4200.The Course of the Exchange made the first attempt to break the stock market down into sectors in 1811 when it expanded its coverage of stocks to include shares other than the three sisters, the Bank of England, South Sea stock and East India Company that dominated the English stock market in the 1700s.

Twenty securities were listed in The Course of the Exchange from 1747 to 1811 as a group. On January 1, 1811, coverage expanded to two pages and stocks were divided into different sectors: canals, docks, assurance, water works and miscellaneous companies. On August 30, 1811, Iron Railways were added as a sector, including the Surrey, Cheltenham and Severn and Wye Iron Railroads. By 1845 there were not 3 railroads but 244 railroads.

Mines, Bridges and Literary Institutions were added in 1817. Gas, Light & Coke Companies received a separate classification in 1819, and by 1825, The Course of the Exchange had 11 sectors: Canals, Docks, Assurance, Bridges, Water Works, Literary Institutions, Mines, Gas Light & Coke Companies, Roads, Iron Railways and Miscellaneous as the main components of the British stock market. Oddly enough, there were 11 sectors in 1825 as there are 11 sectors in the GICS system today.

As the stock market evolved, so did the sector classification. Railroads represented over 80% of the stock market by the middle of the 1800s. When stock market indices were introduced in the 1800s, there were two types of indices, railroads and industrials. Over time other sectors were introduced and in 1999, MSCI and S&P created the Global Industry Classification System (GICS) which broke the stock market down into 10 sectors. Since then Real Estate has increased the number of sectors to 11 and Telecommunications has become Communications. Who knows what the GICS will look like 10 years from now.

United States sectors 1800 to 2018

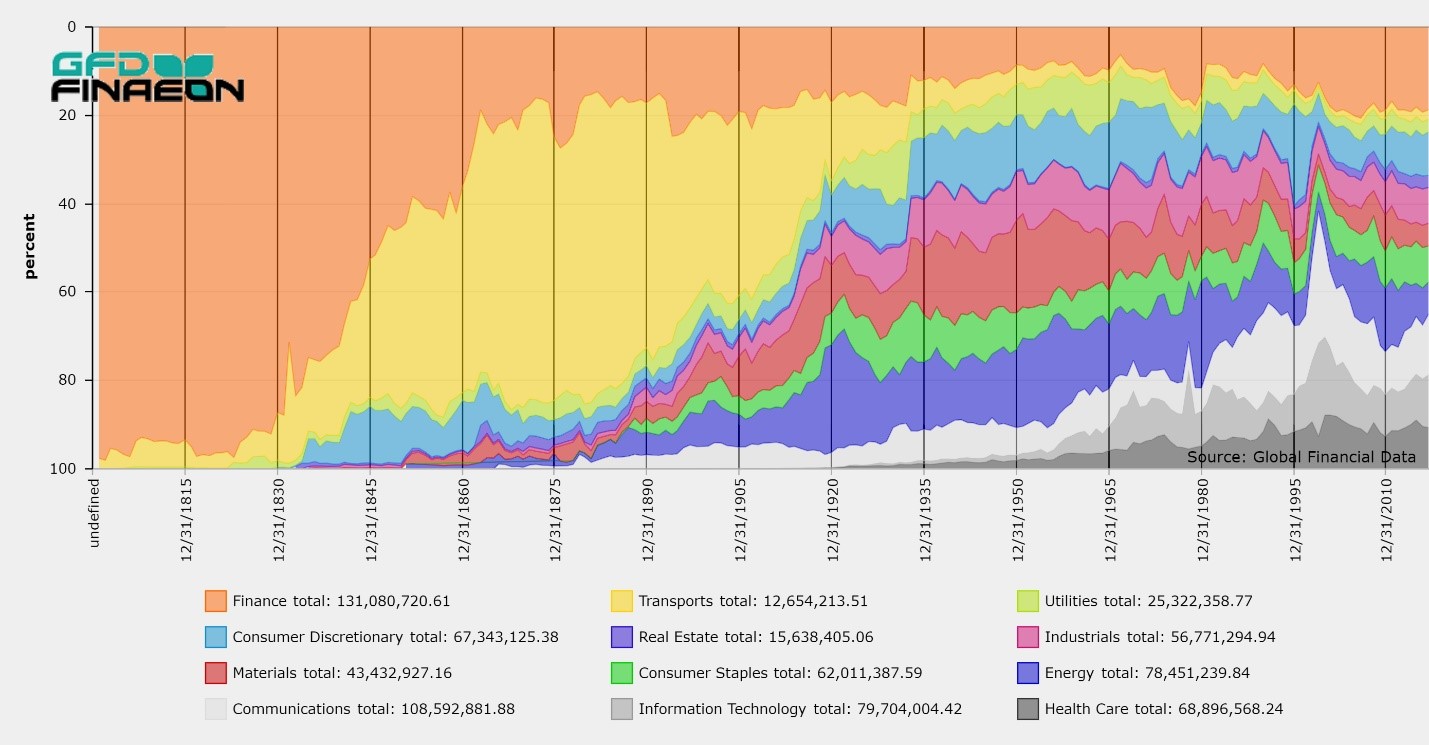

They say a picture is worth a thousand words, and that is certainly true of the picture below. In fact, maybe it is worth 3000 words. The graph shows the evolution of the 12 GFD sectors that make up the American economy over the past 200 years. In the 1800s, finance companies and transports largely dominated the stock market, but starting in the 1880s, other sectors began to grow in size, squeezing out finance and transports until today transports represent such a small portion of the total capitalization of the stock market that GICS doesn’t even recognize it as a sector.

Global Financial Data recognizes 12 sectors rather than 11. Because of the historical importance of transports, GFD treats transports as a separate sector, not as part of the industrial sector. From canals to railroads to airlines, transports have been and always will be an important sector of the stock market. The graph below illustrates the capitalization of each sector based upon stocks included in the U.S. Stocks Database.

Finance

In 1791, finance was the only sector listed on the stock exchange as banks and then insurance companies were provided funding by investors. For the first 50 years of the stock market’s existence, finance was the stock market. Until 1836 when the second Bank of the United States lost its charter, the Bank of the United States as a company was a giant among a sea of minnows.

Banks and insurance companies continued to grow after the Bank of the United States lost its charter in 1836, but at a slower pace than other sectors, especially Transports, and Finance shrank to 20% of the stock market by the Civil War. Finance maintained its 20% share until the Great Depression when the collapse of the banking sector and the severe government restrictions on banks after the 1930s reduced the Finance sector to about 10% of the total capitalization by the 1960s.

Starting in the 1980s, the government allowed banks to cross state lines, expand their business, and consolidate the industry into a small number of large firms rather than thousands of small banks. Unitary banking in which a bank was allowed to have only one physical location in the country was abolished. The finance sector grew until it reached over 20% of the total capitalization of the stock market in 2008 when the financial crisis hit and shrank it back in size. Nevertheless, banks and insurance companies have maintained their 20% share of the stock market since 2008 and probably will do so for some time to come.

Transports

In the 1800s, transports were the most important sector of the stock market. Today, transports are a footnote and have lost their status as a sector. Nevertheless, because historically transports represented a majority of the stock market, GFD has given them sector status.

In the beginning, there were turnpikes and canals. Only a handful of the turnpikes had a capitalization over $1 million, and unlike the United Kingdom, canals were unable to connect the nation’s rivers to provide a national transportation system.

The real beginning of the growth of transports was in 1828 when the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad came into existence. The United States was covered with land and the railroads could go where no canals could reach. Consequently, from the Civil War until 1900, railroads represented over half of the capitalization of the United States stock market. Since most banks and insurance companies were traded over-the-counter, railroads represented over 80% of trades on the New York Stock Exchange. Railroads not only transformed the American economy, they transformed the stock market. American railroad shares were traded in London, Paris, Amsterdam and other bourses as Europeans invested in the American “emerging market.” Never again would any industry dominate the stock market the way railroads did in the 1800s.

Once the transcontinental railroads were built, there was little to add to the network of railroads that crisscrossed the country, and when the automobile was born, railroads’ share of the stock market could only shrink. Most local tramways were taken over by local governments, but the national railroads remained in private hands.

In European countries, the railroads were nationalized. Belgium’s railroads were built by the state, Germany’s railroads were nationalized in the 1870s and Britain’s in 1947. Although passenger service has been nationalized through Amtrak, railroads remain an important portion of transportation in the United States, as do airlines and trucks, but transports will never regain their status as a dominant sector in the American economy.

Utilities

Utilities have played an important, though consistently small role in the American economy. Although local tramways were often treated as a utility, we treat tramways as a transportation company. Telecommunication companies such as AT&T and Western Union were part of the Dow Jones Utilities in the 1930s, but these firms are in the communication sector in GFD.

Utilities represented a sliver of the American economy until the 1920s. Thousands of local utilities were strung across the country, but in the 1920s, utilities were absorbed by holding companies to create large corporations that drove the stock market boom of the 1920s. Tramways were absorbed into the utilities that provided power, transportation and telephones to local communities.

When the stock market crashed in the 1930s, many of the utility companies were overleveraged and they collapsed. The government began to regulate the utilities and they shrank in size to a managed portion of the American economy. Because the utilities are regulated, it is unlikely they will gain much market share in the future.

Consumer Discretionary

The early growth of the consumer discretionary sector came from the establishment of mills that produced textiles in New England. The mills took advantage of the power the rivers provided to drive the spindles that produced clothing for the rest of the country.

It was only after 1900 that the consumer discretionary sector began to grow again as automobiles began to take over personal transportation and large retail stores such as Sears replaced the local shops that people had grown up with. The consumer was largely born in the 1920s and has remained a consistent 10-15% of the American Stock market since the 1920s.

It should also be remembered that a good portion of consumer discretionary stocks have been transferred to the Communications sector. Because the internet has transformed communications to make them something that can be streamed rather than purchased on vinyl or seen in a theater, communications has become a sector unto itself. For this reason, consumer discretionary is unlikely to grow over time.

Real Estate

Real Estate has never been an important sector in the American stock market. Most of its growth has occurred in the past 20 years as real estate investment trusts have become an efficient way of managing properties.

Nevertheless, as a sector, GFD has data for real estate back to the 1830s. Many investors treat real estate as a separate investment asset class from stocks, bonds and bills and with the bubble in real estate that occurred in the 2000s, there is an interest in real estate as an asset class that didn’t exist in the twentieth century.

The problem with tracking real estate as an asset class is that property is so diversified and individualistic that few reliable indictors of returns to real estate exist. However, there have been real estate investment companies listed on the stock market since the 1830s and they can provide valuable insights to the return on property over the past 180 years. Real estate as a stock market sector can provide insights that indices put together from sales of property are unable to capture.

Industrials

Industrial companies produce goods for other businesses, not for individuals. When the Dow Jones Industrial Average was born in 1896, industrials included everything other than finance, transports and utilities. The New York Times had two indices, Railroads and Industrials. Dow Jones had three, adding utilities in the 1920s. Over time, “industrials” have been broken up into sectors that didn’t exist 100 years ago. Consumer stocks, materials and energy, health care and information technology are treated as separate sectors and industrial stocks are mainly companies that produce goods for other businesses. Industrials include machinery, electrical equipment, aerospace and commercial services.

The industrial sector grew until the 1920s as companies began to produce large machinery for the growing American economy. Over the past 100 years, industrial stocks have maintained their share of the market’s capitalization.

In reality, industrials have continued to grow over the past 100 years. IBM was considered an industrial company in the past but is now part of the Information Technology sector which in many years in the twenty-first century is the largest sector on the stock market.

Materials

The materials sector provides the inputs that other sectors use to generate their outputs. During most of the twentieth century, materials was one of the largest sectors in the economy as iron and steel, chemicals and mining provided the raw inputs that the country’s industries used to transform these raw materials into the automobiles and other goods that consumers wanted.

In the twenty-first century, materials have shrunk as intellectual property and services have grown in size and this will probably be the trend for the rest of the century. As the economy moves to rely more upon information technology and autonomous cars, materials will continue to provide the backbone of the American economy.

Consumer Staples

It is interesting to contrast consumer staples with consumer discretionary stocks. Consumer staples had almost no impact on the stock market until the 1890s because many people were farmers producing their own consumer staples, and the sector had not been taken over by large-scale firms providing consumer goods to millions of individuals employed in other industries.

Today, almost all food and beverages are produced by large conglomerates and represent a fairly fixed proportion of total output. The role of consumer staples is unlikely to change in the twenty-first century for a good reason, they are staples and as people grow richer, staples represent a shrinking share of total expenditures. This trend is unlikely to change.

Energy

Energy has been one of the most volatile sectors in the American stock market, dominating it when energy supplies are short and the price of energy shoots up, shrinking when energy prices collapse due to oversupply.

Until the 1860s, coal was the primary source of energy for the country. The Delaware and Hudson canal was built to transport coal from Pennsylvania to New York City and the rest of the country. But the real growth in the energy sector came with the discovery of oil in Pennsylvania and the hundreds of companies that emerged. Of these companies, Standard Oil became the largest of the group and by 1890, Standard Oil was the largest company in the world. Despite being broken up in 1913 and evolving to become ExxonMobil, Standard Oil remains one of the largest companies in the world.

Throughout the twentieth century, energy was one of the largest sectors in the economy, eclipsing railroads and finance by the 1920s. The only time period when energy lost its prominence in the stock market was in the 1990s when the price of oil collapsed in real terms to its pre-OPEC price, but as the Chinese economy grew and the price of oil increased to over $100 a barrel, ExxonMobil once again became the largest company in the world.

With the collapse of the price of oil after the Great Recession, the growth of fracking and the prospect of cleaner energy in the future, energy’s share of the American stock market has shrunk, but there is little reason to believe it won’t be the most volatile sector of the twenty-first century.

Communications

As a sector, communications is a recent addition. Until recently, media were part of the consumer discretionary sector, but with the ability to stream virtually any media in to your house, communications and entertainment have merged into a single sector.

to your house, communications and entertainment have merged into a single sector.

Communications as a separate sector in the American stock market was born in the 1860s when cables were laid across the oceans, telegraphs stretched across the country and railroads enabled express services to reach every part of the country. Telephones replaced the express services by the 1920s.

The communications sector has grown over the past 150 years because the price of communications has fallen dramatically. Increased demand has offset the fall in price. I can remember as a child waiting until 5pm or 11pm to make a phone call and take advantage of the lower phone rates that prevailed for long-distance phone calls in the off hours. Now it makes no difference what time you call or whether you make a local call or a long-distance call.

AT&T was the largest company in the United States between the 1920s and 1960s, and even though AT&T no longer holds that title, other companies provide communications that we didn’t even dream of 100 years ago. And who knows what will be available by the end of this century?

GFD has recalculated its indices to include all communications companies, not just telecommunications, in this sector from the 1860s to the 2010s. As can be seen, communications’ share of the stock market has grown continuously over the past 150 years, transforming itself as communication costs have declined. This trend will continue for decades to come.

Information Technology

Two sectors were born in the twentieth century, information technology and health care, and both of them have steadily grown in size. Of course, information technology was originally part of the industrial sector, but as computers have gradually taken over the economy, they have become their own sector because information technology has largely driven the growth in the stock market over the past few decades.

What really drove the growth of information technology was transistors and semiconductors which enabled information to be transmitted, calculated and stored in ways humans could not do by themselves. The S&P 500 and the whole stock market would not exist as it does today were it not for information technology. Stock trades take nanoseconds, not hours or days.

As new technologies are inevitably born in the decades to come, information technology will grow until the physical limits of information technology are reached. When that will occur remains to be seen.

Health Care

The final sector of the twelve is health care which will continues to grow in size because everybody dies. The only question is when. The older people get, the more expensive it is to keep them from dying and with health care now approaching 20% of GDP and the government funding the prolongation of life for an aging population, health care will slowly squeeze out the other sectors.

In the 1920s, there were drug companies, then there were health care suppliers, then hospitals, and now biotechnology. Pharmaceutical companies produce drugs that cost over $100,000 per year to delay the inevitable. Government and everyone else wants to control health care costs, but the Iron Law of Health Care is the closer you are to death, the more it costs to keep you from dying, but in the end, everyone dies. So health care as a sector will inevitably grow.

Conclusion

What will this stacked chart look like over the rest of the century? Which sectors will grow and which will shrink? What new sectors will come into existence, broken off from other sectors to reflect the dynamic changes in the economy?

When The Course of the Exchange introduced the concept of stock market sectors in 1811, they little realized how much sectors would change, but the number of sectors has barely changed, only the classification system has.

There is no reason why the twenty-first century shouldn’t endure as much change as the twentieth century did and no one can even predict what sectors will dominate the stock market by the end of the century. Who would have guessed that the largest sector of the nineteenth century, transports, would lose its classification as a sector by the twenty-first century?

The global economy will evolve over time and the sector map will change in ways no one can predict. Stay tuned.

Global Financial Data is completing its collection of data for the English stock market. The UK stocks database includes data on 25,000 companies from 1657 when the East India Company started trading in London to 1985.

GFD has written two other articles, “Four Centuries of Global Leadership” and “Two Centuries of American Leadership” which analyze how leadership in the global and American economies, with leadership defined as the largest listed company by market capitalization, has changed over the past several centuries. This article focuses on England.

London has a long history of creating companies that explored the world. As William R. Scott described in his three-volume set, The Constitution and Finance of English, Scottish and Irish Joint-Stock Companies to 1720, there were dozens of joint stock companies that were established in England before the South Sea Bubble in 1720 and the passage of the Bubble Act. The Virginia Company was established to create its colony in Jamestown. Dozens of other companies were founded, but ownership of the companies was so limited and concentrated that there is very little record of trades in their shares. When the Bubble Act was repealed in 1825, the number of companies in England exploded.

Although there is very little data on the trade in shares before 1694, we have been able to piece together some data on shares outstanding and trades from 1657 to 2017 to create 360 years of data on the largest companies in the United Kingdom every ten years from 1657 to 2017. GFD’s capitalization tool allows you to find out the size of the largest company and its competitors every year from the 1650s to the 1980s, if you want this information in detail.

What is fascinating about this history is not only what it tells us about capitalism, the financial market and technological change, but the politics of the market. Two companies that dominated the London Stock Exchange in the 1700s and 1800s were nationalized after World War II. The period between World War I and the Big Bang impacted the companies that were listed in London and their size, as did the merger and acquisition activity after the Big Bang. Politics, markets, technology and finance are all intertwined and developed over time in reaction to each other.

For a history of the London Stock Exchange, you need to look no further.

Global Financial Data is completing its collection of data for the English stock market. The UK stocks database includes data on 25,000 companies from 1657 when the East India Company started trading in London to 1985.

GFD has written two other articles, “Four Centuries of Global Leadership” and “Two Centuries of American Leadership” which analyze how leadership in the global and American economies, with leadership defined as the largest listed company by market capitalization, has changed over the past several centuries. This article focuses on England.

London has a long history of creating companies that explored the world. As William R. Scott described in his three-volume set, The Constitution and Finance of English, Scottish and Irish Joint-Stock Companies to 1720, there were dozens of joint stock companies that were established in England before the South Sea Bubble in 1720 and the passage of the Bubble Act. The Virginia Company was established to create its colony in Jamestown. Dozens of other companies were founded, but ownership of the companies was so limited and concentrated that there is very little record of trades in their shares. When the Bubble Act was repealed in 1825, the number of companies in England exploded.

Although there is very little data on the trade in shares before 1694, we have been able to piece together some data on shares outstanding and trades from 1657 to 2017 to create 360 years of data on the largest companies in the United Kingdom every ten years from 1657 to 2017. GFD’s capitalization tool allows you to find out the size of the largest company and its competitors every year from the 1650s to the 1980s, if you want this information in detail.

What is fascinating about this history is not only what it tells us about capitalism, the financial market and technological change, but the politics of the market. Two companies that dominated the London Stock Exchange in the 1700s and 1800s were nationalized after World War II. The period between World War I and the Big Bang impacted the companies that were listed in London and their size, as did the merger and acquisition activity after the Big Bang. Politics, markets, technology and finance are all intertwined and developed over time in reaction to each other.

For a history of the London Stock Exchange, you need to look no further.

East India Company.

In some ways, the largest company in England up until the 1720s wasn’t really an English company, but a company dedicated to foreign trade in India and the Far East. Actually, there were three companies, the East India Company, the New East India Company and the South Sea Company that dominated both foreign trade and the stock market in England until 1720. The British East India Company was actually established in 1600, a year before its Dutch cousin, but the Dutch East India Company was more successful than its English counterpart in the 1600s, taking over Indonesia and defeating the British East India Company in open battle to maintain its control over the Far East. Nevertheless, the British East India Company was successful enough that other private firms wanted a cut of the action. In 1694, the East India Co. lost its British monopoly over trade with India and in 1698 a new company, the English Company Trading to the East Indies was established to compete with the Governor and Company of Merchants trading with the East Indies. But competition meant fewer profits, and in 1708, the two companies merged into the United Company of Merchants of England trading to the East Indies after providing £3.2 million to the British government for the exclusive right to trade in India and the Far East. Those were the good old days when companies paid for their monopoly directly. As the table at the end of the article reveals, the original East India Company was the largest corporation in England in the 1600s. The New East India Company gained that prominence in 1698 and remained the largest company until 1708 when the conjoined company took over from its two predecessors. 1720 was the year of the South Sea Bubble when England followed in France’s footsteps and got holders of the bountiful British government debt to convert their bonds into equity in the South Sea Co. in the hopes of making a fortune. In 1720, there were 100,000 shares of South Sea stock outstanding and when the company’s shares hit £1045 on June 29, 1720, the market cap of the company was over £100 million. No other English company reached the £100 million mark for the next 200 years when Shell Transport and Trading broke through the £100 million barrier. Even at this summit, the South Sea Co. was half the size of the Compagnie des Indes which reached 210 Million Pounds in 1719 (6,302 Million Livres Tournois). This sum was slightly less than $1 billion, a size no company reached until Standard Oil became the first billion-dollar company in 1913.The Bank of England.

The South Sea Bubble brought an end to the dominance of foreign trading companies over the British stock market. From the 1720s to the 1860s, the Bank of England was not only the largest company in England, but in the world. Central banks dominated global stock markets in the 1800s. Whether it was England, France, the United States, Ireland or any other country, the largest company was usually the central bank. This remained true until the rise of the railroads during the 1800s. Central bank stocks were safe and provided a higher return than government bonds. Unlike the Bank of the United States, the Bank of England had a perpetual charter and faced virtually no competition. In fact, during the 1700s, the Bank of England was the stock market in England since it represented about 90% of the stock market capitalization of the British Isles. Between 1730 and 1860, depending upon market conditions, the Bank of England ranged in size from £12 million to £32 million ($60 million to $150 million). However, the Bank of England was only able to maintain its reign for so long. The railroad bubble of 1845 laid the foundations for the industry which would dominate the stock market during the rest of the nineteenth century.The London and Northwestern Railway

After the collapse of the railroad bubble of 1845, railroad companies in England merged with one another to control costs and raise prices. The largest railroad agglomeration was the London and North Western Railway which included the Grand Junction Railway, the London and Birmingham Railway and the Manchester and Birmingham Railway. The railroad continued to acquire other railroads in Lancashire and the Midlands making it the largest company in the world in 1865. The core of the line connected London to Birmingham, Liverpool and Manchester. At its peak, the company employed over 100,000 people. After 1900, the profitability of all the railroads in England declined. In 1923, the British government amalgamated all the British Railways into four main lines with the London and North Western Railway becoming a component of the London, Midland and Scottish railway. After World War II, the Bank of England and all the English railways were nationalized, and the two companies that had dominated the global economy from 1720 to 1900 became the property of the British government.Oil and Tobacco

In 1890, Standard Oil became the largest company in the world and since then, with the exception of the Japanese stock market bubble in 1989, the largest company in the world has always been an American company. Just as an oil company succeeded railroads as being the largest company in the United States, the same was true in England. Shell Transport and Trading took away the title from the London and Northwestern Railway in 1918.From World War II to the Big Bang

After World War II, the London stock market faced a new reality. The Bank of England, the railroads, and other key industries were nationalized by the Labour government, replacing the company’s shares with bonds. The Labour party felt they could manage the economy better than the private sector, but failed to prove it. As Atlee put it, “I cannot see why the motive of service to the community should not operate in peace as it did in war.” Obviously, Atlee did not understand human nature. Until Margaret Thatcher was elected in the 1980s, the British stock market faced battles between the Labour and Conservative governments with Labour governments nationalizing and Conservative governments privatizing. Labour often treated the stock market as an evil competitor, not as an engine for economic growth. If Labour could have closed down the stock exchange, they probably would have. The fear of government intervention and nationalization kept stock prices low during most of the 1950s and 1960s. Nevertheless, there were a few large companies that dominated the British market after the war. Notably, the dominant companies were international corporations, not purely British firms since many of the domestic companies were either nationalized or under threat of nationalization. Consequently, Shell Transport and British Petroleum were the largest companies on the London Stock Exchange between 1951 and 1959, handing off the title to each other over the years. Imperial Chemical took the top spot in 1960 and 1961 and Shell Transport took back its leadership in 1962. With the exception of 1966 when British Petroleum was the largest company, Shell held the title until 1985. The only dent in its rule was 1982 when General Electric plc was briefly the largest company in Britain.After the Big Bang

Margaret Thatcher wanted to bring free markets back to the United Kingdom. From July 31, 1914 when the London Stock Exchange closed because of World War I until October 27, 1986 when the Big Bang was launched, the London Stock Exchange operated under a set of restrictions which kept it from dominating the global economy the way London had before World War I. During World War I, Britain restricted new companies from listing in London, and the country went from being a net creditor to being a net debtor. The government directed capital toward its debt which grew to twice the size of GDP by the end of World War II. Exchange controls were in place until the 1970s and the London Stock Exchange lacked the freedom to operate as an open capital market the way it had before World War I. The goal of the Big Bang was to bring capitalism back to the United Kingdom in a big way by deregulating the market and allowing anyone to trade in a free market, not just the members of the old boy networks of brokers and jobbers that dominated London’s open outcry market. Computers replaced open outcry and foreign firms were free to buy up English firms and compete in an open market. The Big Bang was a huge success and London soon became the European center for financial markets. Denationalization also impacted London, creating new firms and new technologies. With the deregulation of telecommunications, the 1990s were dominated by British Telecommunications (BT Group plc) and Vodaphone. British Telecommunications was privatized in 1984 and quickly became one of the largest companies in the UK. Racal Telecom was spun off from Racal Electronics plc in 1991 and was renamed Vodaphone Group. After Vodaphone acquired Airtouch Communications and became Vodaphone Airtouch, it became the largest UK listed company in London, larger than BP Amoco or GlaxoSmithKline. In 2000, the top three companies were all conglomerates. Vodaphone had acquired Airtouch, British Petroleum had acquired Amoco (formerly Standard Oil of Indiana) and SmithKline Beecham had merged with Glaxo. Global capitalism was back. Just as ExxonMobil, formerly Standard Oil, took back the top spot in the United States in the 2000s, British Petroleum (BP plc) and Royal Dutch Shell (Shell Transport and Royal Dutch were unified into a single Netherlands based and British incorporated company in 2005) have dominated the London Stock Exchange in the 2000s and 2010s. As a result of the Big Bang, finance companies grew in size as well. HSBC Holdings (the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank) was the largest UK-listed company in London in 2015. In 2017, however, Royal Dutch Shell was the largest company listed on the London Stock Exchange.After Brexit?

The London Stock Exchange is the third largest stock exchange in the world by capitalization, falling behind the NYSE and NASDAQ. The London Stock Exchange will probably never regain its title as the largest stock exchange in the world, which it held in the 1700s and 1800s, but now even its role as the largest stock exchange in Europe is in question. How Brexit will impact the London Stock Exchange is an open question. Will European companies continue to trade in London or will Euronext take away London’s role as the central stock exchange for Europe? It is hard to believe that Britain could give up such a prize, but it has happened before. Politics determined the fate of the London Stock Exchange in the 70 years between World War I and the Big Bang in 1986. Will the London Stock Exchange face another 70 years of domestic politics determining its fate? With computers taking over trading, the London Stock Exchange probably won’t even exist in 70 years, but only time will tell. 350 Years of English Leadership| Year | Company | Market Cap in GBP |

|---|---|---|

| 1657 | East India Company | 0.756 |

| 1670 | East India Company | 0.84 |

| 1680 | East India Company | 2.06 |

| 1690 | East India Compay | 2.27 |

| 1700 | New East India Company | 4.33 |

| 1710 | East India Company | 3.78 |

| 1720 | South Sea Co. | 22.00 |

| 1730 | Bank of England Stock | 14.54 |

| 1740 | Bank of England Stock | 14.01 |

| 1750 | Bank of England Stock | 15.95 |

| 1760 | Bank of England Stock | 12.48 |

| 1770 | Bank of England Stock | 15.40 |

| 1780 | Bank of England Stock | 12.71 |

| 1790 | Bank of England Stock | 21.78 |

| 1800 | Bank of England Stock | 18.79 |

| 1810 | Bank of England Stock | 28.40 |

| 1820 | Bank of England Stock | 32.46 |

| 1830 | Bank of England Stock | 28.97 |

| 1840 | Bank of England Stock | 22.92 |

| 1850 | Bank of England Stock | 31.00 |

| 1860 | Bank of England Stock | 33.91 |

| 1870 | London & North-Western Railway | 38.40 |

| 1880 | London & North-Western Railway | 53.66 |

| 1890 | London & North-Western Railway | 67.74 |

| 1900 | London & North-Western Railway | 76.26 |

| 1910 | London & North-Western Railway | 59.19 |

| 1920 | Shell Transport and Trading Co. | 114.43 |

| 1930 | Imperial Tobacco Co. (Imperial Group plc) | 177.25 |

| 1940 | Imperial Tobacco Co. (Imperial Group plc) | 188.99 |

| 1950 | Imperial Tobacco Co. (Imperial Group plc) | 197.21 |

| 1960 | Imperial Chemical Industries Ltd. | 844.38 |

| 1970 | British Petroleum (BP plc) | 1,596.78 |

| 1980 | British Petroleum (BP plc) | 6,637.91 |

| 1990 | BT Group plc (British Telecommunications) | 69,391.95 |

| 2000 | Vodaphone Group plc | 158,679.67 |

| 2005 | British Petroleum (BP plc) | 128,497.27 |

| 2010 | Royal Dutch Shell plc | 133,713.21 |

| 2015 | HSBC Holdings (Hong Kong & Shanghai Bank) | 103,344.96 |

| 2017 | Royal Dutch Shell plc | 207,964.51 |

The article Four Centuries of Global Leadership tracked the largest company in the world from 1602 to 2018. This article focuses on the United States, detailing how leadership, in terms of the company with the largest market cap, has changed over the past two centuries.

The table which accompanies this article provides a unique history of the United States stock market. We have calculated the number companies in the market at five-year intervals, the value of the capitalization of the United States stock market and what was the largest company in the U.S. stock market. We have data for every year from 1782 to 2018, but we thought five-year intervals would be sufficient to show the general trends.

The data covers every stock exchange and over-the-counter stock for which GFD was able to collect data. GFD is still adding data to the United States stock database so the totals a year from now will be even larger than they are today. Using this table, you can break the history of the U.S. stock market down into several eras.

The article Four Centuries of Global Leadership tracked the largest company in the world from 1602 to 2018. This article focuses on the United States, detailing how leadership, in terms of the company with the largest market cap, has changed over the past two centuries.

The table which accompanies this article provides a unique history of the United States stock market. We have calculated the number companies in the market at five-year intervals, the value of the capitalization of the United States stock market and what was the largest company in the U.S. stock market. We have data for every year from 1782 to 2018, but we thought five-year intervals would be sufficient to show the general trends.

The data covers every stock exchange and over-the-counter stock for which GFD was able to collect data. GFD is still adding data to the United States stock database so the totals a year from now will be even larger than they are today. Using this table, you can break the history of the U.S. stock market down into several eras.

The Era of the First and Second Bank of the United States

The Bank of North America was established in the United States in 1781 by Robert Morris with $1 million in capital. The first Bank of the United States (see the blog, “Alexander Hamilton and the First Bank of the United States”) was established in 1791 by Alexander Hamilton with a capital of $10 million, $2 million of which was subscribed to by the United States government. The bank failed to gain enough votes for its renewal in 1811 and was finally liquidated in 1815. A second Bank of the United States was established in 1816 with $35 million in capital. Andrew Jackson fought the renewal of the second Bank’s charter in 1836 and the bank died, leaving the United States with no central bank until 1913 when the Federal Reserve was established. As you can see by the numbers, when the first Bank was established in 1791, the Bank was the stock market, representing 86% of the capitalization of the four firms that existed. Over the next 20 years, the number of companies listed in the U.S. grew from 4 to 79 and the first Bank’s share of total market cap fell from 86% to 13%. The bank’s charter ended in 1811, but it took four years to liquidate the bank. The second Bank of the United States (see the blog, “The Bank War”) was established in 1816 with $35 million in capital, and in 1820 it represented 39% of the total capitalization of the United States stock market, but over time, its share declined as well, to 15% the year before its charter expired in 1836 when Congress failed to override President Jackson’s veto. During its existence, however, the number of listed companies in the U.S. grew from 95 in 1820 to 299 in 1835 and the capitalization of the U.S. stock market grew to over one-quarter of a billion dollars.The Era of Chicago Railroads

The Bank of the United States collapsed soon after 1840, ultimately going bankrupt, and in 1845, the transportation era began. Railroads were built in every state, and in 1845, three railroads were neck and neck for the top position, the Vermont Central, the South Carolina Railroad Co. and the Western Railroad Co. of Massachusetts, each with around $4.5 million in market cap. In 1850, the Delaware and Hudson Canal, which stretched from the upper portion of the Hudson River in New York to the coal valleys of Pennsylvania was the largest company in the United States. The canal transported anthracite coal from northeastern Pennsylvania through 108 locks to the Hudson whence the coal could be brought to New York City and the rest of the country. Over the next three decades, the largest company in the United States was a railroad that connected Chicago to the rest of the country. Leadership passed between several different railroads, including the New York Central which went from New York City to Chicago, and three Chicago-based railroads, the “Rock Island” which served the areas to the west of the Mississippi, the Illinois Central, which served the Mississippi Valley from Chicago to New Orleans and the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy, which connected Chicago to the grain growing states of the Midwest. There is no reason why the second-half of the nineteenth century shouldn’t be called the Era of Chicago Railroads. The windy city was at the heart of the nation and connected all points to the west and south of Chicago to the east where the nation’s goods were sold. In fact, the Northern Pacific stock corner (see the article “Northern Pacific – The Greatest Stock Squeeze in History”) occurred because two railroads which were not connected to Chicago battled over controlling a railroad which went into Chicago. However, by the time the Columbian Exposition took place in Chicago in 1893, the railroads had lost their crown to a new sector of the economy: oil.The Era of Standard Oil

Standard Oil became not only the largest company in the United States, but the largest company in the world by 1900. Before 1900, the London & Northwestern Railway of the UK was the largest railroad and the largest company in the world, having succeeded the Bank of England in the 1860s. The London & Northwestern Railway employed over 100,000 people connecting London with Birmingham and the surrounding cities. The interesting fact about Standard Oil, however, was that even though it was the largest company in the world, it wasn’t listed on any exchange in the United States and was only traded over-the-counter! Until Standard Oil was broken up by the U.S. government in 1913, it remained the largest company in the United States between 1888 and 1913. From 1890 until today, with the exception of the Japanese stock market bubble in 1989, the largest company in the world has always been an American company. After Standard Oil was divided into 32 companies, it lost the blue ribbon for largest company to Penn Central, which connected New York City to Chicago. Standard Oil regained the crown in 1920 as the Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey and for several years in the 21st century, Standard Oil regained the title as ExxonMobil. It should be noted here that the largest company inevitably comes under the scrutiny of the government. Both the Bank of England and the London and Northwestern Railway were nationalized by the British government after World War II. Standard Oil was broken up in 1913 as was AT&T in 1983. IBM and Microsoft were both threatened to be broken up by the application of American Antitrust laws and the tech giants of 2018 are currently under the scrutiny of politicians in Washington.The Era of AT&T

Before the American government intervened, Ma Bell was the largest company in the world, keeping the title consistently from 1923 until 1965 except for 1927, 1928 and 1954 to 1956 when General Motors took the title away from AT&T. AT&T had a 40-year stretch in which it ruled the United States stock market as the largest and one of the safest stocks to invest in. One of the odd stories about AT&T is that in 1938, Dow Jones reorganized its indices, reducing the Utilities index from 20 stocks to 15 and restricting the index to electric utilities. Until then, the Dow Jones Utilities Index had included AT&T and Wells Fargo since telecommunications companies were considered utilities. AT&T was moved to the Dow Jones Industrials and IBM was removed from the index until 1979. If IBM had stayed in the index between 1938 and 1979 and AT&T had been left in the Utilities, the Dow Jones Industrials would be 22,000 points higher than it is today (see the blog “Dow Jones Industrial Average’s 22,000 Point Mistake”).The Era of IBM

In 1967, IBM became the largest company in the world, replacing AT&T. It held the top spot until 1989 when it was replaced by ExxonMobil (formerly Standard Oil of New Jersey). During that period of time AT&T was broken up into Ma Bell and the Baby Bells and IBM was under constant threat of being broken up by the United States government. But it wasn’t the government that was ultimately the downfall of IBM, it was the personal computer that replaced the mainframes and their huge computing power that created a new market IBM could not dominate. Nevertheless, IBM defined the go-go era of the 1960s and 1970s and gave notice that tech stocks were the dominant industry in the United States. Large companies could not operate without the use of computers, in fact, the stock market itself could not operate without computers. IBM computerized the stock market, made the daily calculation of the S&P 500 possible, enabled electronic orders to replace paper orders and brought the time of trades from minutes to nanoseconds.The Big Four

Although General Electric was the largest company in 1995, 2000 and 2005, there were actually three companies that traded the title between them between 1991 and 2011, General Electric, ExxonMobil and Microsoft. Each of them was the largest in their sector and according to the economic conditions of the year, one of those three was on top with the other two close behind. General Electric wasn’t just an electricity and manufacturing company anymore, but was a finance company that provided funding to corporations and consumers. As the finance sector began to take over the stock market in the 2000s, this helped General Electric to stay on top. Microsoft was the reason for IBM’s downfall since it played a central role in the replacement of the mainframe with the personal computer, but just like IBM, Microsoft felt the ire of the government when the company was sued under the antitrust laws and also came close to being broken up. ExxonMobil, the descendent of Standard Oil benefitted from the price of oil surpassing $100 a barrel to become the biggest company in the world between 2006 and 2011. But when the price of oil went down, so did ExxonMobil and with iTunes and the iPhone beginning to take over the world, Apple moved up to the top spot.Growth in the American Stock Market

In addition to keeping track of the largest company in the United States, the table also provides information on the size of the U.S. stock market, both in terms of the number of companies listed on U.S. exchanges and their total capitalization. All data are based upon companies included in the US Stocks Database and are available to subscribers. The number of companies grew from 1 in 1782 to 100 in 1823, to 500 in 1871, to 1000 in 1888 and 2,000 in 1895. The number of companies peaked at 9,850 in 1999 and has declined since then to around 5,400 in 2017. At this rate, one wonders whether there will even be 3,000 companies to put into the Russell 3000 in the near future. The total capitalization of the U.S. market has also grown dramatically, starting off at $1 million in 1782, reaching $100 million in 1823, and $1 billion in 1869. In 1898, the United States surpassed Great Britain as the country with the largest market cap in the world at over $6 billion. The total market cap reached $10 billion in 1901, $100 billion in 1950 and $1 trillion in 1971. Today the market cap exceeds $30 trillion.Conclusion

Who will be the biggest company five or ten years from now? A tech company like Apple, Alphabet, Facebook, Microsoft or Amazon? A former leader like ExxonMobil, a bank like JPMorgan Chase or a conglomerate like Berkshire Hathaway? Or some company we haven’t even heard about? Or will America cede the top spot to a Chinese company like Tencent or Alibaba? Only time will tell. Two Centuries of American Leadership| Year | Firm | Top Firm Market Cap | Companies Listed | Total US Market Cap | Average Firm Size | Top Firm Share Total Market Cap |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1782 | Bank of North America | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 1791 | Bank of the United States (First) | 14.80 | 4 | 17.18 | 4.30 | 86.15 |

| 1795 | Bank of the United States (First) | 13.00 | 9 | 26.93 | 2.99 | 48.28 |

| 1800 | Bank of the United States (First) | 13.75 | 13 | 28.31 | 2.18 | 48.57 |

| 1805 | Bank of the United States (First) | 13.00 | 43 | 44.70 | 1.04 | 29.08 |

| 1810 | Bank of the United States (First) | 10.90 | 68 | 61.51 | 0.90 | 17.72 |

| 1815 | Bank of the United States (First) | 9.00 | 79 | 68.64 | 0.87 | 13.11 |

| 1820 | Bank of the United States (Second) | 36.58 | 95 | 94.63 | 1.00 | 38.65 |

| 1825 | Bank of the United States (Second) | 42.35 | 161 | 136.13 | 0.85 | 31.11 |

| 1830 | Bank of the United States (Second) | 45.50 | 174 | 136.13 | 0.86 | 30.29 |

| 1835 | Bank of the United States (Second) | 39.59 | 299 | 262.42 | 0.88 | 15.09 |

| 1840 | Bank of the United States (Second) | 22.88 | 337 | 254.25 | 0.75 | 9.00 |

| 1845 | Vermont Central Railroad Co. | 4.60 | 310 | 234.48 | 0.76 | 1.96 |

| 1850 | Champlain National Corp. (Delaware & Hudson Canal) | 7.92 | 365 | 346.48 | 0.95 | 2.29 |

| 1855 | Chicago Rock Island & Pacific Railway Co. (1847) | 26.70 | 422 | 464.45 | 1.10 | 5.75 |

| 1860 | New York Central Railroad (1853) | 18.06 | 405 | 463.20 | 1.14 | 3.90 |

| 1865 | Illinois Central Railroad Co. | 28.15 | 420 | 796.16 | 1.90 | 3.54 |

| 1870 | New York Central Railroad (1869) | 78.69 | 444 | 1.105.71 | 2.49 | 7.12 |

| 1875 | New York Central Railroad (1869) | 93.56 | 612 | 1,528.32 | 2.50 | 6.12 |

| 1880 | New York Central Railroad (1869) | 138.09 | 886 | 2,590.69 | 2.92 | 5.33 |

| 1885 | Chicago Burlington and Quincy Railroad Co. | 105.12 | 946 | 2,904.07 | 3.07 | 3.62 |

| 1890 | Standard Oil of New Jersey (ExxonMobil) | 149.78 | 1,016 | 3,477.83 | 3.42 | 4.31 |

| 1895 | Standard Oil of New Jersey (ExxonMobil) | 191.10 | 2,560 | 4,760.85 | 2.32 | 4.01 |

| 1900 | Standard Oil of New Jersey (ExxonMobil) | 803.00 | 2,199 | 8,899.22 | 4.05 | 9.02 |

| 1905 | Standard Oil of New Jersey (ExxonMobil) | 687.88 | 2,470 | 13,929.24 | 5.64 | 4.94 |

| 1910 | Standard Oil of New Jersey (ExxonMobil) | 608.71 | 2,594 | 16,046.06 | 6.19 | 3.79 |

| 1915 | Penn Central Corp. ($50 Par) | 591.63 | 2,560 | 20,459.19 | 8.01 | 2.89 |

| 1920 | Standard Oil of New Jersey (ExxonMobil) | 613.63 | 2,649 | 21,873.22 | 8.26 | 2.81 |

| 1925 | American Telephone & Telegraph Co. | 1,319.00 | 3,317 | 47,567.64 | 14.34 | 2.77 |

| 1930 | American Telephone & Telegraph Co. | 3,152.55 | 3,041 | 63,251.49 | 20.80 | 4.98 |

| 1935 | American Telephone & Telegraph Co. | 2,802.11 | 2,229 | 51,644.92 | 23.17 | 5.43 |

| 1940 | American Telephone & Telegraph Co. | 3,143.24 | 2,279 | 44,966.63 | 19.73 | 6.97 |

| 1945 | American Telephone & Telegraph Co. | 3,851.71 | 2,189 | 75,945.28 | 34.69 | 5.07 |

| 1950 | American Telephone & Telegraph Co. | 4,320.87 | 2,315 | 111,597.30 | 48.21 | 3.87 |

| 1955 | General Motors Corp. (Old) | 12,768.78 | 2,205 | 251,419.80 | 114.02 | 5.08 |

| 1960 | American Telephone & Telegraph Co. | 23,944.37 | 2,281 | 380,328.20 | 166.74 | 6.30 |

| 1965 | American Telephone & Telegraph Co. | 32,072.60 | 2,932 | 607,877.10 | 207.33 | 5.28 |

| 1970 | International Business Machines Corp. | 36,218.42 | 4,031 | 694,247.80 | 172.23 | 5.22 |

| 1975 | International Business Machines Corp. | 33,378.94 | 5,270 | 736,652.30 | 139.78 | 4.53 |

| 1980 | International Business Machines Corp. | 39,606.90 | 5,191 | 1,337,999.00 | 257.75 | 2.96 |

| 1985 | International Business Machines Corp. | 95,299.74 | 6,379 | 2,222,049.00 | 348.34 | 4.29 |

| 1990 | International Business Machines Corp. | 64,528.99 | 6,680 | 2,911,041.00 | 435.78 | 2.22 |

| 1995 | General Electric Co. | 120,259.80 | 8,030 | 6,546,687.00 | 815.28 | 1.84 |

| 2000 | General Electric Co. | 475,003.24 | 7,946 | 15,181,594.00 | 1,910.60 | 3.13 |

| 2005 | General Electric Co. | 367,473.66 | 6,820 | 16,393,740.00 | 2,403.77 | 2.24 |

| 2010 | ExxonMobil Corp. (Standard Oil of New Jersey) | 368,711.99 | 7,835 | 18,368,258.00 | 2,344.39 | 2.01 |

| 2015 | Apple Inc. | 586,859.24 | 6,269 | 26,524,419.00 | 4,231.04 | 2.21 |

| 2017 | Apple Inc. | 874,111.87 | 5,224 | 33,541,682.00 | 6,420.69 | 2.61 |