Brazil went through an economic bubble in the 1880s that burst in the 1890s during the first Brazilian military dictatorship. Two finance ministers in Brazil adopted a policy of unrestricted credit for industrial investments in the 1880s. This led to speculation, fraudulent IPOs, inflation and ultimately, a crash that lasted from 1889 to 1893.

Brazil went through an economic bubble in the 1880s that burst in the 1890s during the first Brazilian military dictatorship. Two finance ministers in Brazil adopted a policy of unrestricted credit for industrial investments in the 1880s. This led to speculation, fraudulent IPOs, inflation and ultimately, a crash that lasted from 1889 to 1893.

Saddle Up

The word “encilhamento” means to saddle up or mount a horse and refers to jumping on a get-rich-quick scheme. Brazil had slowly industrialized during the 1800s and founded corporations that developed rail transport, gas lighting, banks and steamships. The “Land Law” of 1850 and the “Barriers Act” of 1860, which limited access to agricultural land by slaves and immigrants, had held back the country’s growth. Under the Encilhamento, big rentiers were better able to invest their money where it provided the highest rate of return. Merchants, businessmen, financiers, politicians and tradesmen could invest their money in either local companies or in Brazilian companies that listed in Paris or London. A new banking act was passed in 1888 which reversed the 1860 Barriers Act, and in the same year, slavery was abolished after a long campaign by Emperor Pedro II. Changes in the Land and Real Estate Law occurred in 1889. Government debt fell, reducing the issuance of government bonds and freeing up capital to flow into equities. With all of these positive changes, stock prices in Rio de Janeiro started to boom. On November 15, 1889, a military coup d’etat established the first Brazilian Republic. It overthrew the constitutional monarchy of the Empire of Brazil and Emperor Pedro II. Unfortunately, this also marked the apex of the bull market and the Brazilian stock market declined over the next four years. Ruis Barbosa was appointed the new Finance Minister under the Republic, and he instituted many of the changes he had promised to pop the bubble. This included introducing a new banking bill and introducing a Central Bank to regulate the money supply.The Baring Crisis

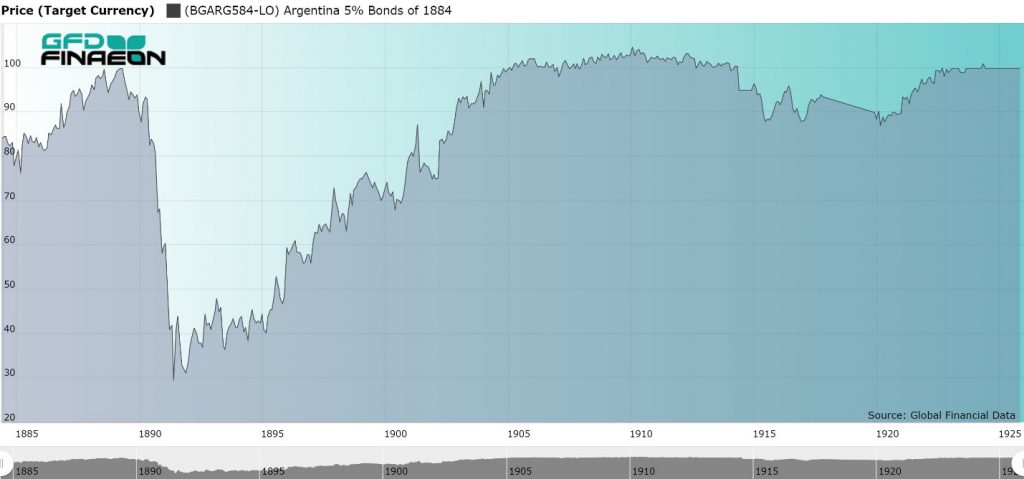

During the 1880s, there were huge capital flows from London into South America with the current account deficit of Argentina averaging 20% of GDP between 1884 and 1889. During those years, the Argentine money supply grew at the rate of 18% per year, inflation averaged 17% and the paper peso depreciated at the rate of 19% per annum. By the end of the decade, Argentina was the fifth largest sovereign borrower in the world; 40% of foreign borrowing was going toward debt service and 60% of imports were for consumption goods. Argentina defaulted on £48 million in debt in 1890. The military tried to overthrow the Argentine government on August 6, 1890, but failed. After the crisis hit, real GDP in Argentina fell by 11% in 1890 and 1891. The collapse this caused in the price of Argentine sovereign bonds that resulted is illustrated in Figure 1. Figure 1. Argentina 5% Bond of 1884, 1884 to 1925

Figure 1. Argentina 5% Bond of 1884, 1884 to 1925

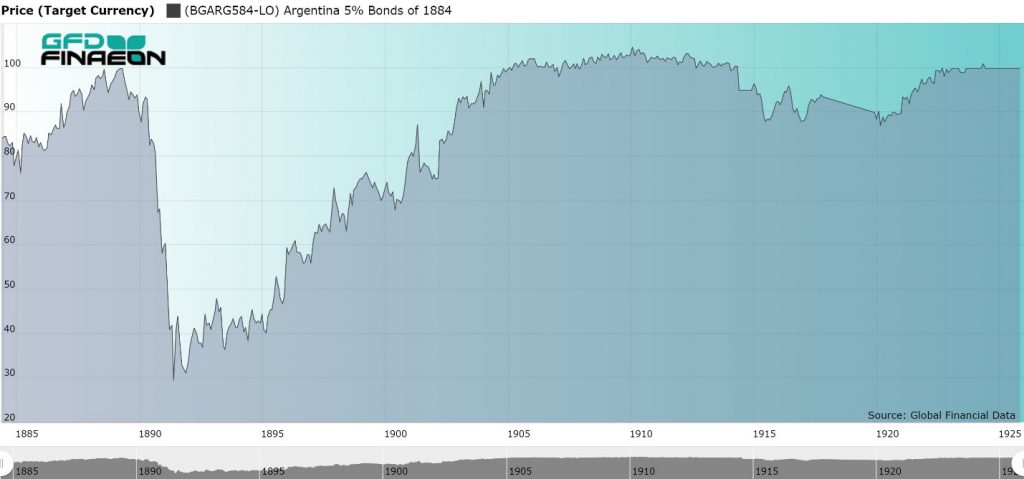

Figure 2. Brazil 4.50% Bond of 1883

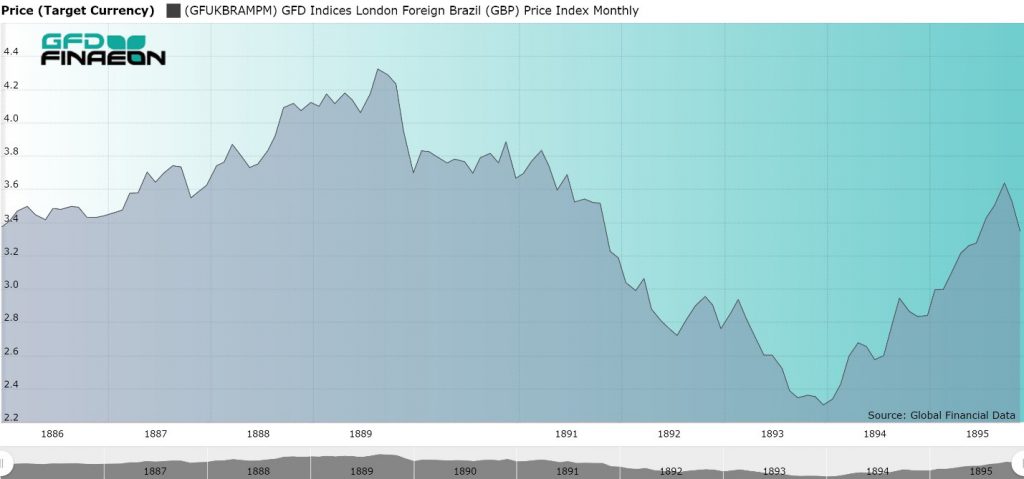

As the Baring Crisis spread throughout South America, the bubble that had built up in Brazil burst. This led to a steady decline in equity prices in the years that followed. Brazilian share price steadily declined from 1889 to 1893 as is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Brazil Stock Price Index, 1885 to 1895

The Baring Crisis led to a world-wide depression which, although it was not as severe as some of the other depressions of the 1800s, affected Europe, the United States and South America. Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay were all affected by Argentina’s default and the Baring Crisis that followed. The crisis spread to South Africa and Australia, and in the United States. The global economy suffered throughout the 1890s. No country was left unaffected. Brazil may have suffered from the Great Depression of the 1890s, but so did every other country in the world.