The equity-risk premium (ERP) is one of the most important variables in finance. In theory, riskier stocks should provide a higher return than risk-free government bonds, but unfortunately, this is not always true. Different factors drive return to stocks and bonds. Bond returns are driven by inflation; stock returns are driven by corporate cash flows. The two will vary independently of one another. It is not risk alone that determines the equity-risk premium. Any review of the equity-risk premium shows that its value is not constant, and even if you average returns over 10 or 20 years, the premium can vary dramatically. Using GFD’s data, analysis of the evolution of the equity-risk premium over the past 300 years is possible. . Information on the Equity Risk Premium in 20 countries can be found in the GFD Guide to Global Stock Markets.

The US Takes a Wild Ride on the ERP

Figure 1. 10-year Returns to Stocks and Bonds in the United States, 1792 to 2023

The 10-year return to stocks and bonds in the United States is illustrated in Figure 1. The black line represents the return to stocks, and the green line, the return to bonds. The 10-year return to stocks between from 2012 to 2022 was 12.45%. An investment in bonds returned 0.20% during the same time period and the equity premium would have been 12.25%.

As Figure 1 illustrates, the return to stocks is more volatile than the return to bonds. The 10-year return to stocks fell from 19.87% in 1999 to -2.34% in 2009. During that same period the return to government bonds fell from 7.98% to 6.40%. The return to stocks greatly influences the equity-risk premium as can be seen by the volatile returns in Figure 1 relative to the slower change in the return to bonds.

There is a strong correlation between the current yield on government bonds and the total return over the subsequent 10 years. Few people realize that you can use the yield to predict the future return on government bonds. The market would predict that investors will receive about a 4% return on government bonds between 2023 and 2033.

The black line shows the yield in 2022 and the green line shows the return to bonds between 2012 and 2022. As bond yields declined between 1981 and 2019, fixed-income investors received capital gains that largely offset the decline in bond yields. Although yields fluctuate up and down from year to year, bond yields can trend up or down for decades. Bond yields generally declined from 1920 until 1945, rose until 1981 and declined until 2021. They have increased from a low of 0.5% in 2020 to over 4% now.

Figure 2. United States 10-year Government Bond Yield and Returns, 1920 to 2023

Now Trending 100 Years

Unfortunately, there is no similar indicator to predict future returns to stocks. Dividend yields don’t change very much, but the price of stocks do. Nevertheless, using a 10-year average return shows that the return to stocks does trend over time; however, the trends are shorter than the trends in risk-free bonds. During the past 100 years, 10-year peaks in the return to stocks occurred in 1928, 1958 and 1999. Peaks in the return to bonds occurred in 1930 and 1991. 10-year bottoms occurred in stocks in 1938, 1974 and 2009 and in bonds in 1959 and 2018. There have basically been three market cycles in stocks over the past 100 years and two in bonds. Currently, the return to stocks is in an uptrend that began in 2009 while bonds are trading in a downtrend that began in 1991. Both of these trends should reverse soon, but the 10-year ERP will probably remain positive for the rest of the decade because it will take time for these two trends to once again converge.

Figure 3. United States 10-year Equity Risk Premium, 1792 to 2019

The 10-year average of the equity risk premium in the United States over the past 200 years is illustrated in Figure 3. Volatility in the equity premium is driven more by changes in the return to stocks than changes in the return to bonds.

If you compare the Equity Risk Premium in the 1800s with the 1900s you will see a dramatic difference in the ERP. During the 1800s, there were more frequent and longer periods when the ERP was negative than in the 1900s. In fact, the ERP was negative the majority of the time before the 1850s when banks and insurance companies dominated American stock markets.

Government bonds were safer than equities during the first half of the nineteenth century. When railroads exploded onto the scene in the 1840s and represented the majority of stock market capitalization for the rest of the century, this changed. After the civil war, bond yields declined, and stock returns rose returning the ERP to positive territory for most of the second half of the 1800s.

During the 1900s, it was only during periods of recession that the ERP turned negative, mainly due to the poor performance of stocks. This occurred in the early 1920s in the post-World War I recession, during the Great Depression in the 1930s, during the energy crisis of the 1970s and during the Great Financial Crisis in the 2000s when the stock market twice declined over 50%.

Although stocks are riskier than bonds, there are 17 periods during the past 100 years when the equity-risk premium was negative meaning that bonds outperformed stocks over a 10-year period. The equity-risk premium has been negative in 59 of the past 221 years meaning that bonds outperformed stocks 27% of the time. The worst return came in the decade between 1999 and 2009 when bonds beat stocks by 8.22% per annum. The highest equity premium was in 1959 when stocks beat bonds by 18.17%.

The UK Equity Risk Premium: The Effect of War, Peace and Bubbles

Figure 4 shows the equity-risk premium in the United Kingdom since 1700. Several things are immediately discernable. There were four periods in the 1700s when bonds outperformed stocks, the most dramatic period being between 1710 and 1720 (-7.62%) when the South Sea Bubble struck financial markets. By contrast, the highest ERP was in the 1760s when the United Kingdom was at peace, interest rates declined, and stock returns rose.

The ERP was mostly positive for the 150 years between the 1760s and 1920s with the exception of the decade that followed the end of the Napoleonic Wars. The yield on bonds remained high while the return to stocks declined. The 1800s were a century of peace in which money was freed up from government bonds to invest in railroads and other industries. By consistently outperforming bonds, equities attracted money away from British consols. There was a crowding-in effect as capital flowed to industry in the United Kingdom and the rest of the world. The result was steady growth as the global economy developed.

Figure 4. United Kingdom 10-year Equity Risk Premium, 1700 to 2023

The twentieth century was a roller coaster ride compared to the previous two centuries. The equity premium plunged from 4.66% in 1928 to -5.95% in 1938, rose to 16.33% in 1959, fell to -0.12% in 1982, shot up to 12.94% in 1985 and declined to -4.91% in 2008. By comparison, the 1800s had few dramatic swings in the equity-risk premium. The equity-risk premium rose to only 3% in the 1800s but ranged between 13% and 16.34% between 1949 and 1953.

Although the charts for the United Kingdom and the United States look quite different in the 1800s, they are very similar in the 1900s. Again, it is the post-World War I era of the 1920s when the ERP was negative in both countries. Rising bond yields during the post-war inflation, and thus lower bond prices, and declining returns to equities pushed the ERP into negative territory for ten years. This is a reminder that there can be long periods of time when stocks consistently underperform bonds. A positive ERP is not a given. The other primary period when the ERP was negative was the 2000s when bond yields were high, and the stock market faced two dramatic declines in 2000 and 2008 during the Great Financial Crisis.

The similarity in results for the United States and the United Kingdom since 1914 is striking. If we were to chart the ERP for other countries during the past 100 years, we would get similar results. The minimum and maximum dates of the ERP are similar. The ERP is driven by changes in equity returns more than bond returns and equity markets in the United States and the United Kingdom rose and fell at similar points in time. Obviously, financial markets are more integrated across international borders today than they were 200 years ago. Integration will only increase in the future.

Around the World with the ERP

Finally, we wanted to examine the ERP for the entire world. All values for stocks and bonds are converted to US Dollars. The United States and the United Kingdom have represented over half of global market capitalization during the past 300 years, so the results for the global ERP are similar to the data for the UK and USA. There is no world government bond, so we use the US government 10-year bond as a proxy for the risk-free bond. As Figure 5 shows, there are very few years in which the ERP was negative. The main periods were in the 1720s after the South Sea Bubble, during the Napoleonic Wars, during the 1820s, during the 1920s and around 2010. The highest returns came in the 1920s, 1940s and 1950s. The 2010s also provided one of the highest ERPs in history, though more because of low bond yields than high stock returns. Stocks do, on average, outperform bonds.

Figure 5. World 10-year Equity Risk Premium, 1710 to 2023

Winners and Losers

Table 1 looks at the ERP by decade in the United States, the United Kingdom, and the world over the past 200 years. The decades when the ERP was negative are marked in red. Over time, returns in the United States, the United Kingdom and the world have become more coordinated as financial markets have become more integrated. While decade returns differed in the 1800s, they lined up much better in the 1900s and 2000s. The 1930s and 2000s were the two decades when the ERP was negative in both countries and in the world. This shows that global integration of stock and bond markets has increased over time.

|

Decade |

United States |

United Kingdom |

World |

|

1789-1799 |

0.98 |

1.94 |

5.26 |

|

1799-1809 |

-0.68 |

2.82 |

-0.24 |

|

1809-1819 |

-4.54 |

0.45 |

-0.44 |

|

1819-1829 |

0.11 |

-3.16 |

-3.43 |

|

1829-1839 |

2.75 |

0.26 |

3.24 |

|

1839-1849 |

-2.14 |

-1.26 |

-0.04 |

|

1849-1859 |

1.01 |

3.65 |

2.11 |

|

1859-1869 |

4.59 |

2.77 |

3.39 |

|

1869-1879 |

2.62 |

3.52 |

2.99 |

|

1879-1889 |

0.42 |

3.22 |

2.46 |

|

1889-1899 |

5.68 |

2.29 |

3.09 |

|

1899-1909 |

8.88 |

1.47 |

4.09 |

|

1909-1919 |

5.44 |

8.66 |

8.45 |

|

1919-1929 |

6.81 |

0.18 |

6.23 |

|

1929-1939 |

-2.55 |

-3 |

-2.25 |

|

1939-1949 |

6.1 |

4.43 |

6.64 |

|

1949-1959 |

18.16 |

17.89 |

17.73 |

|

1959-1969 |

4.91 |

7.98 |

6.67 |

|

1969-1979 |

0.65 |

1.04 |

1.64 |

|

1979-1989 |

3.79 |

8.2 |

6.74 |

|

1989-1999 |

11.01 |

3.19 |

3.58 |

|

1999-2009 |

-8.21 |

-4.84 |

-5.93 |

|

2009-2019 |

8.91 |

2.75 |

5.83 |

|

2019-2022 |

12.23 |

11.3 |

12.25 |

Table 1. Equity Risk Premium in the United States, the United Kingdom and the World by Decade

Life in the 2020s

Current trends support the continuance of the equity premium remaining high in the United States, the United Kingdom, and the world during the rest of the decade. Data indicates that stocks beat bonds 80% of the time, and bonds outperform 20% of the time.

Rising bond yields in 2021 and 2022 caused losses to bonds increasing the Equity Risk Premium. The losses in 2021 and 2022 will ensure that the Equity Risk Premium will remain positive for the rest of the decade. Returns to bonds are likely to be around 4% during the next few years. Therefore, the equity premium will remain primarily dependent upon the return to stocks.

Historically, the equity risk premium has averaged around 3% for the United States and the United Kingdom. With bonds yielding 4% in the US and the UK, it would be difficult to expect equity returns to be much greater than 7% over the next ten years. On the other hand, the return to equities in the United States has been around 10% during the past decade. Investors have gotten used to high returns, but they will probably have to adjust to receiving lower returns on stocks and higher returns on bonds during the rest of the decade.

I often crave donuts being the sugar lover that I am. And I am not alone here at Global Financial Data. On the way to the office there is a local Donut shop called Rose Donuts & Cafe, which has the best donuts as is depicted in Figure 1 — fluffy, fresh, overly large delights such as maple bars, cake donuts, sprinkles, chocolate glazed, old fashioned, Bavarian crème filled goodies, and cinnamon rolls so large you could quarter them and still be stuffed. So many flavors to choose from, French-croissants and fresh baked muffins.

Figure 1. Rose Donuts & Café, 624 Camino De Los Mares, San Clemente, CA 92673

So, I ask myself why is there still a Dunkin’ Donuts, across the street when Rose’s donuts taste so much better? I had to find out who owns the Dunkin chain because it must have some story behind it because they certainly don’t have good tasting donuts in my opinion. And quite a story there is.

Dunkin’ Donuts, Figure 2, as it is known today, was founded by William Rosenberg, a Jewish immigrant, who only completed the eighth grade. He was quickly forced to work at the age of 14 to help support his family when his father Nathan lost the family grocery store during the great depression and held many jobs during his teen years. After working for Western Union, as a full-time telegram delivery boy, Rosenberg began working for Simco, a company that distributed ice cream from refrigerated trucks. At Simco, he quickly rose through the company and by age 21, he was a manager supervising their production and manufacturing of nearly 100 trucks.

Figure 2. Example of Dunkin’ Donuts

Through his observation of human purchasing behavior over the course of his many jobs in the service industry, Rosenberg gained the knowledge necessary to start his own donut shop. However, Rosenberg did more than just that. He started an entire franchise and even adjusting for inflation – he did it with very little cash in 1940s.

After World War II, Rosenberg borrowed $1,000 and combined this with $1,500 (roughly $25,000 today) he had in war bonds to start his mobile catering service “Industrial Lunch Services” that delivered meals and offered coffee break services to factory workers outside of Boston, Massachusetts.

Rosenberg designed his own catering vehicle, as seen in Figure 3, that had custom-built stainless steel shelves that stocked snacks and sandwiches which were basically a prototype for the current mobile catering vans still used today. Rosenberg’s focus was on making the customer happy through options and choice as his trucks clearly displayed the items for customers to make their own selection. Shortly, thereafter, Rosenberg had over 200 catering trucks, 25 in-plant outlets and a vending operation that delivered food to factory workers. Through continued observation, while serving food at construction sites and factories, where that donuts and coffee were the top picks of the daily visitors who were often in a hurry, Rosenberg’s knowledge grew as he continued to study the human experience.

Figure 3. Industrial Lunch Services Catering Truck

Shortly thereafter, he decided to open a store that specialized in coffee and donuts after he determined that 40% of his revenues came from coffee and donuts and wanted to offer 52 varieties of donuts since traditional donut shops offered only five different varieties. On Memorial Day in 1948 in Quincy, Massachusetts, Rosenberg founded Open Kettle Donuts, changed its name to Kettle Donuts, and then to Dunkin’ Donuts in 1950.

Early on Rosenberg began laying an excellent foundation of marketing concepts for Dunkin’ Donuts beginning with an ideal name for his business combining the coffee and donuts theme from his previous personal experience. He laid the foundation for the brand even before it began through his keen sense of human need and Rosenberg coined the phrase “The Customer is Boss.” His initial brand foundation was off to a great start and within five years, others began expressing a franchise interest. Rosenberg continued to grow the franchise chain to 100 locations in 1963, when he turned the day to day operations over to his son.

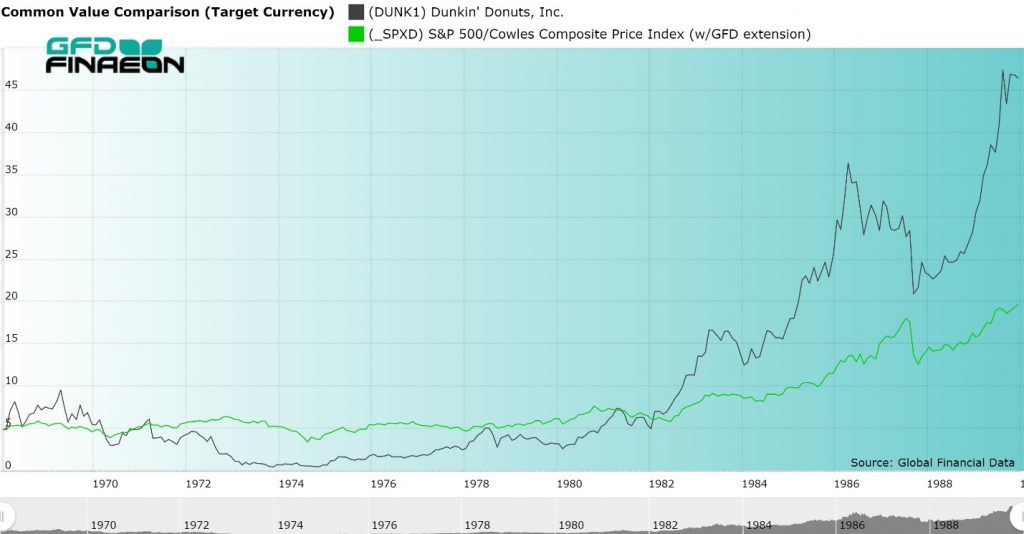

In 1990, with more 1000 stores, British beverage conglomerate, Allied Domecq purchased the thriving Dunkin’ Brands fast food restaurant chain. Figure 4 shows the performance of Dunkin’ Donuts between 1968 and 1990 when the company was bought out at $43.75 per share. The company underperformed the S&P 500 in the 1970s, but during the 1980s, it hit its stride and the stock price rose dramatically. The company had stock splits in 1981, 1983 and 1985. The company’s revenues more than doubled and the stock price rose over tenfold. You can see why Allied Domecq felt they had made a good investment. I have also included the fundamentals for your review. These can be seen in Figure 5.

Figure 4. Dunkin’ Donuts, Inc. vs. S&P 500, 1968 to 1990

FUNDAMENTALS OF DUNKIN’ DONUTS 1968-1989

| Date | Net Sales ($ Million) | Shareholder’s Equity | Price To Sales | Price To Cash Flow |

| 10/31/1968 | 14.352 | 5.1 | 6.28 | 81.67 |

| 10/31/1969 | 14.229 | 6.7 | 3.07 | 29.01 |

| 10/31/1970 | 17.578 | 8.2 | 1.77 | 17.50 |

| 10/31/1971 | 19.2024 | 9.3 | 1.33 | 24.55 |

| 10/31/1972 | 23.4498 | 12.3 | 0.64 | 12.97 |

| 10/31/1973 | 24.9546 | 10.5 | 0.15 | -2.40 |

| 10/31/1974 | 27.4 | 11.8 | 0.14 | 6.70 |

| 10/31/1975 | 34.5 | 13.3 | 0.29 | 12.03 |

| 10/31/1976 | 43.3 | 16.1 | 0.30 | 11.93 |

| 10/31/1977 | 51.8 | 18.9 | 0.38 | 14.93 |

| 10/31/1978 | 57.1 | 22.3 | 0.50 | 7.94 |

| 10/31/1979 | 63.2 | 23.5 | 0.37 | 5.75 |

| 10/31/1980 | 63.5 | 27.1 | 0.49 | 6.70 |

| 10/31/1981 | 66.331 | 27.148 | 1.64 | 4.92 |

| 10/31/1982 | 64.918 | 31.802 | 1.23 | 8.24 |

| 10/31/1983 | 71.318 | 38.104 | 1.51 | 9.90 |

| 10/31/1984 | 77.495 | 44.994 | 1.44 | 8.93 |

| 10/31/1985 | 85.45 | 53.028 | 1.92 | 11.40 |

| 10/31/1986 | 94.391 | 62.158 | 2.31 | 13.22 |

| 10/31/1987 | 101.037 | 72.603 | 1.65 | 9.91 |

| 10/31/1988 | 102.714 | 68.219 | 1.68 | 8.65 |

| 10/31/1989 | 109.336 | 72.653 | 2.46 | 12.48 |

|

Figure 5. Dunkin’ Donuts Fundamentals, 1968 to 1989 |

Fifteen years later, in July 2005, Allied Domecq was acquired by their parent company, Pernod Ricard SA. Pernod knew quickly that they needed to alleviate debt, so the French beverage company began searching for a buyer for this segment of their product line.

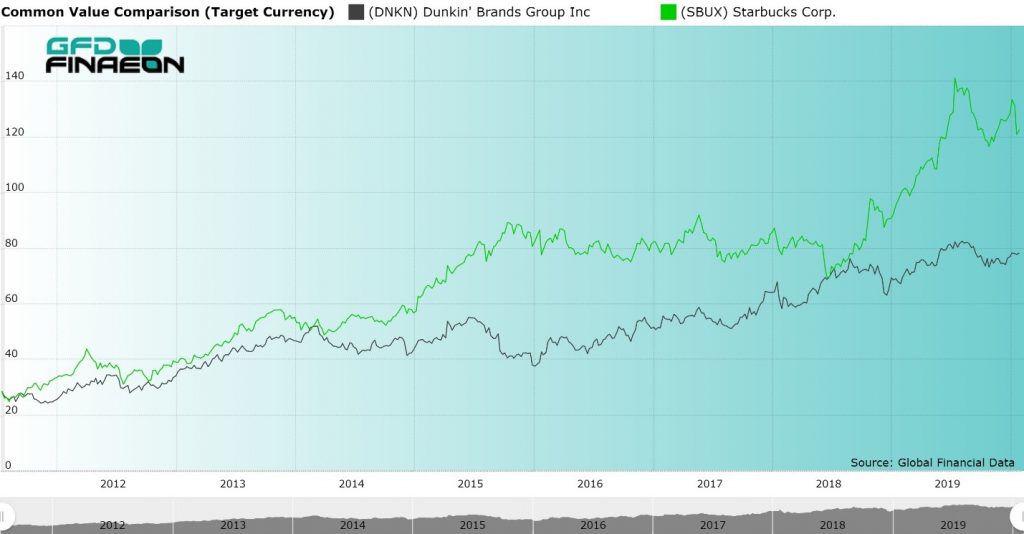

In December 2005, Pernod Ricard SA, sold Dunkin’ Brands, to three private equity groups: Thomas H. Lee Partners, the Carlyle Group and Bain Capital for $2.43 billion. Thomas H. Lee, Carlyle Group and Bain all had vast fast food experience. Each had an equal share in Dunkin’, each desired to be partners, and each wanted to work with the existing Dunkin’ management team and CEO Ron Luther. Their combined goal was to take the chain to the next level. Their plans were aggressive seeking expansion to the west, to offer additional franchises, branch into more coffee beverages, offer higher-end, glamorous coffee drinks that would compete with Starbucks. The results are can be seen in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Dunkin’ Brands Inc. (Black) vs. Starbucks Inc. (Green), 2011 to 2020

Five years later with a thriving business, T.H Lee, Carlyle Group, and Bain Capital applied for an I.P.O. and the company went public in 2011. The company had 97 million shares outstanding making the company worth $2.7 billion when it IPO’d on July 27, 2011, providing the three private equity groups, each with a 10% return, over their cost of buying the company in 2005.

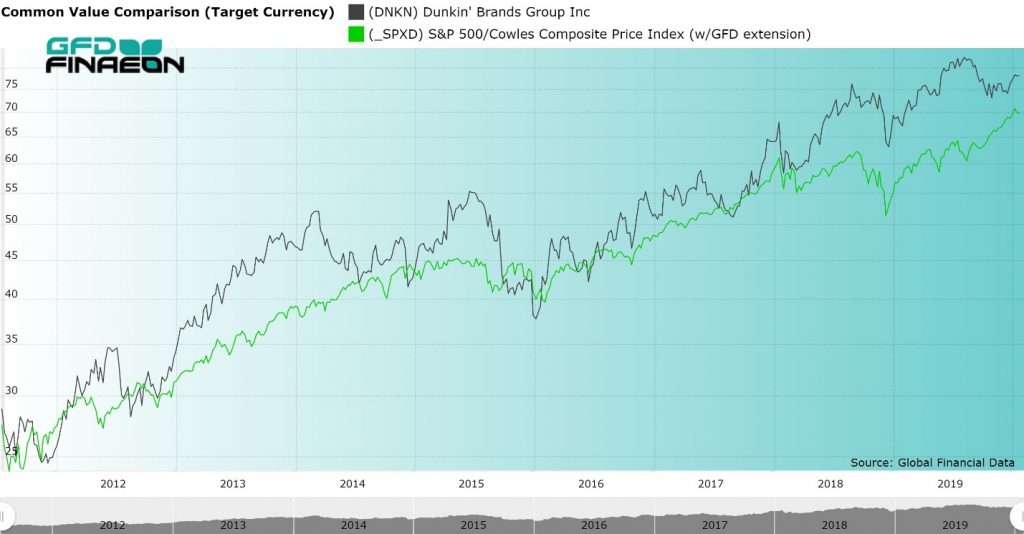

During the past eight years, as Figure 7 shows, Dunkin’ Brands has outperformed the S&P 500. The company is now worth over $6.5 billion, providing a 13% annual return to anyone who invested in the IPO in 2011. Today DNKN trades on the Nasdaq and consistently shows rising sales, profits and the number of its locations. Due to Rosenberg’s brilliant observations and his ability to respond to consumer needs, he was able to build his business.

Figure 7. Dunkin’ Brands Group (Black) vs. S&P 500 (Green), 2011 to 2020

Dunkin’ Brands currently includes the Dunkin’ Donuts chain, Baskin-Robbins ice cream parlors and Togo’s sandwich stores. In the United States and the rest of the world, the growth of Dunkin’ Donuts has been strong. Today, Dunkin’ Donuts offers a mind-boggling mix of over 15,000 varieties of coffee. This includes Turbo Shots, Espresso, Iced Coffee, sugar free, with or without cream, low-calorie options, and dozens of other variations of the world’s favorite beverage, coffee! Some of the flavors you can get include Butter Pecan Swirl, Caramel, Cookie Dough, White Chocolate Raspberry and Rocky Road swirl.

I hadn’t even heard of all these flavors of coffee before. Had you? I think that I’m going to check out Dunkin’ Donuts later this week.

On December 9, Paul Volcker, who served as Chairman of the Federal Reserve Bank from 1979 to 1987, died at the age of 92. Paul Volcker changed the shape of the economy and of financial markets.

The Rise and Fall of Interest Rates

Paul Volcker is known for two things. He instituted the Volcker Rule as part of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. This prohibited banks from conducting some investment activities with their own accounts and limited their dealings with hedge funds and private equity funds.

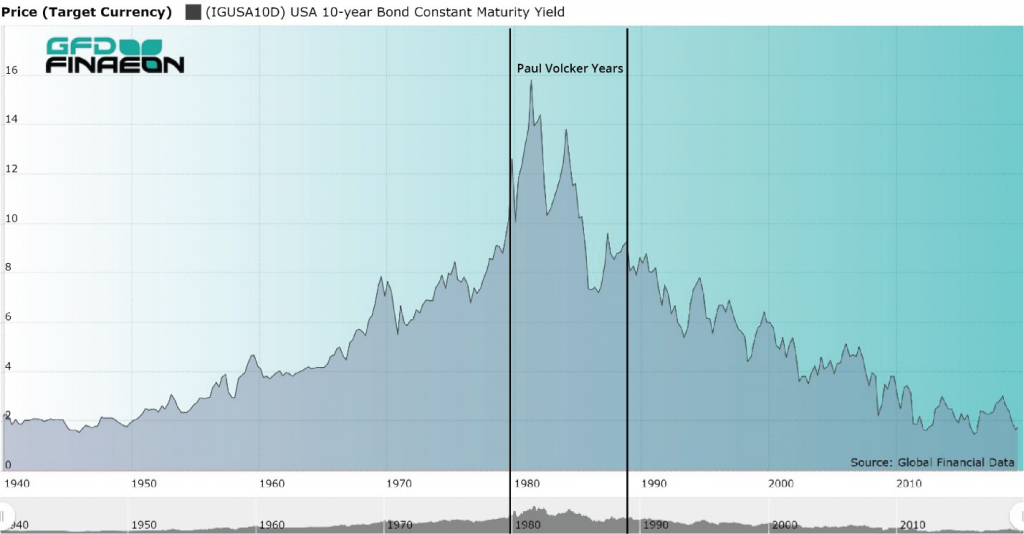

Figure 1. USA 10-year Government Bond Yield, 1940 to 2019

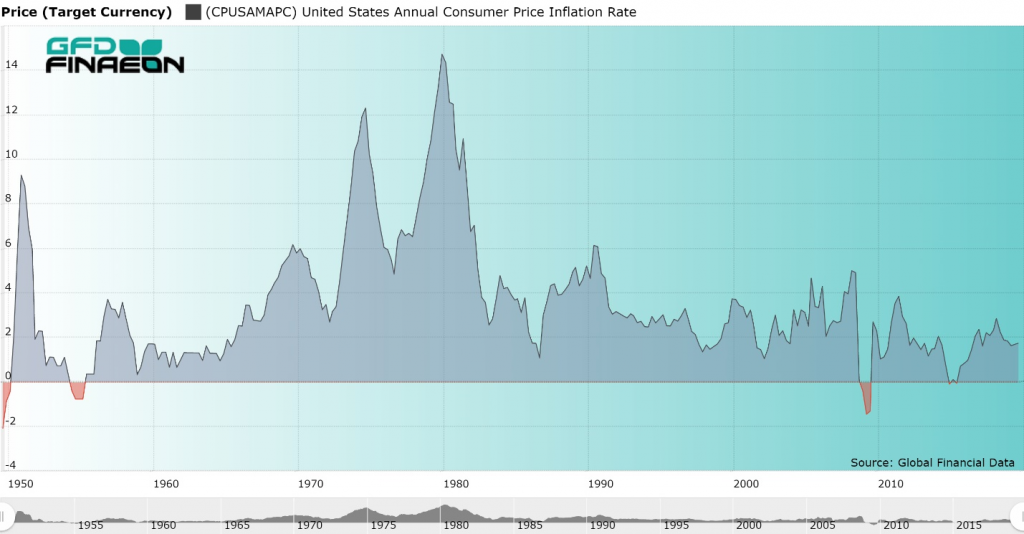

Figure 2. United States Inflation Rate, 1950 to 2019

Second, Paul Volcker defeated the rising inflation and interest rates of the 1970s. In 1981, the yield on the 10-year bond peaked at 15.84% as can be seen in Figure 1. Today, the bond yield and inflation are both below 2% as depicted in Figures 1 and 2. Government bond yields in most of the Euro zone are negative in nominal terms and are negative in real terms in the United States. There is no sign that bond yields, interest rates or inflation will reverse and begin rising in the near future. If anything, bond yields are likely to continue to decline in the United States.

Paul Volcker Reverses 40 Years of Rising Rates

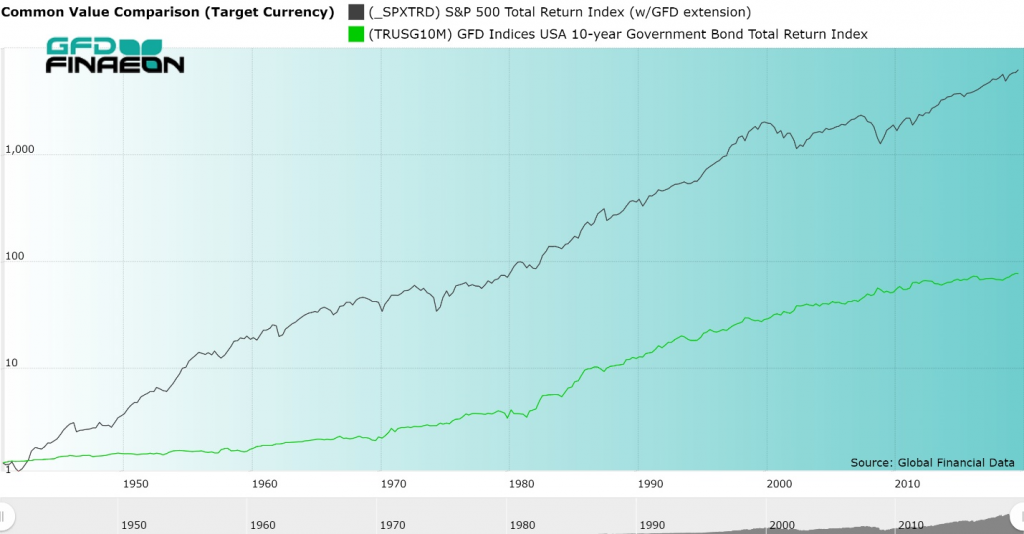

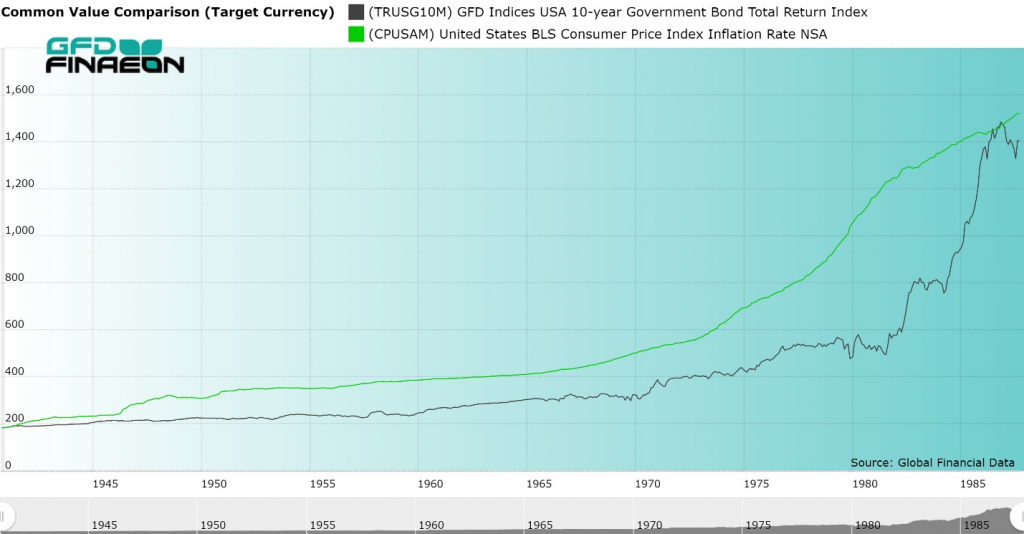

Paul Volcker instituted major changes that impacted investors. Between 1792 and 1941, stocks provided a 6.80% return while bonds provided a 4.99% return. Then the great Keynesian inflation began. Between 1941 and 1981, US equities returned 11.38% while the 10-year bond returned only 2.75% as can be seen in Figure 3. Inflation averaged 4.60% during those 40 years meaning that after inflation bond investors actually lost money as is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 3. S&P 500 Composite Total Return and Government Bond Total Returns, 1940 to 2019

However, between 1981 and 2018, stocks returned 11.13% and bonds returned 8.04%. This is illustrated in Figure 4. Bonds made no progress from 1940 to 1981, then provided dramatic returns from 1981 to 2019. The cause of this change was Paul Volcker. Although there was little difference in the annual return to equities, the return to bonds rose significantly as the decline in bond yields produced capital gains rewarding bond investors.

Figure 4. United States Government Bond Return Index and Consumer Prices, 1941 to 1987

The years between 1941 and 1981 were atypical of American financial history. The equity risk premium rose from 1.72% between 1792 to 1941 to 8.40% between 1941 and 1981. As equity markets recovered after World War II, bond investors were punished with rising bond yields, and many investors falsely interpreted the high returns as the standard for the equity risk premium.

Figure 5. U.S. Government Bond Returns Adjusted for Inflation, 1940 to 2019

The Death of the Equity Risk Premium

Investors began to expect high returns on stocks; however, between 1981 and 2018, the equity risk premium fell back to 2.75%. This is illustrated in Figure 6. In some countries, such as Canada, government bonds have beaten the stock market since 1981. Most people believe that the equity risk premium is around 6% or even more when historically, except for the period between 1941 and 1981, the equity risk premium has been around 3%. Although bond yields may still decline in the next few years, the room for decline is minimal.

The 2020s have begun. During the 2010s, the fixed-income market has done things no one would have predicted when the 2010s began ten years ago. The most important feature of the past decade has been the steady decline in government bond yields, falling to negative nominal yields in most of Europe and negative real yields in the United States and Canada.

Government bond yields have been declining since 1981 throughout the world. In the United States, the 10-year bond yield was 3.85% at the end of 2009, but has declined to under 1.90% today. The yield on 10-year government bonds in Japan has declined from 1.30% in 2009 to -0.06% in 2019 while German bond yields have declined from 3.37% to -0.30%. Across the world, interest rates are negative in real terms. In Switzerland, even the 50-year bond has a negative return.

I believe that interest rates cannot continue to decline. Why accept a negative return when you can always hold cash with a zero return? There are transaction costs of buying and selling bonds. Although these costs can be easily factored into a long-term bond, this is more difficult with a short-term bond. Will the 38-year bull market in bonds driven by declining yields come to an end? Is a new multi-decade pattern of rising bond yields replacing the declining yields of the past few decades? There are over $10 trillion in outstanding government bonds with negative yields in the world. Many of these bonds are owned by governments so the yield is almost irrelevant. Will bond yields still be negative ten years from now? Will interest rates decline or rise during the decade to come?

The Interest Rate Pyramid

We are currently in a 75-year cycle of rising and falling interest rates. The government controlled interest rates during World War II to limit the government’s cost of funding the debt it issued to pay for the war. When the war was over, the government allowed the market to once again determine bond yields, and the government’s policies fed inflation driving prices and bond yields up between 1945 and 1981. Paul Volker decided to fight inflation at any cost and reversed the pattern of rising inflation and interest rates. Inflation and bond yields have declined since 1981 falling from 15.81% in 1981 to under 2% today.

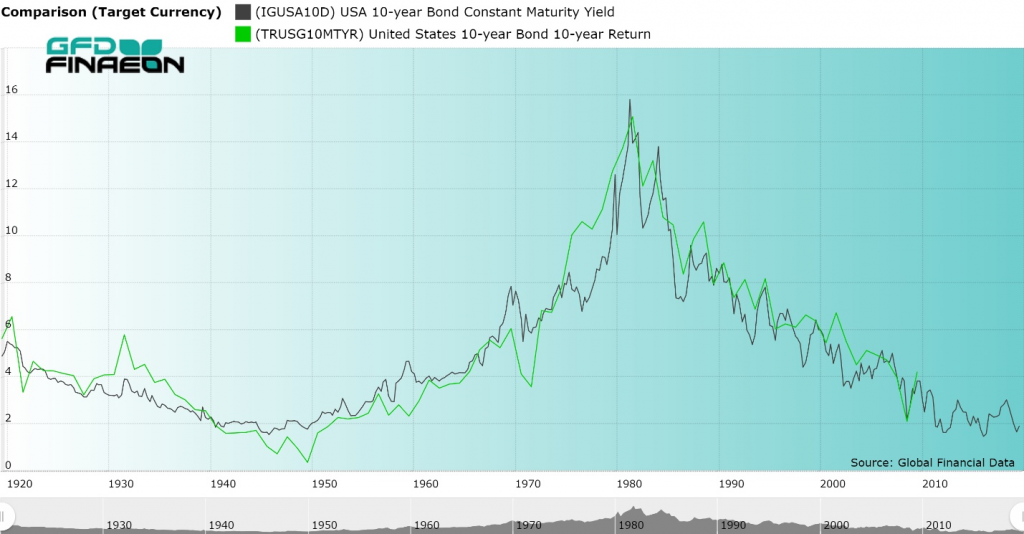

Figure 1. United States 10-year Government Bond Yield and Return, 1919 to 2019

Fixed-income investors are concerned about two factors, the capital gain or loss they receive when there is a change in the bond yield and the interest payments they receive each six months from the government. GFD’s 10-year Total Return Government Bond index takes both of these factors into consideration in calculating the total return to holders of government bonds. During the period of rising interest rates between 1945 and 1981, bondholders received higher interest payments over time, but lost money as higher interest rates drove the price of bonds down. The opposite effect has occurred since 1981.

What is interesting is that the capital gain/loss that occurs because of rising or falling bond yields offsets the interest bondholders receive to even out the return to investors. The assumption is that as the bondholder receives interest payments over time, this money is reinvested in government bonds at the current yield in the market. In theory, the bondholder could completely reinvest his principal and interest in a new bond each year. Bondholders can also invest in mutual funds that effectively do this for them. The interesting thing is that over the past 75 years, the capital gain/loss that has been generated by the rising and falling bond yields has offset the rising and falling coupons that have occurred over time.

Figure 1 compares the yield on the US 10-year bond in black with the total return to an index of bonds invested in 10-year government bonds in green. The return index compares the return to government bond holders between 2008 and 2018 with the yield to government bonds in 2008. Of course, you would have needed to wait until 2018 to find out what the return was to investors in government bonds in 2008, but as Figure 1 shows, the correlation between the yield on government bonds at any point in time and the actual return investors receive over the next ten years is uncanny. The fact that this pattern has persisted for the past 100 years is amazing.

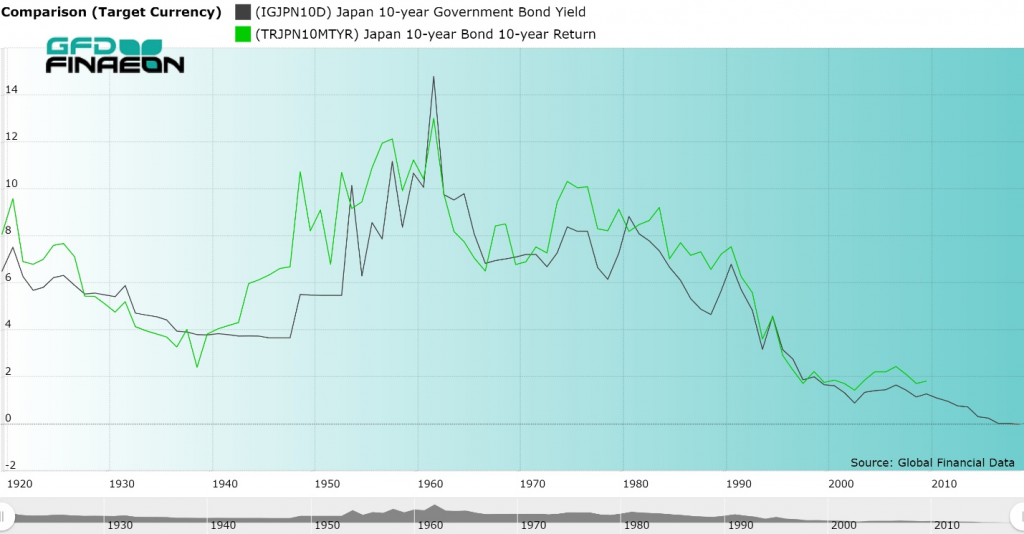

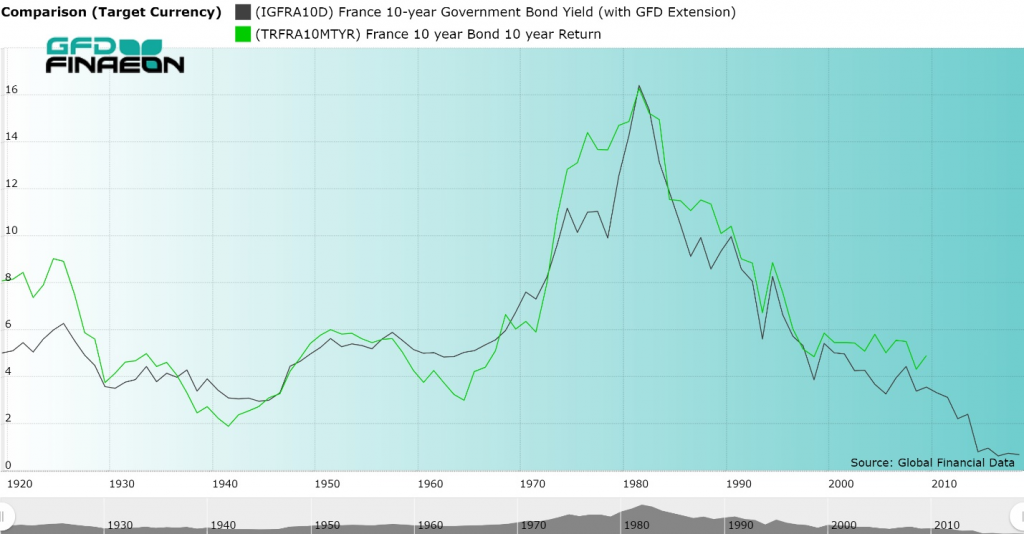

Examining other countries, you get similar results. Figure 2 shows the relationship between bond yields and returns for Japan and Figure 3 shows the relationship for France. The relationship between bond yields and returns is not always as strong as it is in the United States, but the general relationship still exists.

Figure 2. Japan 10-year Government Bond Yield and Return, 1919 to 2019

Figure 3. France 10-year Government Bond Yield and Return, 1919 to 2019

The Decade to Come

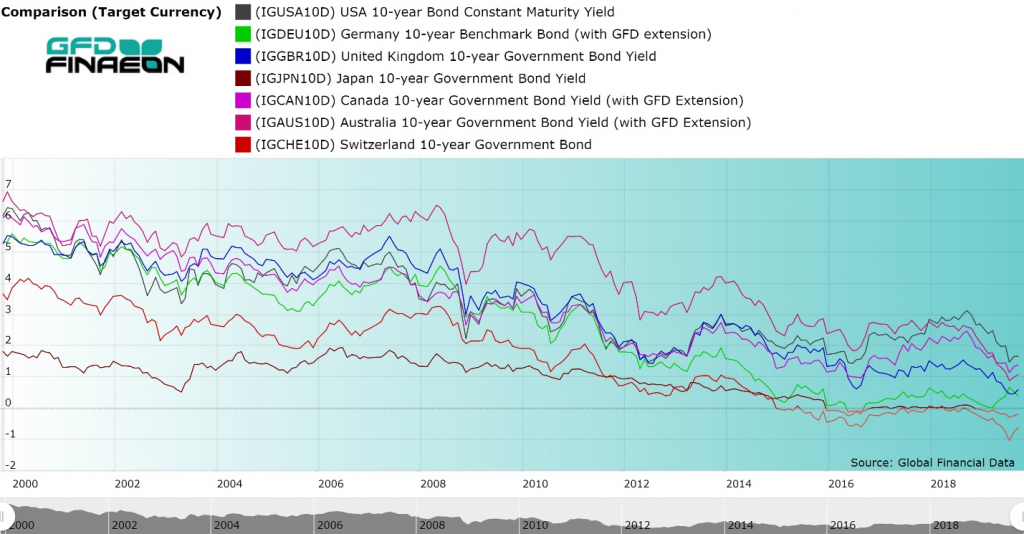

Examination of global bond yields in Figure 4 compares bond yields over the past 20 years in the United States, Germany, the United Kingdom, Japan, Canada, Australia and Switzerland. Interest rates in Germany, Japan and Switzerland have turned negative, and after adjusting for inflation, you would find that real yields in the remaining countries are negative.

If you look at the yield and return graphs for the United States, Japan and France in Figures 1, 2 and 3, you will see that the returns are not provided after 2009 because we don’t know what the behavior of bonds in the 2020s will be and thus cannot calculate the total return to bondholders between 2012 and 2022, for example, because this number will not be known until 2022.

Figure 4. 10-Year Government Bond Yields for Seven Countries, 2000 to 2019

The inevitable logic that would come from this analysis so far is that if the yield on government bonds declined in the 2010s as they did in the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s, then a continued decline in government bond yields during the next decade is the most logical outcome. If bond yields were to rise, this would impose capital losses on bondholders, driving the total return to negative levels even below the yields that persisted in the 2010s.

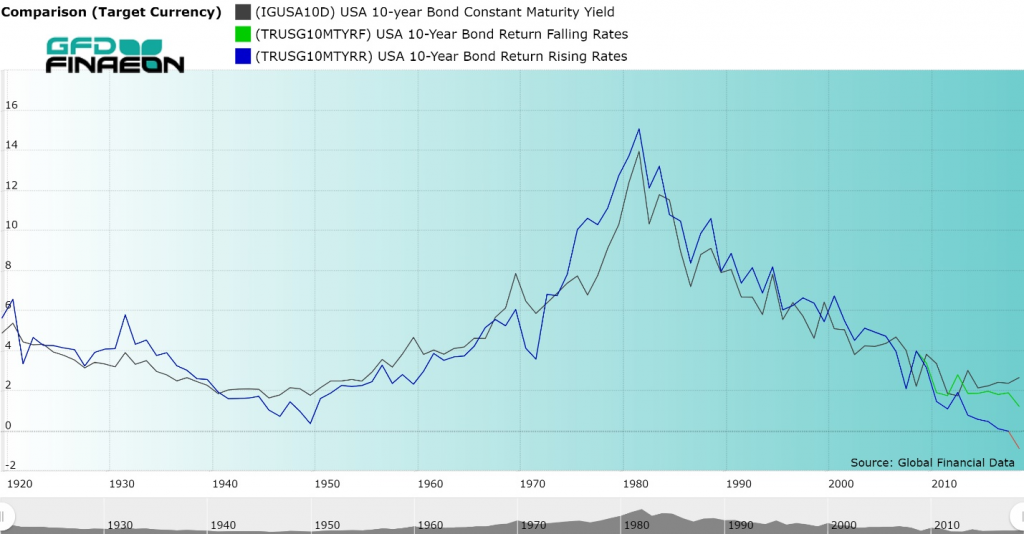

To illustrate this fact, I have calculated what the total return to US government bondholders would be if bond yields rose by 0.125% in each of the next ten years and if they fell by 0.125% annually starting at a yield of 2% at the end of 2019. With these assumptions, I can calculate both the return from interest payments and the impact on the price of government bonds as the money was reinvested. I provide the results in Figure 5. In reality, bond yields will not rise or fall each year at a constant rate, but will fluctuate. The overall results will be the same regardless.

Figure 5. United States 10-year Government Bond Rising and Falling Yields and Returns

The black line in Figure 5 shows the path of government bond yields through 2019. The green line shows the returns that would occur if interest rates fell by 0.125% each year for the next 10 years, and the blue line shows what would happen if interest rates rose by 0.125% each year for the next 10 years. The cumulative effect of rising interest rates would be to generate negative returns to bondholders from 2019 by 2029. On the other hand, if government bond yields continue to fall, the decline in the total return is reduced by the capital gain shareholders would receive allowing returns to follow more closely to the bond yields that existed in the 2010s. Since the green line of falling interest rates adheres more closely to the actual behavior of interest rates between 2009 and 2019, it would seem more logical to predict falling interest rates over the course of the 2020s than rising interest rates.

Trouble in Bond Paradise

Whether you expect bond yields to rise or fall over the next 10 years, the conclusions reached in this paper should raise concerns for any fixed-income investor. If government bond yields rise over the next 10 years, by the end of the decade, if not earlier, fixed-income investors will receive a negative return on their investment. On the other hand, the only way for fixed-income investors to avoid negative returns is to hope for falling bond yields. Rising bond prices will offset the decline in yields, but at the same time may only delay the inevitable losses that fixed-income investors will eventually have to incur when interest rates rise at some point in the future.

What is true of the United States is true of the rest of the world. As Figure 4 indicates, 10-year government bond yields are lower than they are in the United States in virtually every developed country in the world. There is currently over $10 trillion in notes and bonds with a negative yield. If bond yields don’t rise, investors will receive a negative return because of rising bond prices. If bond yields do rise, investors will receive a negative return because of rising bond prices.

Some would say that a return to rising bond yields is inevitable, but this isn’t necessarily true. Bond yields fell throughout the 1800s. Yields fell from 5.345% in 1803 to 2.43% in 1897. There is no reason why bond yields might not fall for decades if the Federal Reserve can keep inflation under control. Population growth and economic growth may remain stagnant and constrain any increase in inflation or interest rates in the future. Data on these indicators are available through the GFDatabase and GFD Indices. All of the 10-year bond yields extend further back than is displayed in Figure 4. Fixed-income investors may be condemned to lose money during the next decade. The only question is how much?