Global Financial Data has produced indices that cover global markets from 1601 until 1815 as a first step toward creating a World Index that provides data on equities from 1601 until 2018. As we have discussed in another blog, “The Fifth Financial Era: Singularity,” you can divide financial market history over the past 400 years into four eras of Monopolies and Funds (1600-1815), Globalization (1815-1914), Regulation and Nationalization (1914-1981) and the Return to Globalization (1981-). At some point in the near future, global markets should move toward singularity in which a single market for stocks and bonds operates over the entire planet.

It cannot be understated how much equity markets were transformed between the 1700s and the 1800s. Before 1815, financial markets were primarily geared toward issuing government equities and bonds to investors who wanted consistent, reliable dividend and interest income from their investments. During the 1700s, few investors saw equity markets as a way of generating capital gains by allocating money to new industries. In fact, what differentiates equities in the 1600s and 1700s from the two centuries that followed is the lack of capital gains and investors’ almost total dependence on dividends as a source of return.

Global Financial Data has produced indices that cover global markets from 1601 until 1815 as a first step toward creating a World Index that provides data on equities from 1601 until 2018. As we have discussed in another blog, “The Fifth Financial Era: Singularity,” you can divide financial market history over the past 400 years into four eras of Monopolies and Funds (1600-1815), Globalization (1815-1914), Regulation and Nationalization (1914-1981) and the Return to Globalization (1981-). At some point in the near future, global markets should move toward singularity in which a single market for stocks and bonds operates over the entire planet.

It cannot be understated how much equity markets were transformed between the 1700s and the 1800s. Before 1815, financial markets were primarily geared toward issuing government equities and bonds to investors who wanted consistent, reliable dividend and interest income from their investments. During the 1700s, few investors saw equity markets as a way of generating capital gains by allocating money to new industries. In fact, what differentiates equities in the 1600s and 1700s from the two centuries that followed is the lack of capital gains and investors’ almost total dependence on dividends as a source of return.

The First Financial Revolution

The First Financial Revolution occurred in the early 1600s when the Dutch West India Company, the Dutch East India Company and the English East India Companies were established. The Dutch East India Company was founded in 1601 and continued until it ceased operations in 1799. The Dutch West India Company was established in 1621, went bankrupt in 1674 after losses during the Anglo-Dutch War, and reorganized as a new Dutch West India Company in 1674. The English East India Company was established in 1600 and continued in existence until 1874. Before 1600, merchants had formed “shares” in voyages that ships made to the far east, but the innovation that occurred in 1600 was to vest ownership in a single company, and not in individual voyages. This provided economies of scale and allowed capital from one voyage to be reinvested in other voyages. Shares in these companies were traded at London coffee houses and on the exchanges in Amsterdam and Paris. Of course, many international corporations existed in the 1600s, but few were of sufficient size to enable shares to be traded on a regular basis. In the 1500s, English companies were established enabling the British to trade with Guinea, Senegal, Russia and the Levant, but most of these companies were too small to create a financial market for their shares. What is important about the First Financial Revolution was that it established the principal of founding corporations that could issue shares which did not expire. Shareholders could buy and sell their shares to others, and receive dividends if the company were profitable. A second wave of incorporations occurred in the 1690s. In the Glorious Revolution of 1688 English parliamentarians overthrew King James II and established a constitutional monarchy in England. This not only brought a Dutch ruler to London, but also brought Dutch capital and Dutch financial knowledge. The Phipps treasure-seeking expedition of 1687-1688 paid a 10,000% dividend to shareholders encouraging other corporations to be established. In 1694, the activity in stocks in London was sufficiently large that John Houghton wrote articles on share trading and published a list of the prices of shares traded in London. In January 1698, the Course of the Exchange began its regular bi-weekly publication which lasted into the 1900s. The Amsterdamsche Courant published Dutch share prices fortnightly beginning in 1723, and Les Affiches de Paris began publishing the price of shares traded in Paris in 1745. Between these three publications, we have been able to put together data on share prices from 1601 until 1815. The 1600s and 1700s were a period of almost continual war in Europe and the debt of the English, Dutch and French rose as a result. Governments in the Netherlands and Great Britain began issuing debt that had longer maturities, in some cases creating annuities that provided annual payments as long as the bondholder was alive. These debt instruments eventually were converted into perpetuities which never matured just as shares in the East India Company and the Bank of England never matured. Given the choice of obtaining a perpetuity that paid a fixed yield from a government or variable dividends from a corporation, most investors chose to invest in the government security. Because of its consistency in payment, Britain was able to increase its debt to twice its GDP by 1815 while the yield on government debt fell from 8% in 1701 to 3% in 1729 when the annuities were introduced. Between 1688 and 1789, British government debt grew from £1 million in 1688 to £244 million in 1789 and £745 million in 1815. During that same period of time the market cap of British shares grew from £1 million in 1688 to £30 million in 1789 and £60 million by 1815. The market cap of shares, which was equal to outstanding government debt in 1688 shrank to less than 10% of government debt by 1815. Although the number of available bonds and shares was limited, the market was global. In the 1780s, government debt from Spain, Austria, Russia, Sweden, France and Great Britain all traded in Amsterdam. But the Napoleonic wars led to default by all of these countries except Great Britain. By 1800, the Dutch West India Company and Dutch East India Company as well as the French East India Company were all driven into bankruptcy.Equity markets in the 1600s and 1700s

Data on companies from the 1600s is extremely limited. Data are available for only two companies from the Netherlands, the Dutch East India Company (1601-1698) and the Dutch West India Company (1628-1650). The data before 1690 depends almost exclusively on the Dutch East India Company which was the largest corporation in the world in the 1600s and one of the largest corporations in financial history. For more information on the Dutch East India Company, see the blog, “The First and the Greatest: The Rise and Fall of the United East India Company.” Nevertheless, we have price data, shares outstanding and dividend information, the three primary components that are needed to put together a stock market index. Unlike corporations in England, shares in the Dutch East India Company were allocated by municipality, many dividends were paid in kind, shares could not be traded and cleared as easily as they were in London, and the company never issued new shares, but instead issued so much debt that the company eventually went bankrupt. The key event for financial markets between 1600 and 1815 was the Bubble of 1719-1720. The Dutch, French and British governments all issued large amounts of debt to fight the War of the Spanish Succession between 1701 and 1713. John Law offered the French a way of converting their government debt into equity in the French East India Company. In Britain, investors were allowed to convert their debt into shares in the South Sea Company. Enthusiasm for the shares and government manipulation drove prices of the stocks up to unsustainable levels. Governments in both Paris and London passed laws that directed all capital into the French East India Company and the South Sea Company, but after the crash, companies were restricted from raising additional capital and few companies issued new shares for the rest of the 1700s. Almost all of the activity in the Netherlands came from the Dutch West India Company and the Dutch East India Company. The only other company of any prominence was the Societeit von Berbice which settled Dutch Guyana. The French East India Co. was the primary corporation that traded in Paris until the Caisse d’Escompte and Compagnie des Eaux de Paris began trading in 1787. These corporations ran into problems during the French Revolution. On August 24, 1793, the Committee of Public Safety banned all joint-stock companies and seized the assets and papers of the French East India Company. Directors of the company bribed French officials so the company could oversee its liquidation rather than the government. When this was discovered, key Montagnard deputies were executed, leading to the downfall of Georges Danton. We have to rely on the London Stock Market for most of the companies that make up the world index between 1692 and 1815. Among the more important companies for which we were able to collect data on prices, dividends and shares outstanding were the Royal African Company (1692-1742), the East India Company (1692-1815), the Bank of England (1694-1815), the New East India Company (1698-1708), the Million Bank (1700-1749), the South Sea Co. (1711-1815), the London Assurance Co. (1720-1750) and the Royal Exchange Insurance Co. (1735-1753). The Bank of Scotland was founded in 1695, the Royal Bank of Scotland in 1727 and the British Linen Co., which acted as a bank, in 1745, but unfortunately, data on these and other companies was unavailable for inclusion in the index. Although London lacked a formal exchange until 1801, trading occurred at coffee shops around Exchange Alley and the prices of shares were recorded in The Course of the Exchange. In addition to shares, the 3% Annuities began trading in 1729 and the 3% Consolidated Bonds in 1757. Other government debt was issued and traded, but most of the activity in London, Paris and Amsterdam was in English bonds. Only companies for which we were able to obtain share price data, share outstanding data and dividends are included in the index. Any company that lacked all of these three variables was excluded.Returns to Stocks and Bonds

Table 1 shows the returns to stocks and bonds in France, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, the United States and the world from 1602 until 1815. Unfortunately, the years covered by each country differs so direct comparisons between the returns to stocks and bonds in different countries is difficult. What is obvious is the overall lack of capital gains. Almost all of the return came from dividends for stocks and interest for bonds.| Table 1. Annual Returns to Stocks and Bonds, 1602 to 1815 | |||||

| Country | Securities | Years | Price | Dividends | Return |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| France | Bonds | 1746-1815 | -0.23 | 3.17 | 2.93 |

| France | Stocks | 1718-1793 | -1.78 | 6.95 | 5.05 |

| France | Stocks | 1801-1815 | -1 | 5.31 | 4.26 |

| Netherlands | Bonds | 1788-1815 | -6.27 | 2.85 | -3.6 |

| Netherlands | Stocks | 1602-1794 | -0.24 | 4.76 | 4.51 |

| United Kingdom | Bonds | 1700-1815 | -0.23 | 4.46 | 4.22 |

| United Kingdom | Stocks | 1692-1815 | 0.08 | 4.57 | 4.65 |

| United States | Bonds | 1786-1815 | 3.54 | 4.86 | 8.57 |

| United States | Stocks | 1791-1815 | -0.76 | 6.5 | 5.69 |

| World | Bonds | 1700-1815 | 0.2 | 5.52 | 5.73 |

| World | Stocks | 1602-1815 | 0.95 | 5.7 | 6.7 |

The Period of Monopolies and “the Funds”

The bonds that were issued by the British government was known as “the Funds”, and the period from 1600 to 1815 differed from the period after 1815 in several important ways. 1. There were only a handful of companies available to investors before 1815; after that, there were hundreds. 2. Most of the companies that existed before 1815 were tied to the government, not private corporations that developed new industries. 3. Before 1815, almost all of the return came through dividends, but after 1815, capital gains became increasingly important to investors. 4. During the Napoleonic Wars, outside of England, national government bonds almost all defaulted on their debt and corporations went bankrupt. 5. Before 1815, government debt grew dramatically while the market cap of equities changed little. After 1815, these trends reversed and government debt declined relative to GDP while the market cap of shares increased dramatically. The lack of any major wars between 1815 and 1914 freed up capital that was used to build the infrastructure of the world. Although the first stock markets were established in 1600, stock markets as we know them today weren’t really established until the 1800s when shares in hundreds of corporations became available to investors. The performance of shares after 1815 will be covered in a future blog.Global Financial Data has produced indices that cover global markets from 1601 until 2018. In organizing this data, we have discovered that the history of the stock market over the past 400 years can be broken up into four distinct eras when economic and political factors affected the size and organization of the stock market in different ways. Politics and economics define the limits of financial markets by determining whether companies can exist in the private or the public sector, by controlling the flow of capital in financial markets, and by determining the level of regulation that companies face in maximizing their profits. The first era covers the period from 1600 until 1815 when financial markets funded government bonds and a handful of government monopolies. The British East India Company was established in 1600. For the next 200 years, financial markets traded a very limited number of securities. After the bubbles of 1719-1720, shares traded more like bonds than equities. Investors were more interested in getting a secure return on their money than investing for capital gains. The second period from 1815 until 1914 was one of expanding equity markets, globalization of financial markets, and a reduction in the importance of government bonds relative to equities. This changed in the 1790s when first canals, and later railroads changed the nature of financial markets forever. Investors discovered that transportation stocks could provide reliable dividends as well as capital gains. For the next hundred years, investors had the opportunity to invest in thousands of companies that could generate capital gains as well as dividends. Financial markets became globalized and the transportation revolution enabled the global economy to grow. By 1914, capital flowed freely throughout Europe and the rest of the world, enabling investors to optimize returns globally. The era of globalized financial markets came to an end on July 31, 1914 when the world’s stock markets closed down when World War I began. During the war, capital was directed toward paying for the war. Attempts to restore globalized financial markets after the war failed. Financial markets operated on a national level, not on an international level. Before World War I, markets provided similar returns because they were integrated. After the war, national equity market returns diverged because capital was unable to flow to the countries with the highest rates of return. After World War II, Europe nationalized many of its main industries and the United States regulated industries. It wasn’t until the 1980s that equity markets became globalized once again when deregulation and privatization swept over the world’s stock markets. The poor performance of markets and the economy in response to the OPEC Oil Crisis of the 1970s brought the role of government in regulating the economy into question. Privatization swept over the capitalist economies, and the former Communist countries opened stock markets and began to integrate with the world’s financial markets. The global market capitalization/GDP ratio increased dramatically. There is no definitive date when this transition occurred, so the bottom of the bear market in bond and equities in 1981 is used as the starting point of this new era. How long the fourth era will last before we move into a fifth era will depend upon technology. The fifth financial era will begin when financial markets reach singularity, where the national markets in financial assets merge into one market and financial markets are not just global, but singular. All financial assets will trade 24 hours a day over computer networks that are connected to every corner of the globe. Markets have almost reached that point in the foreign exchange market, and it is only a matter of time before the market for financial assets reaches that point as well.

The First Era: Monopolies and Funds

A Financial Revolution occurred in 1600 when the Dutch East India Company and the English East India Companies were established. The Dutch East India Company was founded in 1601 and continued to operate until 1799. The English East India Company was established in 1600 and reorganized three times before the fourth East India Company was established in 1657. That company lasted until 1874. Before 1600, merchants had created “shares” in voyages that ships made to the far east. By investing in several ships, merchants could reduce their risk. The innovation of the Dutch East India Company was to vest ownership in the company, and not in individual voyages. This provided economies of scale and by creating perpetual life for the corporation, allowed capital from one voyage to be reinvested in other voyages. What is important about the Financial Revolution of 1600 was that it established the principal of founding corporations that could issue shares which did not expire. Shareholders could buy and sell their shares to others, and receive dividends if the company was profitable. Nevertheless, the Dutch East India Company made several mistakes which future companies learned from. The Dutch East India company allocated its shares by municipality, which limited trading in its shares. The company did not raise additional equity capital by issuing new shares, but borrowed money which increased its debt-to-equity ratio and eventually ended up bankrupting the Dutch East India Company. Moreover, dividends were often paid in kind. Instead of receiving cash dividends, shareholders would receive cloves brought back from the West Indies. Merchants were happy to receive payment in kind and sell the cloves, but investors preferred cash payments. A second wave of incorporations occurred in the 1690s following the Glorious Revolution of 1688, during which English parliamentarians overthrew King James II and established a constitutional monarchy in England. This not only brought a Dutch ruler to London, but also brought Dutch capital and Dutch financial knowledge. In 1688, Amsterdam financial markets were more sophisticated than London’s. Joseph de la Vega’s Confusion de Confusiones was published in 1688 to show the Jewish community of Amsterdam the inner workings of stock markets. When the William Phipps treasure-seeking expedition of 1687-1688 paid a 10,000% dividend to shareholders, it encouraged other corporations to be established for investors to profit from. In 1694, John Houghton began writing articles on share trading and in January 1698, the Course of the Exchange began its regular bi-weekly publication, publishing trade prices collected from London coffee houses. A similar publication for Amsterdam was the Amsterdamsche Courant which published share prices fortnightly beginning in 1723. Les Affiches de Paris began publishing the price of shares traded in Paris in 1745. By the middle of the 18th century, the growth of the financial press reflected the growing interest in financial markets. Between these three publications and others, GFD has been able to put together data on share prices from 1601 until 1815. The 1600s and 1700s were a period of continual war in Europe and the debt of the English, Dutch and French rose as a result. Governments in the Netherlands and Great Britain began issuing debt that had longer maturities, in some cases creating annuities that provided annual payments as long as someone was alive. These debt instruments eventually were converted into perpetuities which never matured just as shares of stock in the East India Company or the Bank of England never matured. Given the choice of obtaining a perpetuity that paid a fixed yield from a government and variable dividends from a corporation, most investors chose to invest in the government security.

The key event for financial markets was the bubbles of 1719-1720. The market cap of British equities steadily rose from 1688 until 1720 as is illustrated above. The Dutch, French and British governments all issued large amounts of debt to fight the War of the Spanish Succession between 1701 and 1713. John Law offered the French government a way of converting their debt into equity in the French East India Company. In Britain, investors were allowed to convert their debt into shares in the South Sea Company. Enthusiasm for the shares drove prices of the stocks to unsustainable levels, but after the crash in 1720, companies were restricted from raising additional capital and few companies issued new shares for the rest of the 1700s. Investors wanted a reliable cash flow, and after the bubbles of 1719-1720, only the largest monopolies backed by the government were seen as reliable enough to warrant investment. Most financial capital went into government bonds. Even the few companies that survived the bubble behaved more like bonds than equities, changing little in price. Between 1688 and 1789, British government debt grew from £1 million in 1688 to £244 million in 1789 and to £745 million in 1815. During that same period of time the market capitalization of British shares grew from £1 million in 1688 to £30 million in 1789 and £60 million by 1815. The market cap of shares, which was equal to outstanding government debt in 1688 shrank to less than 10% of government debt by 1815. Because of its reliability in payment, Britain was able to increase its debt to levels twice GDP by 1815, while the yield on the debt declined, falling from 8% in 1701 to 3% in 1729 when the annuities were introduced.

The Second Era: Globalization

The process of globalization began in the 1780s and continued to grow until 1914. The Bank of Ireland and the Grand Canal went public in 1783-1784, and government debt from the major European powers traded on the Amsterdam stock exchange in the 1780s. However, the Napoleonic Wars bankrupted most of Europe. During the Napoleonic Wars, the Dutch West India Company and Dutch East India Company as well as the French East India Company were all driven into bankruptcy while the Netherlands, France, Austria, Russia, Spain, Sweden and the United States all defaulted on their debt. Britain was the only country that didn’t default. French and Dutch debt was reissued at a loss to bondholders, but British debt continued to pay on time attracting more investors to British government debt. It cannot be understated how much equity markets were transformed between the late 1700s and the early 1800s. Before 1815, British financial markets were primarily geared toward issuing bonds, or “the Funds” as they were called, to investors who wanted consistent, reliable dividend and interest income from their investments. In the 1790s, things started to change. The first canal bubble occurred in the 1790s as dozens of canals in the midlands of England issued shares to raise capital to build canals across Britain. In 1789, Alexander Hamilton reorganized the finances of the United States and the Bank of the United States was founded in 1791, issuing $10 million in capital to investors. The Bank of the United States was followed by the incorporation of dozens of other banks and insurance companies that raised capital in the United States. The Federal government and state governments all issued new debt. The Banque de France was established in 1800, the London Stock Exchange was founded in 1801, and The Course of the Exchange expanded to two pages, covering over 100 companies in 1811. The canal mania of the 1810s, the Latin American mania of the 1820s and the Railroad mania of the 1840s created hundreds of new companies that investors bought shares in as a way to make quick profits in financial markets. Debt from American states and the French Funds were listed in The Course of the Exchange in 1825. During the 1830s, new railroad companies were established throughout Europe and the United States and millions of dollars were poured into these companies. Europe remained at peace from 1815 until 1914 and government debt as a share of GDP declined. This is illustrated in Figure 2 below which shows the continuous rise in British government debt from almost nothing in 1688 to over 200% of GDP by 1815 and steadily declined to 1914.

The market cap of equities rose steadily as British debt declined as is illustrated in Figure 1. The market capitalization of British equities as a share of GDP rose between 1688 and 1720, then declined from 1720 until 1800. The market cap of shares began to rise in the 1840s and continued to increase until 1914 when the market cap of outstanding shares exceeded GDP. During the same time, outstanding British government debt declined from over 200% of GDP in 1815 to under 30% in 1914. The growth in investment in equities wasn’t limited to railways. British capital flowed to investments outside of Britain after 1860, going into American railways, Indian railways, Argentine and Brazilian shares and other equities. Britain helped build the railways of the world. Capital also went into government bonds. Japan issued its first bonds in London in 1870, and dozens of other countries followed in their footsteps. A similar pattern occurred in the United States where the ratio of market capitalization to GDP rose dramatically between the beginning of the Civil War and the beginning of World War I. The market capitalization of US equities was only about 10% of GDP in 1860, but rose to 70% by the beginning of World War I. Most of this money went into railroads, but it also flowed into Standard Oil, U.S. Steel, General Motors and dozens of other industrial companies. There were direct links between London and New York that enabled British investors to buy shares directly in New York and in other financial capitals.

Although these financial trends were most apparent in Britain and the United States, the globalization of financial markets occurred in every market in the world. By the beginning of World War I, there were hundreds of companies trading simultaneously in New York, Paris and Berlin. London became the financial center of the world. Not only was London able to fund railroads that in Britain, but London also funded railroads, banks and utilities in almost every country in the world. London funded companies not only in all of its colonies, including Canada, India, South Africa and Australia, but also in Latin America, Mexico and the United States. Although the United States funded the majority of the railroads that stretched from the Atlantic to the Pacific, British and Dutch investors pour hundreds of millions of dollars into American equities and bonds. South African mining companies excited investors in London, Paris and Berlin during the late 1800s and early 1900s. Equity and bond markets were truly global and billions of pounds were invested in new stocks and bonds every year. We can divide the process of globalization into two periods. During the first period from the 1830s until the 1860s, corporations were able to raise money in London, Paris and Berlin to build railroads that covered the European continent. By the 1870s, Germany and Italy were unified and the gold standard fixed exchange rates between all the world’s major economies. From the 1860s until 1914, capital flowed from London to the rest of the world to build the global infrastructure in railroads, telegraphs, finance and utilities. The transcontinental railroad was built across the United States and railroads were built in India, China and other countries. The Suez Canal listed jointly in Paris and in London. Eastern European countries listed in Berlin. Russian companies listed in St. Petersburg while Chinese companies listed in Shanghai and Hong Kong. The Gold Standard provided fixed exchange rates between all the world’s global economies, making it easy to transfer money from one country to another. By 1900, it was no longer necessary to ship gold from one country to another to take advantage of exchange-rate differentials. Instead, Russian government debt or American railroads could be bought and sold to move capital from one country to another. By the beginning of the 1900s, money began flowing into industrial stocks, banks and insurance companies, mining stocks, especially in South Africa, and other new industries. Energy stocks such as Standard Oil, tobacco stocks such as British Tobacco, electricity stocks such as General Electric, automobile companies such as General Motors and hundreds of others all drew in capital when there was no place left to build railroads. The financial world in 1790 and in 1914 were completely different. In 1790 there was only a handful of companies that investors could put their money in and government debt represented 90% of outstanding financial instruments. By 1914, government debt had shrunk in size relative to GDP and through capital markets, money flowed into every country in the world to build the global economy. Virtually no one in 1913 could have guessed that this would all soon come to an end.

The Third Era: The Great Reversal

World War I destroyed the globalized financial markets which existed before 1914. By July 31, 1914, virtually every stock market in the world had closed to prevent shareholders from selling their stocks and bonds and repatriate their money. Capital was no longer free to cross borders. Financial markets faced restrictions they had never faced before. During World War I, capital flowed into government bonds, not corporate coffers. Even when stock exchanges reopened, price restrictions limited the amount of trading that could occur. The Berlin and St. Petersburg stock exchanges didn’t reopen until 1917, and the St. Petersburg stock exchange closed soon after when the October Revolution struck Russia. The period from 1914 until 1981 was one of government control over financial markets through regulation after World War I, and nationalization of the largest companies in Europe after World War II. Capital controls limited the ability of money to flow from one country to another. Stock markets’ access to foreign funds became severely limited. Before 1914, global financial markets were integrated and bond interest rates converged to the international average. After 1914, national stock and bond markets moved independently of one another and different domestic inflation rates and risk of default produced different interest rates in each country. Wars are run by governments, not by free markets. World War I and II were total wars and heavy industry, infrastructure, utilities, transports, finance were all put under the control of government in order to win the war. Once government began controlling different sectors of the economy during the war, governments wanted to maintain control through regulation or nationalization after the war. Many consumer markets evaded the purview of government control, but the government wanted to exercise control over any large corporation. Between 1914 and 1981, there was an ebb and flow between greater market freedom and greater regulation, but there was no real push for the privatization of the sectors that had been nationalized or regulated until the 1980s. There were periods when equity markets appeared to succeed in the 1920s and in the 1950s and 1960s, but during the other decades, equity markets were not allowed the freedom they needed to provide growth to the rest of the economy. During the 1920s, governments tried to return the world to the “normalcy” that had prevailed before July 31, 1914, but failed. Germany and several other Eastern European countries sank into hyperinflation that wiped out investors. German bondholders and shareholders lost virtually everything they had during the hyperinflation of 1923. England’s attempt to return to the Gold Standard proved a failure leading to a recession and forcing Britain to leave the Gold Standard in 1931. The collapse of the Creditanstalt bank in Vienna in 1931 affected banks throughout Europe. The collapse of equity markets in the United States led to the regulation of securities in the United States by the SEC in 1934. After World War I, stock markets were based upon national capital markets. When the Austro-Hungarian empire broke up, new stock exchanges appeared in the capitals of each new country. After World War I, each country had its own stock exchange, but after World War II, many of these stock exchanges disappeared when Communism took over in Eastern Europe. The Nazis defaulted on their debts in the 1930s and restricted capital flows into security markets so available capital could be focused on rebuilding the German military. Capital could not flow from one country to another as had occurred before World War I. When World War II began stock exchanges were better prepared for war and few exchanges shut down. Instead, price controls limited trading in shares, as in Germany, and trading eventually ground to a halt. Britain nationalized the railways, the Bank of England, the steel industry and other companies after World War II. Similar nationalizations occurred in France and other European countries. Some stock exchanges never reopened in countries that went Communist. In Germany, the currency conversion of 1948 made shares in Deutsche mark worth 10% of their value in Reichsmark. After World War II, transports, utilities, finance and other heavy industry were regulated in the United States and nationalized in Europe. Nationalization removed those industries from stock markets in Europe and restricted their size in the United States. Because transports, utilities and banks were regulated in the United States, their profits were restricted and their capitalization was reduced. The Paris Stock Exchange was closed by strikes in April 1974 and March 1979, symbolizing that the conflict between capital and labor was more important than promoting capital markets. In the late 1940s, even more restrictions were placed on international capital flows. The IMF introduced a system of fixed exchange rates based upon the Dollar to replace the chaos that existed before World War II. The Bretton Woods agreements only worked by restricting capital flows across borders, so capital was raised domestically or not at all. After World War II, many of the industries in Europe were nationalized and the ratio of market capitalization to GDP shrank dramatically outside of the United States. By 1950, global market cap was equal to less than 25% of world GDP, and of this, the United States, United Kingdom, Canada and Australia represented about 80% of global market cap. Outside of the Anglo-American countries, equity markets had very little influence on the economy. European capitalization shrank because major portions of the economies were nationalized by the government.

The Fourth Era: The Return of Globalization

Although the date when Regulation and Nationalization replaced Globalization on July 31, 1914 is precise, the transition from Monopoly to Globalization between 1789 and 1815 and the return of Globalization between 1973 and 1990 are not so clearly dated. We will set the beginning of the Return of Globalization at 1981 when interest rates peaked and equities were in a bear market. Independent national financial markets no longer worked and the integration of global financial markets was seen as a solution to allocating capital more efficiently. One of the key beneficiaries of the return of Globalization was Asia. Japan and other Asian countries showed a dramatic rise in exports to the rest of the world and growth in their share of global market capitalization reflected this. The stock markets of Japan, Korea, Taiwan and Singapore illustrated to the rest of the world that stock markets could successfully allocate capital. Asian market capitalization was less than 5% of the world until the 1960s, but by the 1980s, Asia’s share of global market cap was greater than Europe’s, and by 1989 Asian countries represented almost half of global market capitalization. The Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges were established in 1991 and China’s share of global market cap began its inexorable rise. The rise of Asia is illustrated in Figure 4.

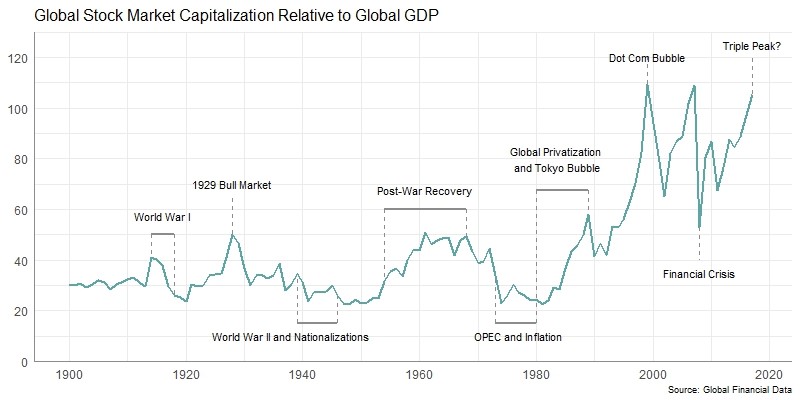

Although Bretton Woods and other post-war economic accords brought much-needed stability and recovery to the international economy, the global economy faltered in the 1970s. Keynesian policies were originally seen as a way of smoothing out the economic cycle, but by the 1970s, high inflation had pushed inflation up to double-digit levels in almost every country in the world. The economies of Communist countries failed even more than capitalist economies. After the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, stock markets were reestablished in St. Petersburg and other former Communist countries including China. European governments privatized industries that had been nationalized after World War II, and in the United States regulated industries were deregulated. This process began under President Carter in the United States. Deregulation affected banks, railways, telecommunications and utilities, the steel industry, airlines, and other infrastructure-related industries. Bretton Woods based international capital markets on the U.S. Dollar, but in 1973, floating exchange rates replaced fixed exchange rates. In the 1980s, capital controls were lifted and once again, capital could flow freely between different countries. The Big Bang in London reestablished London as the financial center of Europe. Europe pushed for a common market which would allow labor, goods and capital to travel freely in Europe and enable companies to gain economies of scale by operating across the European continent rather than being restricted to operations within one country. Information technology and biotechnology became the leading industries in the United States and other parts of the world. Money flowed into technology companies in the 1990s and at the height of the bubble in technology stocks in 1999, for the first time in history, global equity capitalization exceeded global GDP. This is illustrated in Figure 5 which shows not only the dramatic growth in the ratio of market cap to global GDP, but the increased volatility that has come with this growth.

Privatization was promoted by Thatcher in Britain and Reagan in the United States. In France, Francois Mitterand initially nationalized parts of the economy, but two years later reversed course and privatized both the industries he had nationalized as well as industries that had been nationalized before Mitterand was elected President. Industry had been owned by the state in Communist countries and once these countries allowed the market to allocate resources, the governments privatized state industries by providing shares in these companies to their citizens. Today, hundreds of millions of people depend upon the stock market for their retirement. Sovereign wealth funds have invested trillions into the stock market to provide money to their citizens in the future. These trends are unlikely to reverse. It would be hard to imagine the world returning to the regulated capital markets of the 1940s and 1970s. The changes that have occurred in financial markets during the twenty-first century have been driven by technology, not government deregulation. The Dot.com Bubble of the late 1990s pushed global market cap above global GDP for the first time in history. Virtual exchanges exist independent of any location. It seems unlikely that war, nationalization or regulation will push financial markets back to the condition they were in before 1981. It seems more likely that technology will push global markets into a new era in which multiple markets are replaced by a single market for all financial assets throughout the world. This would return the world to the globalized financial markets that existed before 1914.

The Fifth Era: Financial Singularity

Computer scientists talk about the possibility of a technological singularity, when the creation of artificial superintelligence could create computers that exceed human intelligence and lead mankind into a new era. There is a lot of debate about whether this will ever occur or could occur, but some scientists believe it is only a matter of time. We could also think of a future in which there is a financial market singularity, a point at which global financial markets become integrated into a single, 24-hour market that operates independently of national borders and exchanges. With the advent of artificial intelligence and blockchain, a financial singularity has become not only possible, but probable. The main question is not whether this will occur, but when it will occur and how. Equity markets are fully globalized today, and barring any dramatic change in the global political economy, they are likely to remain fully integrated for some time to come. Although there is always the threat of re-regulation of different parts of the economy, nationalization of entire industries seems unlikely. Nationalized firms would be unable to survive in the globalized world that exists today. Asia will continue to increase its share of global market capitalization at the expense of Europe. Today, financial markets are driven by technology which makes it easier and cheaper to integrate financial markets into a single market. The foreign exchange market is a global market that trades 24 hours a day. Money is digital and moves around the world on electronic networks. At some point in the future, equity and bond markets will trade 24 hours a day in a single market. How long it takes to reach that point depends upon technology and politics. Computers will enable markets to become more integrated in the future. Both artificial intelligence and blockchain will enable financial markets to move away from the exchange-based markets that exist today and be replaced by markets that never sleep and reside in the cloud. There is no reason why global financial markets shouldn’t become fully integrated in the near future just as regional stock exchanges have integrated into national exchanges in most of the countries in the world. What still needs to be done is for markets to move toward singularity. Politicians in Europe, America and Asia need to provide the institutional framework that will enable the financial singularity to exist. If politicians fail to create the conditions for integrating national markets into a single international market that operates 24 hours a day, markets will integrate independently of national exchanges. History has shown that existing exchanges rarely lead the way in introducing new technology. Electronic exchanges are born independently of existing exchanges. NASDAQ grew as a challenge to the NYSE and AMEX in 1971. Instinet, Island, Archipelago, BATS, the Investors Exchange and others grew independently of the major exchanges while dark pools trade hundreds of millions of shares daily. Yet, in all of these computerized changes, existing exchanges such as the NYSE was an adapter, not a disrupter, and has been forced to play technological catch-up. During the past 20 years, the NYSE has been behind the curve, following technological changes, not leading them, as its share of the trading of NYSE stocks has slowly declined. Twenty years ago, 80% of trades in NYSE-listed stocks were traded on the NYSE. Today only 30% of consolidated trades take place on the NYSE. More NYSE shares are traded through Nasdaq than on the NYSE, and about 40% of trading is off the exchanges in dark pools. If the stock market in the first half of the 20th Century was 1,000 floor traders trying to out-trade each other, and the second half of the century was 1,000 money managers trying to outsmart one another, the stock market of the 21st century may be 1,000 computer engineers trying to out-program one another. Over the past two centuries, exchanges have lost their advantage of providing price transparency, liquidity and timely execution at a minimal cost. Bonds, commodities and foreign currency have all migrated from exchanges to over-the-counter computers. Institutions trade between themselves and the retail market in shares is collapsing as index funds and ETFs continue to grow in popularity. The NYSE and other exchanges have lost their advantages in the market and their very existence is now in question. Given this, it is our prediction that the financial singularity will occur independently of efforts of existing exchanges to merge into a single market. We believe this will happen in the 2020s, but when and how, we do not know. But even when all this happens, and exchanges disappear, companies will still raise capital by issuing shares to the public, billions of people will still rely upon stocks for their investments, and we will still worry about whether the stock market will go up or go down tomorrow.

GFD's 100-share Index

Existing calculations of long-term stock market returns in the United States are based upon four primary sources: Smith and Cole (1803-1862), Macaulay (1857-1871) Cowles (1871-1928) and Standard and Poor’s (1928-2017). Unfortunately, these indices have major flaws in them that create biases that researchers have tolerated until now because no one has ever collected historical data on U.S. share prices, corporate actions (dividends and splits) and shares outstanding so accurate price and return indices could be calculated. The current S&P Composite includes data from the Cowles Indices from 1871 until 1927, the 90-share daily S&P Index from January 1928 until February 1957, the 500-share composite that excludes finance stocks until July 1976 and the all-sector 500-share index since July 1, 1976. Global Financial Data has collected data on all major United States exchanges going back to 1791 as well as data on over-the-counter shares since 1865. The data includes not only share price data, but information on corporate actions (dividends and splits) as well as shares outstanding. These data sources enable us to calculate cap-weighted price and return indices for the United States that accurately reflect what an investment in the 100 largest stocks each year would have produced for investors. GFD set up criteria for determining which stocks are included or excluded from its indices. GFD has followed these rules for inclusion: 1) There have to be at least 9 observations per year for each stock and there have to be at least two price changes during each year to warrant inclusion. Otherwise, the stock was excluded due to illiquidity. 2) Dividend data have to be available for each stock in order that both price and return indices can be calculated. A stock may not have paid a dividend during a particular year, but to be included, we had to know the company had passed on paying a dividend during that year. Any shares for which we were unable to find dividend information was excluded. 3) There had to be share outstanding information available so the stock could be included in a capitalization-weighted index 4) Only non-assessable shares were included. A stock was excluded if it imposed assessments on shareholders. Shares that were liquidating assets and were paying liquidating dividends were excluded as well. The index includes all shares that met these criteria from 1791 to 1824, the top 50 shares by capitalization are used from 1825 to1850 and the top 100 shares by capitalization from 1851 to 2017. Although GFD plans to calculate indices that include more than 100 shares in the future, we decided that because the index was capitalization-weighted, a 100-share index would track a 500-share index very closely. The graph below compares the performance of the S&P 100 (green line) and the S&P 500 (black line) between 1976 and 2018. The performance of the two is very similar. The S&P 500 did outperform the S&P 100 by 0.5% per annum, but the returns are close enough to show that a strong correlation exists between the top 100 shares and the top 500 shares. In 2017, the top 100 shares in the S&P 500 represented about 60% of the total capitalization of the S&P 500.

To choose which companies to include, shares were weighted by capitalization during the first month of each year and included if they were among the 100 largest shares in the United States. It was assumed that the stocks were held for the rest of the year, and in January of the next year, the same selection methodology was used to choose which shares to hold for the coming year. Each year, the list of the 100 largest companies was recalculated and a new list of stocks was introduced. For continuity purposes, if a stock missed a year, i.e. the stock was in the top 100 in 1914 and 1916, but not in 1915, the stock was included in the index in 1915 even though this put over 100 stocks in the index. Initially, there were less than 100 shares in the index because of a lack of companies that met the criteria outlined above. There were only 3 companies in 1791, 7 in 1800, 18 in 1810, 25 in 1820 and 50 in 1825. The index included 50 members through 1850 and beginning in 1851, there were 100 shares in the index. The chart below shows the sectoral composition of the GFD-100 index from 1800 until 2017 to cover the period before the introduction of the Cowles indices in 1871. However, the Smith and Cole indices have some major biases in them. The indices use a very limited number of companies, excluding, for example, the first and second Bank of the United States, which represented from 50% to 80% of the overall capitalization of the United States stock market. Consequently, Smith and Cole exclude over half of the U.S. stock market in their indices.

As can be seen, finance stocks (banks and insurance companies) represented over 95% of the capitalization until 1825. After 1825, the transportation sector grew, first with canals and then with railroads. By the 1840s, transports represented over half of the total capitalization, growing to 80% by the 1870s, then shrinking as industrials began to dominate the U.S. stock market. By 1900, industrial stocks represented about 40% of total capitalization with Energy stocks, primarily Standard Oil and its subsidiaries, representing a growing portion of total capitalization. It should be noted that Standard Oil of New Jersey and California (ExxonMobil and Chevron) weren’t included in the Cowles indices until 1918 when Standard Oil listed on the NYSE. By 1918, Standard Oil had grown tenfold in size to become the largest company in the world, yet was not included in any indices because it traded over-the-counter. And as we stated previously, no finance stocks were included in either the Cowles indices or the S&P indices until 1976. Therefore, we feel that the composition of stocks in the GFD indices are more representative of the stocks that were available to investors in the United States than any of the existing indices of United States stocks. To show how the GFD-100 index differs from existing indices of U.S. stocks we will compare the components and performance of the GFD-100 index and other indices.

Survivorship Bias in the Smith and Cole Indices

Currently, no index for U.S. stocks exists prior to 1802 when the Smith and Cole indices begin. Therefore, the GFD-100 index covers data that is currently unavailable from existing indices. The graph below compares the Cole and Smith indices (USCFALLM) with the GFD-100 index (GFUS100MPM) from 1802 until 1845 when Smith and Cole’s Bank and Insurance index was discontinued. As can be seen, the Smith and Cole index outperforms the GFD-100 index; however, in analyzing how the Smith and Cole indices were put together, we discovered that the superior performance was caused by the survivorship bias that Smith and Cole built into their indices.

In Walter B. Smith and Arthur H. Cole, Fluctuations in American Business, 1790-1860, Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Press, 1935, they provided calculations of stock market indices for Banks (1802-1820), Banks and Insurance (1815-1845) and Railroad (1834-1862) shares which have been used to cover the period before the introduction of the Cowles indices in 1871. However, the Smith and Cole indices have some major biases in them. The indices use a very limited number of companies, excluding, for example, the first and second Bank of the United States, which represented from 50% to 80% of the overall capitalization of the United States stock market. Consequently, Smith and Cole exclude over half of the U.S. stock market in their indices. For the dataset of bank stocks from 1802 until 1820, Smith and Cole collected data on 21 bank stocks, 9 insurance shares, 5 bridge and turnpike shares and 3 miscellaneous companies. Smith and Cole based their index on 7 bank stocks which existed during the entire 19-year period from 1802 until 1820, creating a survivorship bias. Banks such as the first Bank of the United States were excluded because they did not survive until 1820. Since Smith and Cole collected no data on shares outstanding, the index was calculated as a geometric mean of the underlying shares. The index is not cap-weighted even though it included only 7 banks. Because Smith and Cole collected no data on dividends, no return index was calculated. Scholars who have attempted to calculate total returns have calculated a dividend yield based upon the yield on government stocks. Jeremy Siegel in his book Stocks for the Long Run, uses a 6.4% dividend between 1802 and 1870. Smith and Cole collected data on 17 bank stocks, 5 canal stocks, 3 gas-light stocks, 19 insurance stocks, 27 rail, 6 miscellaneous and 17 Boston bank shares between 1815 and 1845. From these shares, they chose 6 bank shares and 1 insurance company for the Bank and Insurance index. Again, only stocks that survived the 30-year stretch between 1815 and 1845 were included, once again creating a survivorship bias. Finally, Smith and Cole calculated a railroad index that went from 1834 to 1862. Smith and Cole removed shares that either changed little or were erratic in their behavior. They broke up the data into 8 shares from1834 to 1853 and in several cases, because the data series were incomplete, they “spliced” together some of the series even though they admitted this was a statistical device of “questionable value.” Smith and Cole calculated two rail indices of 8 and 10 shares from 1834 to 1853 and a composite of 18 shares from 1853 to 1862. Finally, they calculated a chain-linked index of railway shares that covered 1834 to 1862 as well as some regional rail indices. A railway index of 25 shares calculated by Frederick R. Macaulay in The Movements of Interest Rates, Bond Yields and Stock Prices in the United States Since 1856, New York: National Bureau of Economic Research, 1938 was used to fill in the gap between 1862 and 1870. The performance of the rail indices is provided below. Although the GFD-100 and Smith and Cole Rail index take divergent paths, they both end up at the same levels over the 28-year period. The GFD Transports outperform the Smith and Cole Railway Index, especially in the 1850s, but the general pattern of their performance at any point in time is similar. The difference lies in the rate of return.

It is unfortunate that the Smith and Cole indices have been the sole source of returns for the United States before 1870. The problem with the Smith and Cole indices are several: 1) they use a limited number of stocks, 2) their selection process creates a survivorship bias that increases returns, 3) calculations are based upon the geometric mean of the shares rather than the capitalization of each share, 4) railway shares are spliced together to provide consistent coverage, and 5) no data on dividends was collected so no total returns could be calculated. As was discussed above, because of the survivorship bias that is inherent in the Cole and Smith indices, one would expect that their indices would outperform the other indices that lack a survivorship bias. The survivorship bias is particularly notable in the exclusion of the second Bank of the United States. After the bank lost its charter from the Federal government in 1836, Stephen Girard took over the bank and privatized it. The bank collapsed during the depression that followed the Panic of 1837, and Bank of the United States stock declined in value from 123 in January 1839 to 3.5 by December 1841. The bank’s capitalization fell from $42 million to $1 million. The GFD-100 index lost almost half of its value as a result. The chart below compares the Smith and Cole/Macaulay index with the GFD-100 index from 1802 until 1871. As can be seen, the survivorship bias enables the Smith and Cole/Macaulay index to outperform the GFD-100 during the entire period. From 1845 on, the Smith and Cole/Macaulay index includes no finance stocks and outperforms the GFD-100 even more. The combination of survivorship bias and exclusion of bank and insurance shares after 1845 causes the GFD-100 to underperform the Smith and Cole/Macaulay index. Because the GFD-100 includes more stocks and is cap-weighted, it provides a better representation of the return shareholders would have received before the introduction of the Cowles indices in 1871.

Limitations of the Cowles Indices

In the 1930s, Cowles created cap-weighted indices for the United States going back to 1871. The Commercial and Financial Chronicle published annual summaries of monthly high and low prices for stocks. The Cowles Commission collected data on shares outstanding and dividends in order to calculate cap-weighted price and total return indices for the United States. The Cowles indices included 44 shares in 1871, 75 in 1880, 88 in 1890, 102 in 1900, 126 in 1910, 243 in 1920 and 450 in 1930. The GFD-100 index included about 100 shares in each of those years. Although the Cowles indices are cap-weighted and include dividends, there are drawbacks to the Cowles indices. In calculating the indices, prices were based upon the average of the high and low prices for each month, not on the closing price of shares in each month. Although this factor affects the volatility of the indices, it should have a minimal impact on the long-term returns of the index. More importantly, the selection of stocks was limited to shares traded on the New York Stock Exchange. This means that bank and insurance shares as well as Standard Oil and other non-NYSE companies are completely excluded from the Cowles indices. Even though Standard Oil began trading in 1882, neither Standard Oil of New Jersey (ExxonMobil) nor of California (Chevron) was included in the Cowles indices until 1918 when they joined the NYSE. At the time, Standard Oil was the largest corporation in the world. The impact of excluding Standard Oil, banks and insurance companies is illustrated below.

Standard Oil (XOM – blue) clearly outperformed the other indices with finance stocks (GFUSBNKINSMPM – green) coming in second. Transports (GFUSTRANSMPM – black) did outperform the Cowles Indices (_SPXD – purple), but the Cowles indices provided the lowest return of the indices in the graph. The graph below looks at the sectoral composition of the Cowles/S&P Broad Composite index from 1871 to 1957 when it was discontinued in favor of the S&P 500. This sector chart can be compared with the sector chart of the GFD-100 provided above. As can be seen, the Cowles/S&P index is missing the finance sector and gives a lower weighting to the Energy sector than the GFD-100 sector chart. This absence is made up by the larger role of transportation (railroad) shares in the index until the 1920s.

The GFD-100 and the S&P 90/500

The S&P 90-share index was introduced on January 1, 1928. It is used as the basis for the S&P Composite through March 1, 1957 when the S&P 500 replaced the S&P 90. Both the GFD-100 and the S&P 90 use a similar number of shares between 1928 and 1957 and as the graph below shows, the two indices track each other very well. The S&P 500 was introduced on March 1, 1957 and excluded finance stocks until July 1, 1976 when 40 finance shares were included in the S&P 500. On April 6, 1988 exact sectoral balances were dropped and the number of industrial, utility, transportation and finance stocks was based purely upon market cap, not on fixed ratios for different sectors. The chart below compares the performance of the GFD-100 and the S&P 90/500 index between 1918 when Standard Oil and Chevron listed on the NYSE and 1976 when finance stocks were added to the index. The correlation between the two indices is strong with the GFD-100 providing a 5.1% annual return between 1918 and 1976 and the S&P Composite providing a 4.7% return during the same period. Although we found reasons for the difference in the performance of the GFD-100 and the Smith and Cole/Cowles indices between 1802 and 1918, the similarity in composition between the GFD-100 and the S&P Indices has generated quite similar returns between 1918 and 1976.

Total Returns

Until now, we have only looked at the return to the price indices for the GFD-100 and the S&P Composite. Of course, shareholders receive dividends in addition to capital gains and historically, shareholders have received a higher return from dividends than from capital gains. Until now, no one has ever measured the dividends shareholders received before 1871. GFD’s calculations show that before 1871, U.S. shareholders on average received no capital gains. This means that 100% of shareholder return came from dividends. GFD has collected historical data on the dividends that were paid by thousands of companies in order that we could accurately calculate the dividends that shareholders received. A comparison of the yields on the S&P Cowles Composite and the GFD-100 is provided below. You can generally observe that the dividend yield declined between 1791 and 1820, rose from 1820 until 1870, then declined for the rest of the 1800s. The dividend yield shows similar behavior in the GFD-100 and the S&P Composite between 1871 and 2017. The dividends for the S&P Composite appear to be more volatile than the yields on the GFD-100 between 1871 and 1980. The reason for this lies in the different methodology used to calculate the dividend yield. S&P/Cowles collected data on annual dividends through 1935 and quarterly thereafter. The S&P dividend yield was calculated by dividing the annual dividends that were “paid” to shareholders by the price of the S&P Composite. Consequently, a large decline or rise in the S&P Composite index caused a spike in the dividend yield. Data for the GFD-100 dividend yield is calculated on an ongoing basis from month to month when the dividends are “paid” to the component companies on the ex-date, reducing the volatility in the dividend yield. Nevertheless, the dividend yield of the GFD-100 and the S&P Cowles Composite follow each other fairly closely. With this dividend data, we can calculate the total return to U.S. stocks over the entire period covered. No estimates based upon the yield on government bonds is needed. The total return from the GFD-100 and the S&P Composite are illustrated below. As can be seen, over the long-term, the differences between the two indices is small. The Smith/Cole/Cowles data outperform the GFD-100 in the early 1800s because of the survivorship bias inherent in the Smith and Cole data. However, the exclusion of over-the-counter shares (Standard Oil and finance stocks) by Cowles between 1871 and 1918 allows the GFD-100 to “catch up” with the Composite data. The two indices then track each other closely from 1918 until 1976 when S&P introduced bank and insurance shares into the S&P 500 Composite.

We can provide actual data on the total returns to the two indices in order that the two sets of indices can be compared directly. The table below shows the returns of the GFD-100 and the S&P Composite between 1802 and 2017. Annual capital gains for the GFD data and the S&P data are provided in the first two columns. Total Returns including reinvested dividends are provided in the next two columns and the dividends that were paid are compared in the last two columns. The returns are very similar over the 215 years for which both indices have data with capital gains of 3.57% per annum for the GFD-100 and 3.46% for the Cowles/S&P Composite. After dividends are added and total returns are calculated, similar numbers result. The GFD-100 provided a total return of 8.75% per annum and the Smith/Cole/Cowles/S&P Composite provided an 8.38% total return between 1802 and 2017. The dividends we interpolated between 1802 to 1870 was calculated as the yield on government bonds plus 1% yielding an annual dividend of 5.76%. If the dividend yield of 6.42% that we actually calculated between 1802 and 1870 were used, the total return to the S&P Composite would equal 8.67% between 1802 and 2017 which is close to the GFD-100 annual return of 8.75%. The period from 1802 until 2017 is also divided into a pre-Cowles period from 1802 until 1870 when Smith and Cole/Macaulay were the only source for indices, the period from 1871 to 1918 when Standard Oil was excluded from the index, and 1918 until 1976 when S&P calculated the index, but excluded finance shares.

Table 1 Comparison of Returns to GFD-100 and Cowles/S&P Composite

| SPX | GFD | SPX | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period | GFD Nominal | Nominal | GFD TR | SPX TR | Dividends | Dividends |

| 1802-1870 | -0.03 | 1.33 | 6.39 | 7.17 | 6.42 | 5.76 |

| 1871-1918 | 2.15 | 0.93 | 7.75 | 5.88 | 5.48 | 4.9 |

| 1918-1976 | 5.2 | 4.82 | 9.63 | 9.9 | 4.21 | 4.84 |

| 1802-1976 | 2.19 | 2.36 | 7.79 | 7.67 | 5.48 | 5.19 |

| 1802-2017 | 3.57 | 3.46 | 8.75 | 8.38 | 5 | 4.76 |

| 1791-2017 | 3.32 | 8.54 | 5.05 |

A decade-by-decade comparison of the return to stocks in the GFD-100, bonds in GFD’s U.S. Bond Index, bills in GFD’s US Bill Index and the equity-risk premium is provided below.

Decade-by-Decade Returns to Stocks, Bonds and Bills in the United States

| Decade | Stock Price | Stock Return | Dividends | Bonds | Cash | Equity Premium |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1792-1799 | -3.7 | 2.67 | 6.61 | -0.15 | 5.75 | -2.91 |

| 1800-1809 | 1.35 | 8.01 | 6.57 | 6.03 | 4.96 | 2.91 |

| 1810-1819 | -4.35 | 1.59 | 6.21 | 7.42 | 4.99 | -3.24 |

| 1820-1829 | 0.53 | 5.82 | 5.26 | 5.01 | 3.66 | 2.08 |

| 1830-1839 | -0.95 | 5 | 6.01 | 0.44 | 4.51 | 0.47 |

| 1840-1849 | -0.8 | 6.12 | 6.98 | 6.97 | 4.94 | 1.12 |

| 1850-1859 | -0.58 | 6.65 | 7.27 | 4.67 | 5.01 | 1.56 |

| 1860-1869 | 4.62 | 12.45 | 7.48 | 9.28 | 4.97 | 7.13 |

| 1870-1879 | 2.04 | 8.97 | 6.79 | 5.52 | 3.82 | 4.96 |

| 1880-1889 | 1.19 | 6.27 | 5.02 | 4.16 | 3.01 | 3.16 |

| 1890-1899 | 4.05 | 9.45 | 5.19 | 4.57 | 2.13 | 7.17 |

| 1900-1909 | 6.25 | 11.23 | 4.69 | 0.76 | 3.01 | 7.98 |

| 1910-1919 | -0.69 | 5.5 | 6.23 | 2.22 | 2.62 | 2.81 |

| 1920-1929 | 8.72 | 14.44 | 5.26 | 5.53 | 3.5 | 10.57 |

| 1930-1939 | -3.48 | 0.5 | 4.12 | 6.32 | 0.27 | 0.23 |

| 1940-1949 | 3.43 | 8.21 | 4.62 | 2.25 | 0.58 | 7.59 |

| 1950-1959 | 13.67 | 18.3 | 4.07 | 0.70 | 2.16 | 15.80 |

| 1960-1969 | 3.82 | 6.83 | 2.90 | 1.28 | 4.4 | 2.33 |

| 1970-1979 | 2.14 | 6.12 | 3.90 | 4.09 | 6.71 | -0.55 |

| 1980-1989 | 12.94 | 18.14 | 4.60 | 15.54 | 7.96 | 9.43 |

| 1990-1999 | 19.78 | 22.65 | 2.40 | 7.20 | 4.52 | 17.35 |

| 2000-2009 | -1.66 | 0.16 | 1.85 | 5.42 | 2.25 | -2.04 |

| 2010-2017 | 7.67 | 10.06 | 2.22 | 3.67 | 0.21 | 9.83 |

| Average | 3.30 | 8.48 | 5.06 | 4.73 | 3.74 | 4.60 |

Conclusion

Although the overall returns between 1802 and 2017 do not differ significantly between the GFD-100 and Cowles/S&P Composite, there are several advantages in using the GFD-100 as the benchmark for long-term historical data for the United States stock market rather than the Cowles/S&P Composite. 1. The GFD-100 uses shares that traded on all United States exchanges and over-the-counter from 1791 until 2017. The Cowles/S&P Composite is limited to the New York Stock Exchange before 1972. Finance companies that traded OTC and companies such as Standard Oil which traded OTC for several decades before moving to the NYSE are included in the GFD-100, but excluded from Cowles/S&P. 2. The GFD-100 uses shares from all sectors, including finance, from 1791 until 2017. The Cowles/S&P Composite only includes finance shares beginning in 1976 and ignores the finance sector before 1976. 3. The GFD-100 includes accurate data on dividends from 1791 to 2017. The Cowles/S&P Composite only calculated dividends from 1871 until 2017. There is no inclusion of dividends before 1871 in the Cowles/S&P Composite because no data on dividends were collected. Consequently, existing indices are missing 80 years of dividend data. 4. The GFD-100 is capitalization weighted from 1791 until 2017. The Cowles/S&P is cap-weighted from 1871 until 2017 and includes no capitalization weighting before 1871. 5. The Smith and Cole bank indices that cover the period from 1802 until 1845 suffer from survivorship bias. Banks were chosen for the indices based upon their longevity, not on their size or liquidity. The GFD-100 components are chosen based upon their market capitalization. The largest companies are chosen during each January and are “held” in the portfolio for the rest of the year when a new portfolio is organized for the coming year. 6. The Smith and Cole indices are based upon a very limited population of six to eighteen companies per year from 1802 until 1862. The GFD-100 includes 50 companies from 1825 until 1850 and 100 companies from 1851 using a broader population of shares. 7. The GFD-100 uses a consistent methodology from 1791 until 2017. The Cole and Smith/Macaulay/Cowles/S&P Index uses different methodologies. The data that are used to put together the composite are collected from four different sources and chain-linked together in an uncertain pattern. During the periods of time when different indices exist, choosing different indices generates different rates of return. Overall, the GFD-100 provides a superior benchmark stock index. Because of its greater accuracy, we would encourage financial historians to use the GFD-100 for their analysis of long-term trends in the stock market in the United States.

This month the world is marking the 100th anniversary of the end of World War I which officially ended at 11 am on November 11, 1918. Few people, however, have talked about the impact of the Great War on financial markets, both during and after the war was over. Global stock markets closed when World War I began and the globalized economy which existed on July 31, 1914 didn’t return for 75 years.

Before World War I began, the world’s financial markets were integrated. The gold standard fixed exchange rates between different countries. Russian bonds traded on the bourses of St. Petersburg, Berlin, Paris, Amsterdam, London, Vienna and New York simultaneously as did South Africa mining and other shares. The world’s financial markets were truly globalized with capital flowing freely from one country to another. It would take over 75 years for globalization to return to the world’s financial markets once the war began.

When World War I began on July 31, 1914, the immediate impact was the closure of stock exchanges throughout the world. There was a fear that shareholders would sell stock to raise capital and repatriate their money. Share prices began to collapse and the only way to prevent a panic was to close stock exchanges and prohibit shares from being sold. By August 1, virtually every stock exchange in the world had closed. Some exchanges opened later in 1914, but some such as the Berlin Stock Exchange, did not reopen until 1917. St. Petersburg reopened in 1917, but closed soon after as a result of the October Revolution. Other exchanges, such as Paris and London, reopened in a few months, but with restrictions on the price shares could be sold at. Even if you were able to sell shares, foreign exchange restrictions prevented shareholders from repatriating capital.

The government in each country was mainly concerned about funding the war. Restrictions were placed on issuing new shares and each country issued large amounts of government bonds to fund the war. Citizens were encouraged to buy war bonds to cover the costs of the war. The needs of capital markets were considered secondary.

To see the impact of World War I on global stock markets, we have divided countries into three groups, combatants (Great Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Belgium), neutral European countries (Spain, Denmark, Switzerland, Sweden, the Netherlands and Norway) and non-European countries (United States, Australia, South Africa, Japan, Canada). Each of these groups was affected differently by the onset of World War I and its aftermath.

Generally speaking, the stock markets of combatants did poorly during World War I as is illustrated below. Although the share markets of those countries went down slightly during the war, this understates the extent of the damage to shareholders because all of these countries suffered inflation which reduced the real value of their stock markets. Governments encouraged investors to buy government bonds, not shares and the performance of each stock market reflects this.

It is interesting to contrast the behavior of the stock markets of the victors after the war (France, Belgium, Great Britain) with the loser Germany. France’s stock market behaved the best of the five after World War I while the German stock market, primarily as a result of the hyperinflation in 1923 and its closure during the 1930s, showed the worst performance. Germany suffered economic and political turmoil after their defeat in World War I and the stock market shows this.

This month the world is marking the 100th anniversary of the end of World War I which officially ended at 11 am on November 11, 1918. Few people, however, have talked about the impact of the Great War on financial markets, both during and after the war was over. Global stock markets closed when World War I began and the globalized economy which existed on July 31, 1914 didn’t return for 75 years.

Before World War I began, the world’s financial markets were integrated. The gold standard fixed exchange rates between different countries. Russian bonds traded on the bourses of St. Petersburg, Berlin, Paris, Amsterdam, London, Vienna and New York simultaneously as did South Africa mining and other shares. The world’s financial markets were truly globalized with capital flowing freely from one country to another. It would take over 75 years for globalization to return to the world’s financial markets once the war began.

When World War I began on July 31, 1914, the immediate impact was the closure of stock exchanges throughout the world. There was a fear that shareholders would sell stock to raise capital and repatriate their money. Share prices began to collapse and the only way to prevent a panic was to close stock exchanges and prohibit shares from being sold. By August 1, virtually every stock exchange in the world had closed. Some exchanges opened later in 1914, but some such as the Berlin Stock Exchange, did not reopen until 1917. St. Petersburg reopened in 1917, but closed soon after as a result of the October Revolution. Other exchanges, such as Paris and London, reopened in a few months, but with restrictions on the price shares could be sold at. Even if you were able to sell shares, foreign exchange restrictions prevented shareholders from repatriating capital.

The government in each country was mainly concerned about funding the war. Restrictions were placed on issuing new shares and each country issued large amounts of government bonds to fund the war. Citizens were encouraged to buy war bonds to cover the costs of the war. The needs of capital markets were considered secondary.

To see the impact of World War I on global stock markets, we have divided countries into three groups, combatants (Great Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Belgium), neutral European countries (Spain, Denmark, Switzerland, Sweden, the Netherlands and Norway) and non-European countries (United States, Australia, South Africa, Japan, Canada). Each of these groups was affected differently by the onset of World War I and its aftermath.

Generally speaking, the stock markets of combatants did poorly during World War I as is illustrated below. Although the share markets of those countries went down slightly during the war, this understates the extent of the damage to shareholders because all of these countries suffered inflation which reduced the real value of their stock markets. Governments encouraged investors to buy government bonds, not shares and the performance of each stock market reflects this.

It is interesting to contrast the behavior of the stock markets of the victors after the war (France, Belgium, Great Britain) with the loser Germany. France’s stock market behaved the best of the five after World War I while the German stock market, primarily as a result of the hyperinflation in 1923 and its closure during the 1930s, showed the worst performance. Germany suffered economic and political turmoil after their defeat in World War I and the stock market shows this.