The graph below illustrates the history of global stock markets by capitalization from 1900 to 2018. The graph uses the World Federation of Exchanges definitions and divides the world into three groups: the Americas which includes both North and South America, Europe/Africa/Middle East, and Asia and Oceania. It shows how each continent’s share of global Stock market capitalization has changed over time. The Americas represented the majority of global market capitalization during the past 120 years, but the most obvious trend over time is the decline of Europe and the rise of Asia.

The graph below illustrates the history of global stock markets by capitalization from 1900 to 2018. The graph uses the World Federation of Exchanges definitions and divides the world into three groups: the Americas which includes both North and South America, Europe/Africa/Middle East, and Asia and Oceania. It shows how each continent’s share of global Stock market capitalization has changed over time. The Americas represented the majority of global market capitalization during the past 120 years, but the most obvious trend over time is the decline of Europe and the rise of Asia.

The World in 1900

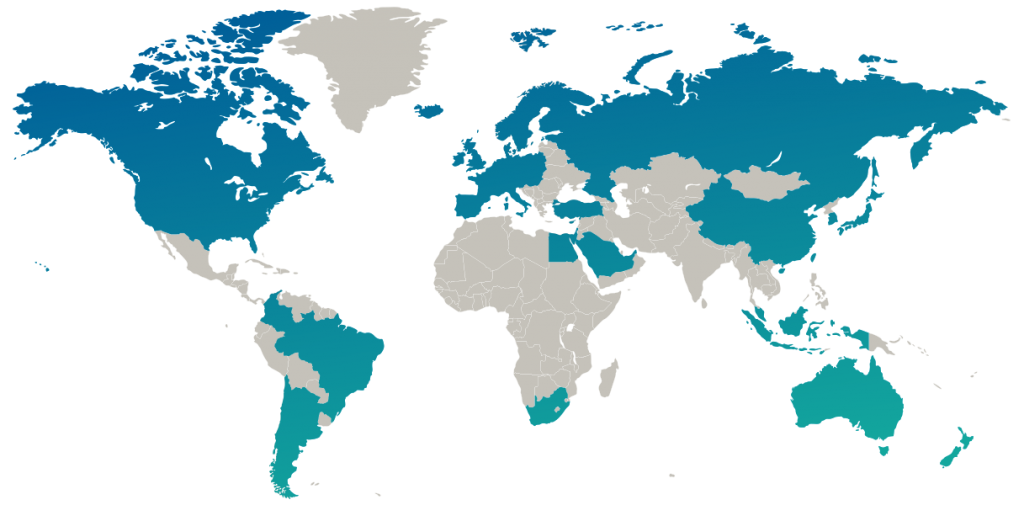

In 1900, Europe dominated global stock markets. Europe represented about 68% of global stock market capitalization, the Americas around 30% and Asia only 2%. By 2018, Asia had become the second largest continent by capitalization. The Americas represented 44% of global stock market capitalization, Asia 34% and Europe 22%. Europe dominated global financial markets in 1900 and London was at the center of European finance. European countries were on a gold standard that linked all currencies to each other at fixed exchange rates and money flowed freely between European countries. Europe funded railroads, banks, utilities and other companies in Europe and the rest of the world. American railroads were traded on all the major stock exchanges in Europe. In 1900, there were very few stock markets anywhere in Asia, in part because many countries were European colonies. There were stock markets in Shanghai, Tokyo and Hong Kong, and limited trading in Australia, New Zealand and India; however, the value of Asian securities that were traded in London exceeded trading in Asia. Companies that operated in French Indochina, the Netherlands Indies, Malaysia and other European colonies listed in Europe, not on local exchanges. European capital markets had more resources available for investment than Asian capital markets. Until the 1970s, Asia represented a very small portion of global stock market capitalization. The majority of global stock market capitalization was located in North America. Between 1900 and 1970, the Americas grew in size while Europe shrank. The primary causes of this transformation were World War I, World War II and the nationalization of European industry.The Decline of Europe

In 1914, Europe represented about 61% of global market capitalization and the Americas 37%. Capital flowed freely from one European country to another. Russia issued bonds payable in Russian Rubles, British Pounds, French Francs, German Marks, United States Dollars, Dutch Guilder and Austrian Crowns. It was truly a globalized world. But on August 1, 1914, all European and American stock markets closed. The flow of capital between countries stopped and stock markets in Berlin and St. Petersburg remained closed until 1917. The St. Petersburg stock market closed for the next 75 years when the Russian Revolution overthrew the Tsar. With Europe recovering from World War I, money flowed into the United States. By 1929, the United States represented 65% of global market capitalization, while Europe’s share had shrunk to 32%. However, the collapse of the American stock market after 1929 pushed the United States’ share of global market cap down to 40% by 1933, whence it recovered. Although there was some recovery in Europe the 1920s, the gold standard broke down in 1931 further reducing the globalization of global financial markets. Governments controlled industry during World War II, and after the war, France, Great Britain and other European countries nationalized their main industries while stock markets in Eastern Europe closed when the Communists seized power. By 1950, Europe’s share of global market capitalization had shrunk to only 18%.Dominance of the Anglo-Saxon Four

As Europe’s share of global market cap shrank, the four Anglo-Saxon countries’ share rose. These four include not only the United Kingdom and United States, but Canada and Australia. The United Kingdom played a smaller role in global finance after 1914 as it sold foreign securities listed in London to help pay for the war, but its global reach continued until the start of World War II in 1939. Neither the United States, Canada nor Australia suffered from the destruction of the world wars or the nationalization of its industries as occurred in Europe. By 1950, the three largest stock markets in the world were New York, London and Toronto/Montreal representing 75% of global market capitalization. By the late 1960s, Canada and the United States together represented 75% of global stock market capitalization. The Anglo-Saxon countries’ domination of global stock markets continued until the 1970s as is illustrated in the figure below which shows the Anglo-Saxon Four’s share of global market capitalization from 1900 to 2018. As can be seen, these four countries’ share of global market cap fell dramatically in the 1970s and 1980s. In the 1970s, the OPEC Oil Crisis, stagflation, the collapse of Bretton Woods and other economic problems began shifting the balance of power away from America. The Asian Tigers began exporting goods to the rest of the world. By the 1980s, globalization was back and economic power shifted toward emerging markets and Asia.The Rise of Asia

The main factor holding back Asia from dominating global stock markets until the 1980s was Asia. Shanghai had a stock market until the 1940s when it was closed down after the triumph of Communism, and India’s socialistic policies that preferred five-year plans over stock market-driven growth condemned its people to poverty for decades. Since 1970, Asia’s share of global stock market capitalization has increased dramatically. Export-led growth in Japan, Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore allowed those countries’ economies and stock markets to grow. Japan, Korea and Taiwan all went through stock market bubbles in the 1980s and in 1989, Japan’s stock market was larger than the United States’ and the largest company in the world was Nippon Telegraph and Telephone. NT&T’s market cap in 1989 was greater than the entire German stock market. In 1989, Asia represented 45% of the world’s stock market capitalization, Europe 22% and America 33%. However, in 1989, the stock market bubbles in Asia burst and Asia’s share of global market cap plunged to 16% by 1998; however, since 2000, both India and China have significantly increased their share of global market capitalization as Japan, Taiwan, and Korea have recovered from the crash of their stock markets in the 1990s. Asia grew at the expense of the United States up until the 2008 financial crisis and at the expense of Europe since then.The Asian Century?

Europe is no longer an engine of growth within the world economy and under Donald Trump, America’s willingness to pursue open trade with the rest of the world is in question. Were it not for the growth in the size of the internet stocks that dominate America’s stock market, Asia’s share of the world’s market cap would have grown even more during the past decade. How long before Asian stock markets become larger than America’s? Hong Kong, Shanghai and Shenzhen continue to attract new IPOs. Meanwhile, India is growing at a dramatic pace. At the current rate of growth, Asia will probably be larger than America by 2030 and have over half of the global market capitalization by 2040, if not sooner. And the more Europeans and Americans fight among themselves over trade, the sooner this is likely to occur.

It is important to remember that it was in 1929 that Dow Jones introduced their utility average. Utility stocks participated in the bull market for two reasons, leverage and a merger mania. Throughout the 1920s, utility stocks were consolidating at a furious pace. Before the 1800s, each city had its own utilities for electricity, gas, water and street railways. During the 1910s and 1920s, not only did all the utilities of a given city often consolidate into a single utility, but utility holding companies began acquiring utilities in different cities. Holding companies, as opposed to operating companies, could use leverage to acquire more and more utilities and operate across state lines, creating large companies whose profits grew rapidly. Samuel Insull epitomized this behavior as he consolidated utilities in Chicago and the surrounding area creating a utility empire which eventually collapsed in the 1930s.

Banks and Trust Companies Begin a Bubble

Until the 1920s, the primary assets of banks were small business loans. In the 1920s, banks began emulating department stores and went after individuals, offering their customers every type of service possible including personal installment loans, mortgage lending, and providing safe deposit boxes and trust departments. In addition to this, banks began underwriting securities, making loans on shares and provided margin lending for investors. Until the 1920s, unit banking, only allowing one location for any bank, was the law of the land, but in the 1920s some states, such as New York, began allowing branch banking and California allowed statewide banking. Thus, banks were encouraged to take over other banks. State banks could only operate within a single state and nationally chartered banks could only have one branch. When states began allowing state chartered banks to have branches, this put national banks at a disadvantage until the McFadden Act was passed on February 27, 1927 which put state and national banks on an equal footing. National banks located in states that allowed branching were also allowed to open branches. In exchange for this concession, national banks were not allowed to operate across state lines until the 1980s, though bank holding companies were granted this right in the 1950s. As a result, a merger frenzy occurred in the 1920s in which banks consolidated with other banks. Most banks were acquired with new shares, not with cash. Since it was easier to issue new shares than spend cash, bank stock prices started to rise rapidly. As the bull market pressed on, speculators borrowed money to purchase more shares and this helped to increase bank profits making the acquisition of other banks even more attractive. A virtuous circle of higher bank profits, more lending and rising bank stock prices from acquisitions created a banking bubble which could only end with a crash. On September 19, 1927, the NYSE allowed bank stocks to list and trade on the floor of the NYSE for the first time in 54 years, moving the banks out of the Department of Unlisted Securities. A dozen banks, including the Chemical National Bank, Bank of Manhattan and First National Bank listed on the NYSE, though all of them had delisted by 1930.Banks Stocks Become Unaffordable

Bank stocks traded at incredible prices until a wave of stock splits in 1929 brought shares back to earth. Sixteen New York City bank or trust stocks traded at over $1000 in 1929, and shares in the First National Bank of New York, which had already had a five-for-one stock dividend in 1901, traded at $8200 in September 1929. By contrast, average per capita annual income in the United States in 1929 was only $750. Bank stocks led the way in the bull market of the 1920s; however, this fact has been ignored because most bank stocks traded over-the-counter in the 1920s and there was no daily index of bank stocks that traders could keep track of. Since bank stocks and shares in trust companies were not listed on the NYSE and did not trade on a daily basis, only bid and ask prices were available for many of the companies. Moreover, bid and ask prices were only published on a weekly basis, so calculating a daily index was just not possible. Nevertheless, Standard Statistics calculated a weekly index of money center (i.e. New York) bank stocks. Moody’s started calculating a monthly index of Bank Stocks in 1929, at the height of the bubble, as well as an index of bank yields. In September 1929, as a result of the bubble, banks stocks had an average dividend yield of only 1.35%. Not surprisingly, the capitalization of banks exploded in the 1920s. Both the National City Bank of New York (later Citicorp) and the Bank of New York had capitalizations over $1 billion in 1929 placing them in the top 10 of all stocks in the USA by capitalization. This made those banks worth more than Sears, Standard Oil of New York and Chrysler, among others.Bank Stocks Collapse

The bigger they are, the harder they fall. Thousands of smaller banks went bankrupt in the 1930s and even shares in the larger banks fell by 90% or more in the next four years. The Banking Act of 1933 (Glass-Steagall) left banks heavily regulated until the 1980s. Regulation limited the profits of the banks and it took decades for them to recover. Even in 1985, S&P’s Money Center Stock Index was still below its 1929 peak, a level the Dow Jones Industrial Average had passed in 1954. Global Financial Data has put together several data series that enable us to track the capitalization of the world’s major stock markets from 1900 to 2018. With this data, we have calculated the global market capitalization of stock markets since 1900 and we have estimated values for Global GDP from 1900 to 2018. This enables us to calculate the total market cap of the worlds stock markets as a percentage of Global GDP and see how this has changed over the past 118 years.

Global Financial Data has put together several data series that enable us to track the capitalization of the world’s major stock markets from 1900 to 2018. With this data, we have calculated the global market capitalization of stock markets since 1900 and we have estimated values for Global GDP from 1900 to 2018. This enables us to calculate the total market cap of the worlds stock markets as a percentage of Global GDP and see how this has changed over the past 118 years.

Market Cap and GDP Data Sources

For most of the twentieth century, the two largest stock markets in the world were New York and London. The United States calculations aren’t limited to the New York Stock Exchange, but includes the NASDAQ, American Stock Exchange/New York Curb, regional exchanges and over-the-counter shares. The London Stock Exchange also had extensive listings of shares from companies in South Africa, Australia, and other countries that GFD used to complete its calculations of total world market cap. Global Financial Data’s US and UK stock databases include all the stocks listed on these exchanges, and we have summed up the market cap of these companies to get an exact measure of the breadth of the stock market in the US and UK over the past 200 years. In addition to this, GFD has collected stock market capitalization data directly from Japan, Canada, France, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, Switzerland and other countries. Lyndon Moore published an article detailing the market cap of 12 major world markets between 1900 and 1925, and between these sources, GFD has been able to make an estimate of the total market capitalization of the world’s stock markets between 1900 and 2018 (see series SCWLDCM).World Market Capitalization as a Percentage of World GDP, 1900 to 2018

Global Financial Data also has GDP data for every country in the world with many series extending back several centuries. We have summed this data to generate totals for world GDP going from 1900 to 2018 (see GDPWLD for nominal and GDPCWLD for real data). By dividing the world market cap estimates by world GDP we were able to generate the chart reproduced above. We can also use this data to generate a stacked chart showing how each country’s share of world market cap has evolved over the past 120 years. With the graph above, we can break up the history of global stock markets into several distinct periods: Pre-World War I growth, decline during World War I, the 1920s bull market, the 1930s depression, World War II and the post-war nationalizations, the Bull Market of the 1950s and 1960s, OPEC and inflation in the 1970s, European privatization and the Japanese stock market bubble in the 1980s, the rise of emerging markets and the dot-com bubble in the 1990s, the 2008 Financial Crisis and the recovery since then.70 Years of Financial Repression

Although few investors today may recognize it, the period from 1914 to 1986 was a period of financial repression by governments which actively intervened in financial markets and the economy and limited the growth of the stock markets both directly and indirectly. In July 1914, the world enjoyed a globalized economy in which the gold standard linked the currencies of the world and in which securities linked together the world’s primary exchanges. In the late 1800s, the world moved from a gold standard to a gold exchange standard. Under a gold standard, gold had to be literally shipped from one country to another to keep exchange rates in alignment with their gold parity rates, but under a gold exchange standard, individual securities could be bought and sold to bring currency rates back into alignment. In the mid-1800s, if there were a misalignment between the exchange rates of two countries, arbitrageurs would buy gold in one country and ship it to the other country to bring exchange rates back into alignment through supply and demand. By 1914, this was no longer necessary. Russian bonds, American railroad bonds, and the bonds of other countries were the international medium of exchange because these securities were traded on most exchanges in the world. If the exchange rate between the United States and Britain was out of line, securities could be bought in one country and sold in the other to realign the currencies. World War I and the intervention of governments that followed hindered the globalized securities market’s role of allocating funds between countries for the next 70 years. The exchange controls that were introduced in 1914 remained in place in one form or another for the next 70 years, limiting the ability of financial markets to move capital from one country to another. In addition to this, inflation after World War I, World War II and the OPEC crisis constrained the growth in financial markets because higher inflation rates mean higher discounts of future cash flows and thus a lower valuation of corporations. Governments nationalized many of the major sectors of the economy in Europe further reducing the capitalization of stock markets. It wasn’t until the privatizations of the 1980s and 1990s that the nationalized companies were returned to the private sector. Governments actively discouraged international cash flows and foreign investment through most of those 70 years, and instead of having an integrated global capital market, the world had a collection of stock markets divided by national borders. War was also a contributing factor to the reduction in the market cap of the world’s stock markets. World War I and World War II were total wars in which all of the nation’s resources were put to work to fight the war. National governments absorbed the available capital to fund their war effort as the National Debt/GDP ratio rose above 100% in many countries. After World War II, the experience of the Great Depression and World War II meant that economists used Keynesian ideology to justify their control of financial markets. Countries that went Communist completely eliminated stock markets. The tide in favor of capital markets turned in the 1980s when the Big Bang occurred in London and governments throughout the world privatized the industries they had nationalized. Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher both believed in free markets, not government control. Their beliefs eventually began to influence the rest of the world. In Germany, Deutsche Telekom was one of the largest privatizations in European history, and in France, after flirting with socialism and government control of major industries, Mitterand reversed course and privatized France’s banks, utilities and other industries. The rise of computers enabled NASDAQ to challenge the NYSE, not only in obtaining new companies, but in creating listings for a whole sector of the economy that grew dramatically as new companies tried to provide access to investors to the information technology revolution. This ultimately culminated in the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s. By the 1980s, the transition to global security markets was so complete that James Carville said, “I used to think if there was reincarnation, I wanted to come back as the President or the Pope or a .400 baseball hitter. But now, I want to come back as the bond market. You can intimidate everybody.” By the 1990s, for the first time in history, the ratio of global stock market capitalization exceeded global GDP. As long as the financial repression of 1914 to 1986 does not return, the ratio of global stock market capitalization to GDP is like to remain around 100% for decades to come.Pre-World War I Growth

The world’s stock markets were truly global in 1914. All of the major nations of the world were on the gold standard and a country like Russia could issue stocks and bonds simultaneously in British Pounds, U.S. Dollars, German Marks, French Francs, Dutch Guilder and Russian Rubles in each of those countries. Russian bonds were then used to arbitrage any misalignment of currencies away from their gold parity. The London Stock Exchange was the home to companies from all over the world, and the Paris and Berlin stock exchanges hosted shares from many companies not listed in London. Between 1865 and 1914, the market cap/GDP ratio in the United States rose from 10% to over 50%. In the United Kingdom, the market cap/GDP ratio rose from 20% before the railroad bubble of the 1840s to over 140% by 1914. Similar growth was apparent in other economies as well. This change was driven by a reduction in the outstanding debt of the United States, United Kingdom and other countries in the 1800s, which freed up capital to invest in individual companies. By 1914, the United States had eliminated most of its debts from the Civil War, but even more dramatic was the reduction in the debt of the United Kingdom. The century between the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 and the beginning of World War I in 1914 saw the UK government debt/GDP ratio drop from 230% in 1815 to 30% in 1914. All of that capital had been released to invest in the debt of American railroads, Russia and thousands of companies registered in London. Between 1914 and 1945, the UK government debt/GDP ratio returned to 230% of GDP and the British government not only redeemed many of the foreign securities that listed were in London, but restricted access to capital markets by both national and foreign investors.British National Debt as a Percentage of GDP 1688 to 2017

In addition to this, the sectors of the companies on the stock market underwent a dramatic change. The 1800s was the century of the railroads, but the 1900s saw growth in dozens of industries outside transports. By 1893, Standard Oil was the largest company in the world, and over the next century, other industrial companies, such as AT&T, IBM, General Motors, General Electric, Apple and others would take the title of the world’s largest company. However, the numbers fail to show how the fabric of global capital markets were ripped apart when World War I began. Before 1914, there was minimal government intervention in capital markets and investors were free to move capital from one market to the other. After 1914, the government actively controlled capital flows for the next 70 years.World War I

Globalization stopped on July 31, 1914 when almost all the world’s stock exchanges closed because of the declaration of war in Europe. The world’s stock markets were at the mercy of national politics for the next 70 years. The St. Petersburg Stock Exchange was closed down in 1917, not to reopen until the 1990s. The United Kingdom needed to pay for the war it fought against Germany, and sold its American railroad stocks, put a halt to new IPOs and focused on issuing bonds to pay for the war, not to promote corporate growth. The German stock market was closed until 1917, and even in neutral countries such as the Netherlands, capital markets were regulated. The Vienna Stock Exchange broke up into stock markets in Vienna, Budapest, Prague and other former portions of the Austrian empire. Each country suffered high inflation during World War I, reducing the market cap relative to GDP, and the war was followed by the global recession of 1920 which further reduced stock market cap relative to GDP. The German stock market never recovered and between Germany’s hyperinflation and the chaos of Weimar, Germany’s stock market cap fell from $5.8 billion in 1914 to $680 million in 1923, declining from about half of GDP to less than 5%. By 1920, there was no global stock market, but a collection of national stock markets.1920s Bull Market

Although many European stock markets saw dramatic declines in their value after World War I, the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada and France enjoyed dramatic bull markets in 1920s. Although the economies of the axis powers failed to recover from World War I, growth returned to the allied economies. By 1929, the US, UK and Canada represented about 80% of global stock market capitalization even though those three countries represented about 38% of world GDP. The Russian stock market had disappeared, Germany had collapsed from its hyperinflation, and Austria was broken up. Most of the increase in the market cap in the 1920s came from the stock markets of the allies. This was especially true of the United States and Canada which had suffered no destruction from World War I and whose industries grew rapidly in the 1920s as millions bought new automobiles, radios and other consumer goods. This can be seen in the graph below which illustrates the percentage of global market capitalization for each country from 1900 to 2000.National shares of Global Market Capitalization, 1900 to 2000

Depression and World War II

After 1929, the world’s stock markets collapsed. The Dow Jones Industrials lost almost 90% of its market cap. Smaller declines occurred in London and Montreal. France began nationalizing its industries under the Popular Front after 1936. Under Fascism, the state-controlled industry and the economy was directed toward rearming the country, not toward producing more consumer goods. National industries were favored and international trade was discouraged. The situation got even worse when World War II began. Private international capital flows ground to a halt. The government took over industry to fight the war and companies no longer raised fresh capital. World War II destroyed cities and factories and led to shortages in goods that had been plentiful a decade before. The end of World War II brought no relief. France and the United Kingdom nationalized their major industries. Two of the biggest UK companies of the 1800s, the Bank of England and the London and Northwestern Railroad became the property of the British government. Stock markets in eastern Europe were closed when the Communists gained power. The Frankfurt Stock Exchange reopened; the Berlin Stock Exchange did not. The French Stock Market’s capitalization as a share of GDP had been equal to 70% of GDP in 1914 and 1929, but by 1950 it was under 10% after the French nationalized its major industries. In the eyes of many, private capitalism had failed. Many believed that the experience of Russia and the war economy showed that the government could run the economy more effectively than the private sector and the ideas of Keynes were in the ascendant. Even an economist like Joseph Schumpeter wrote a book on the inevitable victory of socialism. Outside of the United States and Canada, many were ready to bury market capitalism forever.The Post-War Boom

1949 was the nadir of the anti-capitalism that dominated the world between 1914 and 1949. Bretton Woods laid a solid foundation for international exchange rates and the United States fought for open markets outside of the Communist bloc. Germany began its Wirtschaftswunder as its economy recovered, and Japan’s economy began its dramatic growth and recovery. Not only did the global economy grow rapidly between 1950 and 1970, but stock market capitalization recovered dramatically. World market cap grew from $163 billion in 1947 to $1.68 trillion in 1972, increasing over tenfold. The stock market’s share of global GDP grew from 25% to almost 50%. Nevertheless, in most European countries, the major industries of the economy remained under the control of the state. Although European economies allowed their currencies some freedom against the dollar after 1958, capital flows remained restricted. The world was still a collection of national stock markets, not an integrated global market as has existed in 1914. Governments still felt that they, not capital markets, knew best about how to manage the world’s economies.The Anglo-Saxon Four’s Dominance of Global Stock Markets

The United Kingdom and its three “offspring”, the United States, Canada and Australia, represented a growing portion of the total global market capitalization between 1900 and 1970. The United States, Canada and Australia suffered from neither the destruction of World War I and World War II nor the nationalizations that transferred transports, utilities, steel and other industries to the public sector. As the market cap of European countries’ stock markets shrank, the market cap of the UK, US, Canada and Australia grew relative to the rest of the world. The graph below shows the market cap of the UK, US, Canada and Australia as a percentage of global market cap from 1900 to 2017.Market Cap of the UK, USA, Canada and Australia as a Percentage of World Market Cap, 1900 to 2017

In 1900, the world was balanced between the United Kingdom (33%), United States (30%) and the rest of the world (37%) and by 1914, the United Kingdom had shrunk (27%) while the United States’ share had grown (33%). However, by 1928, the United States’ share of global market cap had grown to 60% and the Anglo-Saxon Four represented 79.7% of world market capitalization. As the chart above shows, the Anglo-Saxon Four represented between 70% and 80% of global market cap in most years between 1920 and 1970. Nationalizations in the United Kingdom after World War II shrank it share of global market cap from 24% in 1945 to 12% in 1950, but Canada’s share grew from 3.4% in 1945 to over 10% by 1953, in part due to investments in mining and energy. This means that any indices of global stock markets during those 50 years will largely reflect the behavior of the four Anglo-Saxon stock markets. Since 1970, however, other countries’ stock markets have grown in size and even though the Anglo-Saxon 4 still represented about half of global market capitalization in 2017, this percentage is significantly below the 70%-80% level it was at between 1920 and 1970.OPEC and Inflation

Although it seemed as if global markets had returned for good, no one could have foreseen the problems of the 1970s. OPEC quadrupled the price of oil in 1973 and placed an embargo on countries that had helped Israel during the Yom Kippur war. OPEC raised the price of oil further over the next few years, and increased the price of West Texas Intermediate crude from $3.41 in 1973 to $39 in 1980. The economies of the western world shrank and during the inflation and the global recession of the 1970s the capitalization of stock markets fell back to around 25% of global GDP. The market cap/GDP ratio for the world shrank back to the lows it had been at in the late 1940s. The 1970s saw inflation hit its highest level outside of war in almost every country in the world. Although inflation increased the absolute level of market capitalization, it reduced it relative to GDP because high inflation reduced the discounted present value of future cash flows to corporations. In 1973, the fixed exchange rate system that had prevailed for the previous 25 years collapsed. Although the goal was to return to a system of fixed exchange rates once the OPEC crisis was over, the world has remained in a world of flexible exchange rates. Although restrictions on capital flows kept money from flowing freely between the world’s security markets, the move to a world of floating exchange rates made the eventual restoration of global capital flows inevitably.Privatization, Emerging Markets and Dot-coms

But just as the nadir of the late 1940s laid the foundations for a dramatic increase in the stock market, so did the nadir of 1981. Governments responded to the first OPEC price increase by introducing price controls and other restrictions on the economy which failed miserably. In the 1980s, Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher and other world leaders favored market solutions over government regulations and the market boomed. Nippon Telegraph and Telephone was privatized in Japan and by 1989, it was the largest company in the world. Deutsche Telekom became the largest European privatization in 1995. Mitterand reversed course in the late 1980s and privatized not only the nation’s banks, but its utilities as well. Throughout the world, the government was privatizing the main industries of their economy both to promote economic growth and to raise capital for the state. The United States’ restrictions on interstate banking were lifted and thousands of banks merged to form multistate enterprises offering every type of financial service available. French stock market capitalization as a percentage of French GDP rocketed from under 10% in 1984 to 75% in 2001. In London, the Big Bang deregulated financial markets in London on October 27, 1986. If a single date could be selected when globalized financial markets returned to the world, this would be it. Under the big bang, fixed commission charges were abolished, the difference between stockjobbers and stockbrokers was eliminated and London moved from open outcry to electronic, screen-based trading. Driving all these changes was the relentless improvements in computer technology which gradually replaced trading floors. NASDAQ provided an example that the rest of the world followed, and during the 1990s, information technology grew to be one-third of the U.S. stock market as the dot-com bubble grew in size. In addition to this, the Asian Tigers of Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore and Korea used export-led growth to jump-start their economies. The Japanese economy grew rapidly until by 1989, its stock market capitalization was the largest in the world, briefly exceeding even that of the United States. This growth can be seen in the stacked chart above. Other emerging markets saw the success of the Asian tigers and began to emulate them. The Berlin Wall collapsed in 1989, the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991 and China began to open up to capitalism in the 1980s. The Shanghai and Shenzhen stock markets opened in 1990 and the St. Petersburg Stock Exchange reopened in the 1991. By the 1990s, almost every country in the world had eliminated barriers to capital flows. For the first time in 80 years, financial capital was free to flow between all the countries of the world. The debt of the United States was held throughout the world as trillions of dollars in government debt and stocks were traded on a regular basis. Today over 100 countries have stock exchanges where national securities can be traded.The Dot-com Bubble and Financial Crisis

In the United States, the dot-com boom propelled the NASDAQ to heights it had never seen before, and virtually any company that had .com in its name could IPO with billions of dollars in market cap overnight. By 2000, for the first time in history, the market cap of all of the world’s stock exchanges exceeded global GDP. The 1980s and 1990s saw the most dramatic growth in stock markets in history as the market cap/GDP ratio rose from 25% to 110%. However, the more open global markets led to financial crises because capital could easily flee countries that overborrowed. Eastern Asia suffered a financial crisis in 1997, Russia and Argentina in 1998 and the world when the dot-com bubble collapsed in 2000. Stock markets could not go up forever. The dot-com bubble collapsed in 2000 followed by the bankruptcies of Enron and Worldcom. Although increased capital flows meant that financial panics could quickly wipe out a large share of market cap, it also meant that markets could bounce back when optimism returned. Between 2002 and 2007, the market staged a remarkable recovery as the real estate boom replaced the dot-com boom. Once again, by 2008, total stock market capitalization exceeded GDP. When the dot-com bubble collapsed in 2000, world stock markets lost almost half of their market cap, but in 2008, stock markets worldwide lost over half of their market cap. In a matter of months, global stock market capitalization went from 110% to 50% of global GDP in the worst stock market collapse since 1929. Once again, the future of capitalism and stock markets was seemingly in question, but once again, as in 1949 and 1981, it was the perfect time to buy stocks. Central banks coordinated their intervention in financial markets, driving interest rates down to their lowest point in history. With interest rates close to zero, the discounted value of future cash flows rose pushing the stock market to new highs. Over the past ten years, stock have slowly climbed back and once again, global stock market capitalization exceeds global GDP.The Next Decade

Where will this chart go in the 2020s? Will stock markets continue to grow and stock market capitalization as a percentage of GDP stay above 100%, or are we headed for a triple top? The rise in stock market capitalization in the 1980s was driven by the privatization of public companies; the rise in the 1990s was driven by information technology; the rise before 2008 was driven by banks, real estate and greater liquidity; and the current rise has been driven by the central banks of the world pushing interest rates to zero. The world has changed dramatically since 1914. Before 1914, financial markets were left to their own devices and it was felt that governments should leave financial markets alone to allocate capital between the countries of the world. In the period between1914 and 1981, growth in the market cap/GDP ratio was constrained by war, inflation, nationalization, controls on international capital flows, and general financial repression by the governments of the world. In 2018, the central banks of the world have become the protectors of financial markets. Hundreds of millions of people have invested their pensions in the stock market and will be dependent upon them when they retire. A crash in the stock market will hurt the savings of hundreds of millions. Of the primary causes of financial repression during the period between 1914 and 1986, none of them, war, inflation, nationalization or controls on international capital flows look likely to reappear in the 2020s, so in the absence of financial repression, the global market cap/GDP ratio should stay around 100% or above. But then, in 1913, no one was predicting what happened in 1914. Global Financial Data has made major revisions to three of its popular indices, the Dow Jones Transport Average, the S&P 500 Composite and the S&P 500 Composite Total Return Index.

Global Financial Data has recently calculated its own GFD Index for Railroad stocks in the 1800s. Using data GFD has collected on the price of shares, dividends paid on shares and the number of shares outstanding, GFD has calculated a cap-weighted index of the price and total return to railroad shares from 1832 until 2018. In each year, Global Financial Data chose the top 40 companies by capitalization, then narrowed the list down to the top 25 companies by liquidity and used those 25 companies to calculate GFD’s Railroad Index. The index is illustrated below.

Global Financial Data has made major revisions to three of its popular indices, the Dow Jones Transport Average, the S&P 500 Composite and the S&P 500 Composite Total Return Index.

Global Financial Data has recently calculated its own GFD Index for Railroad stocks in the 1800s. Using data GFD has collected on the price of shares, dividends paid on shares and the number of shares outstanding, GFD has calculated a cap-weighted index of the price and total return to railroad shares from 1832 until 2018. In each year, Global Financial Data chose the top 40 companies by capitalization, then narrowed the list down to the top 25 companies by liquidity and used those 25 companies to calculate GFD’s Railroad Index. The index is illustrated below.