Events in Time Anniversaries: May 2020

25 years ago: May 1995 S&P 500: 533.40 (vs. 3044.31 in 05/2020) 10-year U.S. Government Bond Yield: 6.30% (vs. 0.65% in 05/2020) Gold: $384.30 (vs. $1728.70 in 05/2020) Oil: $18.875 (vs. $35.57 in 05/2020) GBP/USD: 1.586 (vs. 1.2346 in 05/2020) US GDP: $7,522 billion (vs. $21,534 billion in 03/2020) US Population: 266 million (vs. 331 million in 2020) 05/02/1995: During the Croatian War of Independence, Serb forces fire cluster bombs at Zagreb, killing seven and wounding over 175 civilians. 05/11/1995: More than 170 countries extend the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty indefinitely and without conditions. 05/12/1995: Operation Flash: The Croatian Army launched an offensive which would reconquer the territory of the former Western Slavonia in Krajina. 05/13/1995: Alison Hargreaves, a 33-year-old British mother, became the first woman to conquer Everest without oxygen or the help of sherpas. 05/17/1995: Jacques Chirac began his term as president of France. Alain Juppe (Rally for the Republic) became Prime Minister of France 05/18/1995: Shawn Nelson, 35, steals a tank from a National Guard Armory in San Diego, destroying cars and other property and is shot to death by police after immobilizing the tank. 05/23/1995: The first version of the Java programming language is released. 05/28/1995: The Russian town of Neftegorsk is hit by a 7.6 magnitude earthquake that kills at least 2,000 people, half of the total population. 50 years ago: May 1970 S&P 500: 76.55 (vs. 3044.31 in 05/2020) 10-year U.S. Government Bond Yield: 7.95% (vs. 0.65% in 05/2020) Gold: $35.45 (vs. $1728.70 in 05/2020) Oil: $3.21 (vs. $35.57 in 05/2020) GBP/USD: 2.4023 (vs. 1.2346 in 05/2020) US GDP: $1,051 billion (vs. $21,534 billion in 03/2020) US Population: 209 million (vs. 331 million in 2020) 05/01/1970: Protests erupt in Seattle, following the announcement by U.S. President Richard Nixon that U.S. Forces in Vietnam would pursue enemy troops into Cambodia, a neutral country. 05/04/1970: Kent State shootings: the Ohio National Guard, sent to Kent State University after disturbances in the city of Kent the weekend before, opens fire killing four unarmed students and wounding nine others. The students were protesting the United States' invasion of Cambodia. 05/08/1970: The Hard Hat Riot occurs in the Wall Street area of New York City as blue-collar construction workers clash with demonstrators protesting the Vietnam War. 05/09/1970: In Washington, D.C., 75,000 to 100,000 war protesters demonstrate in front of theWhite House. 05/11/1970: The Lubbock Tornado, aF5tornado, hits Lubbock, Texas, killing 26 and causing $250million in damage. 05/15/1970: ASE began implementing a computer system to route odd-lot orders directly from member-firm order rooms to posts on trading floor. Philip Lafayette Gibbs and James Earl Green are killed at Jackson State University by police during student protests. 05/31/1970: The Ancash earthquake causes a landslide that buries the town of Yungay, Peru; more than 47,000 people are killed. 100 years ago: May 1920 S&P 500: 7.94 (vs. 3044.31 in 05/2020) 10-year U.S. Government Bond Yield: 5.58% (vs. 0.65% in 05/2020) Gold: $20.67 (vs. $1728.70 in 05/2020) Oil: $6.10 (vs. $35.57 in 05/2020) GBP/USD: 3.87 (vs. 1.2346 in 05/2020) US GDP: $84 billion (vs. $21,534 billion in 03/2020) US Population: 106.46 million (vs. 331 million in 2020) 05/02/1920: The first game of the Negro National League baseball is played in Indianapolis. 05/05/1920: Authorities arrest Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti for alleged robbery and murder. 05/07/1920: Treaty of Moscow: Soviet Russia recognizes the independence of the Democratic Republic of Georgia only to invade the country six months later. Kiev Offensive: Polish troops led by Jzef Pisudski and Edward Rydzmigy and assisted by a symbolic Ukrainian force capture Kiev only to be driven out by the Red Army counter-offensive a month later. 05/15/1920: First U.S. Labor Bank opened in Washington, D.C. 05/20/1920: Montreal, Quebec radio station XWA broadcasts the first regularly scheduled radio programming in North America. Venustiano Carranza, President of Mexico was assassinated. 05/21/1920: Conference of British and French Premiers at Lympne. Scheme for abolition of dual control of the Stock Exchange published. 200 years ago: May 1820 S&P 500/GFD US-100: 1.573 (vs. 3044.31 in 05/2020) 10-year U.S. Government Bond Yield: 4.412% (vs. 0.65% in 05/2020) Gold: $19.39 (vs. $1728.70 in 05/2020) GBP/USD: 4.44 (vs. 1.2346 in 05/2020) US GDP: $727 million (vs. $21,534 billion in 03/2020) US Population: 9.6 million (vs. 331 million in 2020) 05/03/1820: At Kerikeri, Reverend John Butler uses a plough for the first time in the country. 05/11/1820: HMS Beagle, the ship that will take Charles Darwin on his scientific voyage, is launched. 05/15/1820: Revolution in Naples. © 2020 Global Financial Data. Please feel free to redistribute this Events-in-Time Chronology and credit Global Financial Data as the source.Events in Time Anniversaries: April 2020

25 years ago: April 1995

S&P 500: 514.71 (vs. 2783.36 in 04/2020) 10-year U.S. Government Bond Yield: 7.07% (vs. 0.63% in 04/2020) Gold: $389.75 (vs. $1718.65 in 04/2020) Oil: $20.355 (vs. $19.96 in 04/2020) GBP/USD: 1.612 (vs. 1.2488 in 04/2020) US GDP: $7,455 billion (vs. $21,734 billion in 12/2019) US Population: 266 million (vs. 329 million in 2019) 04/07/1995: First Chechen War: Russian paramilitary troops begin a massacre of civilians in Samashki, Chechnya. 04/13/1995: The Bank of Japan cut its discount rate by 3/4 percentage point to a low of 1%. 04/18/1995: A bomb rocks a federal building in Oklahoma City, killing 168 people and injuring more than 500. 04/30/1995: U.S. President Bill Clinton becomes the first President to visit Northern Ireland.

50 years ago: April 1970

S&P 500: 81.52 (vs. 2783.36 in 04/2020) 10-year U.S. Government Bond Yield: 7.82% (vs. 0.63% in 04/2020) Gold: $35.85 (vs. $1718.65 in 04/2020) Oil: $3.21 (vs. $19.96 in 04/2020) GBP/USD: 2.405 (vs. 1.2488 in 04/2020) US GDP: $1,036 billion (vs. $21,734 billion in 12/2019) US Population: 209 million (vs. 329 million in 2019) 04/01/1970: President Richard Nixon signs the Public Health Cigarette Smoking Act into law, requiring the Surgeon General's warnings on tobacco products and banning cigarette advertisements on television and radio in the United States, starting on January 1, 1971. 04/02/1970: Institutions dumped glamor stocks. Market concerned about spreading strikes by Teamsters, Mid-East turmoil, enemy action in Vietnam, Cambodia, first quarter earnings. 04/10/1970: Paul McCartney announces that he is leaving The Beatles for personal and professional reasons. 04/13/1970: AT&T's huge rights offering began. Company's warrants became listed, after NYSE lifted a 51-year ban on such listings. An oxygen tank aboard Apollo 13 explodes, putting the crew in great danger and causing major damage to the spacecraft while en route to the Moon. 04/15/1970: During the Cambodian Civil War, massacres of the Vietnamese minority results in 800 bodies flowing down the Mekong River into South Vietnam. 04/24/1970: Dow Industrials had biggest drop in 9 months. During this month Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette blazed trail to public ownership with first offering of a NYSE member firm. 04/29/1970: United States and South Vietnamese forces invade Cambodia to hunt Viet Cong.

100 years ago: April 1920

S&P 500: 8.27 (vs. 2783.36 in 04/2020) 10-year U.S. Government Bond Yield: 5.28% (vs. 0.63% in 04/2020) Gold: $20.67 (vs. $1718.65 in 04/2020) Oil: $6.10 (vs. $19.96 in 04/2020) GBP/USD: 3.826 (vs. 1.2488 in 04/2020) US GDP: $84 billion (vs. $21,734 billion in 12/2019) US Population: 106.46 million (vs. 329 million in 2019) 04/03/1920: 21 different Freikorps units, under the command of General Baron Oskar von Watter, annihilate the Ruhr Communist uprising in five days; thousands killed. 04/15/1920: Rise in French Bank rate from 5 to 6 percent; it had stood at 5 percent since August 20, 1914. Italian Bank rate also raised from 5 to 5 1/2 percent. Franc at 61.50 to 1. Two security guards are murdered during a robbery in South Braintree, Massachusetts. Anarchists Sacco and Vanzetti would be convicted of and executed for the crime, amid much controversy. 04/23/1920: The Grand National Assembly of Turkey(TBMM) is founded in Ankara, Turkey. It denounces the government of Sultan Mehmed VIand announces the preparation of a temporary constitution. 04/26/1920: The Khorezm People's Soviet Republic was established on the territory of the defunct Khanate of Khiva. 04/28/1920: With the Azerbaijani capital Baku under Eleventh Army occupation, the parliament agreed to transfer power to the Communist government of the Azerbaijan SSR.

200 years ago: April 1820

S&P 500/GFD US-100: 1.554 (vs. 2783.36 in 04/2020) 10-year U.S. Government Bond Yield: 4.615% (vs. 0.63% in 04/2020) Gold: $19.39 (vs. $1718.65 in 04/2020) GBP/USD: 4.44 (vs. 1.2488 in 04/2020) US GDP: $727 million (vs. $21,734 billion in 12/2019) US Population: 9.6 million (vs. 329 million in 2019) 04/08/1820: The Venus de Milo is discovered on the Aegean island of Melos. 04/12/1820: Alexander Ypsilantisis declared leader of Filiki Eteria, a secret organization to overthrow Ottoman rule over Greece. © 2020 Global Financial Data. Please feel free to redistribute this Events-in-Time Chronology and credit Global Financial Data as the source.

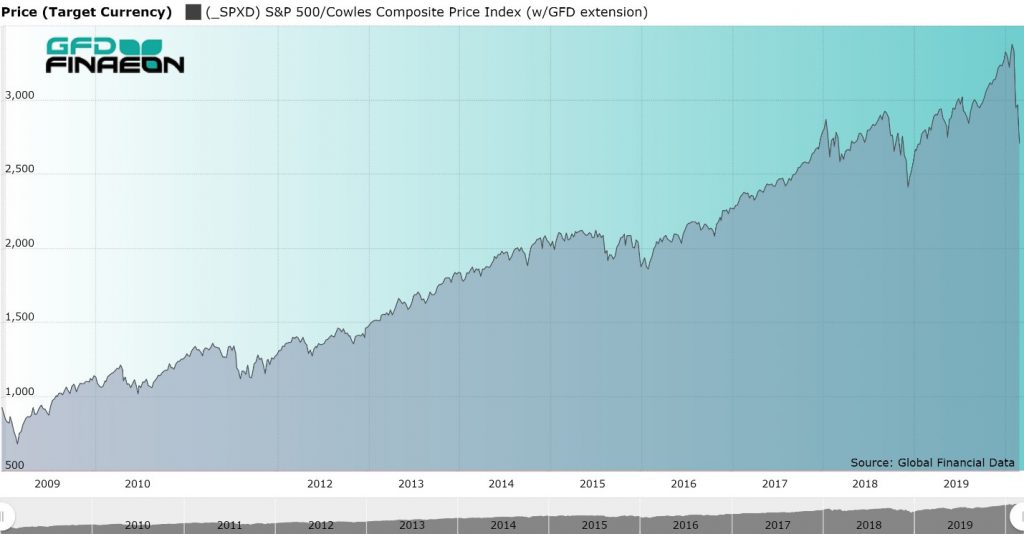

Figure 1. S&P 500, 2009 to 2020

Raging Bull to Roaring Bear

What is interesting about this bear market is how quickly it hit and how sharply markets throughout the world dropped in response to the Coronavirus epidemic. There was no gradual spread of this financial pandemic. It hit all the world’s stock markets severely and simultaneously.

Information of all the bull and bear markets that have affected the American stock market since 1792 and is provided in Table 1. For each market we have provided the date when the bull or bear market hit its top or bottom, the value of the index and the percentage decline in the bear market or percentage rise in the bull market.

Bear Stats are In

By our calculation, there have been twenty-four bull and bear markets since 1792 with four occurring in the 1800s, seventeen in the 1900s and three in the 2000s. The worst decline was the 1929-1932 bear market during which the Dow Jones Industrials declined by 89%. The longest bear market lasted from 1792 until 1843. The strongest bull market occurred between 1974 and 1987 when the market rose by 442%. The two previous bear markets in this century both had declines of 50% in 2000-2002 and 2007-2009.

| Date | Value | Change | Date | Value | Change | Cause |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01/02/1792 | 4.516 | |||||

| 01/31/1843 | 1.497 | -66.85 | 08/31/1853 | 2.584 | 72.61 | Panic of 1837 |

| 10/31/1857 | 1.712 | -33.75 | 07/30/1864 | 4.092 | 139.02 | Panic of 1857 |

| 10/31/1873 | 2.682 | -34.46 | 05/31/1881 | 5.189 | 93.48 | End of Civil War, Panic of 1873 |

| 01/31/1885 | 3.394 | -34.59 | 6/17/1901 | 8.53 | 123.88 | Long Depression |

| 11/9/1903 | 5.85 | -31.42 | 10/9/1906 | 10.23 | 74.87 | Rich Man's Panic |

| 11/15/1907 | 6.10 | -40.37 | 11/19/1909 | 10.6 | 73.77 | San Francisco |

| 10/31/1914 | 6.63 | -37.45 | 11/20/1916 | 10.55 | 59.13 | World War I |

| 12/19/1917 | 6.00 | -43.13 | 7/16/1919 | 9.64 | 60.67 | Fear of Entering War |

| 8/24/1921 | 6.26 | -35.06 | 9/7/1929 | 31.86 | 408.95 | Post-WW I Recession |

| 7/8/1932 | 4.41 | -86.16 | 9/7/1932 | 9.31 | 111.11 | Great Depression |

| 2/27/1933 | 5.53 | -40.60 | 7/18/1933 | 12.2 | 120.61 | Bank Holidays |

| 3/14/1935 | 8.06 | -33.93 | 3/10/1937 | 18.68 | 131.76 | Depression Fears |

| 3/31/1938 | 8.5 | -54.50 | 11/9/1938 | 13.79 | 62.24 | Recession of 1937 |

| 4/28/1942 | 7.47 | -45.83 | 5/29/1946 | 19.25 | 157.70 | World War II approaches |

| 6/13/1949 | 13.55 | -29.61 | 8/2/1956 | 49.75 | 267.16 | Post-WWII Recession |

| 10/22/1957 | 38.98 | -21.65 | 12/12/1961 | 72.64 | 86.35 | Sputnik |

| 6/26/1962 | 52.32 | -27.97 | 2/9/1966 | 94.06 | 79.78 | Steel Strike, Kennedy Panic |

| 10/7/1966 | 73.2 | -22.18 | 1/5/1973 | 119.87 | 63.76 | Viet Nam |

| 10/3/1974 | 62.28 | -48.04 | 8/25/1987 | 337.89 | 442.53 | OPEC Embargo |

| 12/4/1987 | 221.24 | -34.52 | 7/16/1990 | 369.78 | 67.14 | 1987 Crash |

| 10/17/1990 | 294.51 | -20.36 | 3/24/2000 | 1527.46 | 418.64 | Iraq War |

| 10/9/2002 | 776.77 | -49.15 | 10/9/2007 | 1565.15 | 101.49 | Internet Bubble, 9/11 |

| 3/9/2009 | 676.53 | -56.78 | 2/19/2020 | 3386.15 | 400.52 | Financial Recession |

| 3/12/2020 | 2236.70 | -33.95 | Coronavirus |

Table 1. Bear Markets in the United States, 1792 to 2020

The question is, how much more is the stock market likely to fall before we reach a bottom? Will this be a short-lived bear market as occurred in 1987 and 1990 or a more extended bear market as occurred in 2000-2002 and 2007-2009? We certainly hope that the restrictions on travel, reduction in large gatherings, encouragement for social distancing and self-quarantine will be effective in reducing the spread of Covid-19 throughout the United States and the rest of the world so the stock market can regain its losses, build a bottom and begin another bull market. Afterall, who doesn’t love the raging bull?