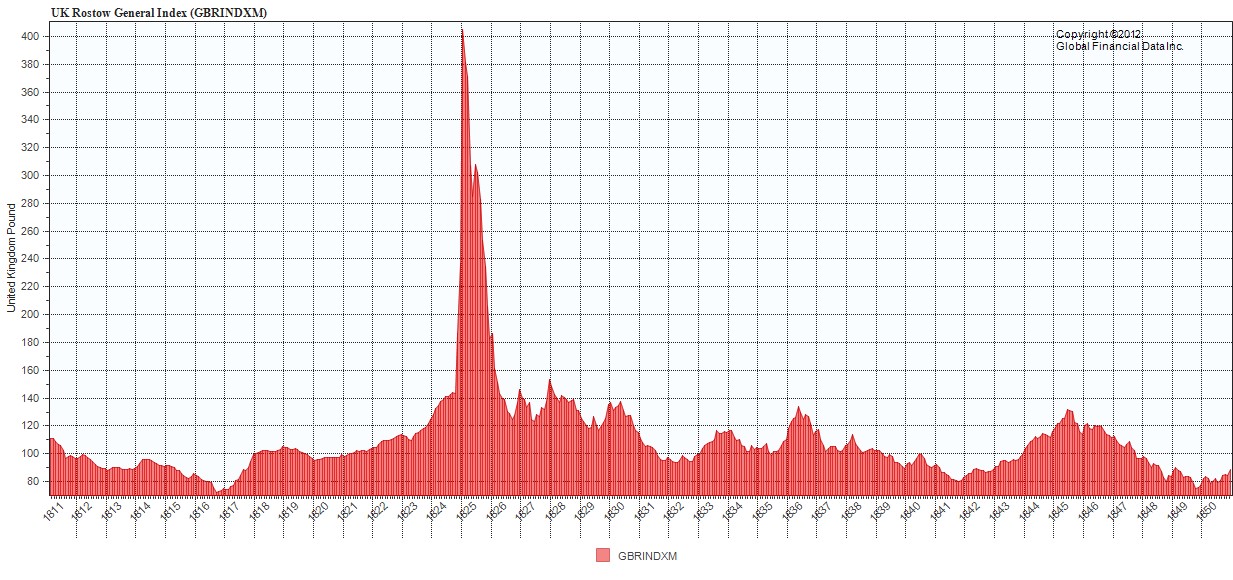

Long-term data allows you to make long-term predictions. Given the performance of the stock market over the past 300 years, there appears to be a high probability that the next roaring Bull market for equities will occur in the 2020s. If you look back at the stock market over the past 350 years, you’ll find that in each Century, the Twenties have always enjoyed bull markets in equities; this rings true for the 1720s, the 1820s and the 1920s. Unfortunately, as we’ve seen with bull markets across many asset classes, these dramatic bubbles came crashing down by the end of the decade.

Although there is no reason why events a hundred years ago should determine events one hundred years forward, similar situations can produce similar results. As the saying goes, history doesn’t repeat itself, it rhymes. What were the situations that produced the Bull Markets of the 1720s, 1820s and 1920s? Could this pattern repeat itself in the 2020s?

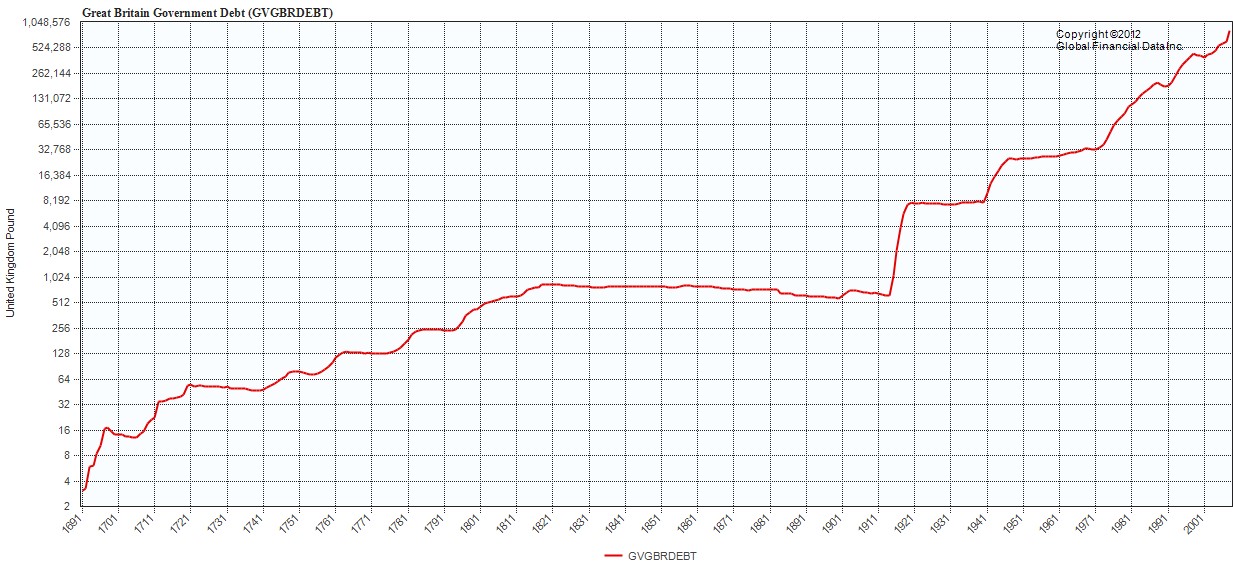

The graph below shows the growth in UK Government debt from 1691 on. The rise in debt through 1720 that resulted from the War of the Spanish Succession is quite visible, as is the quadrupling of government debt during the Napoleonic Wars, the increase in debt during World War I and World War II, as well as the increase in debt that has occurred in the UK since 1970. Debt drives bubbles and government debt creates the biggest bubbles of them all.

THE BUBBLE OF THE 1720S

The 1720s are best known for the South Sea Bubble in London, but in fact, there were similar simultaneous bubbles in both Amsterdam and in Paris. The War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714) was a European-wide war fought over whether Spain and France should be united under a single monarchy. This war added to the government debts of all the European countries and after the war was over, the government wanted to find a way to avoid the debt they had created.

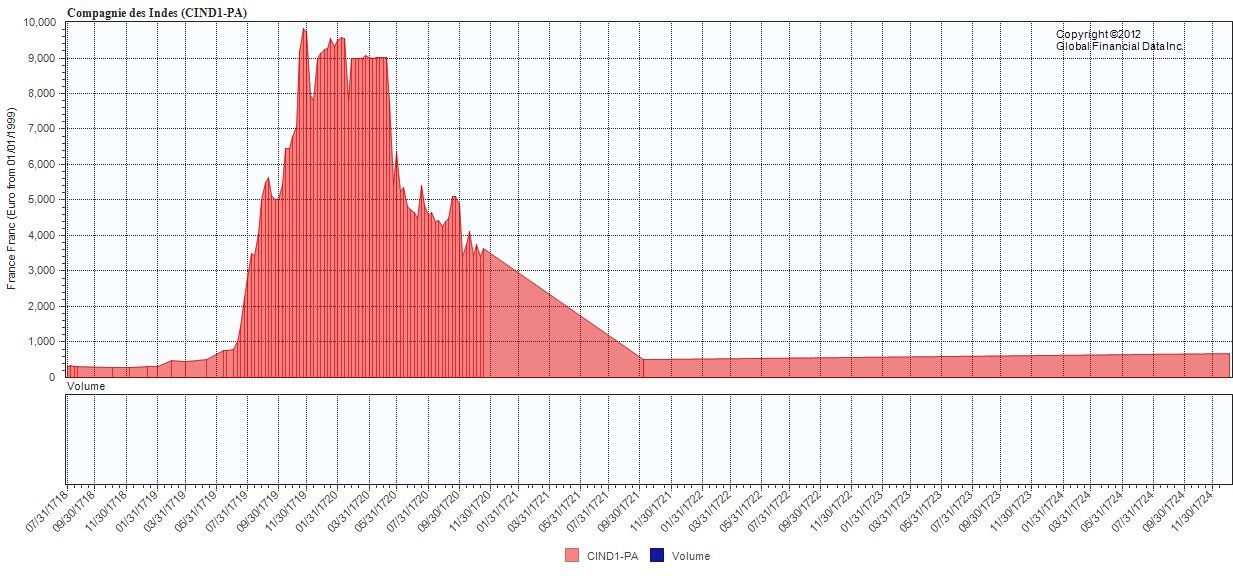

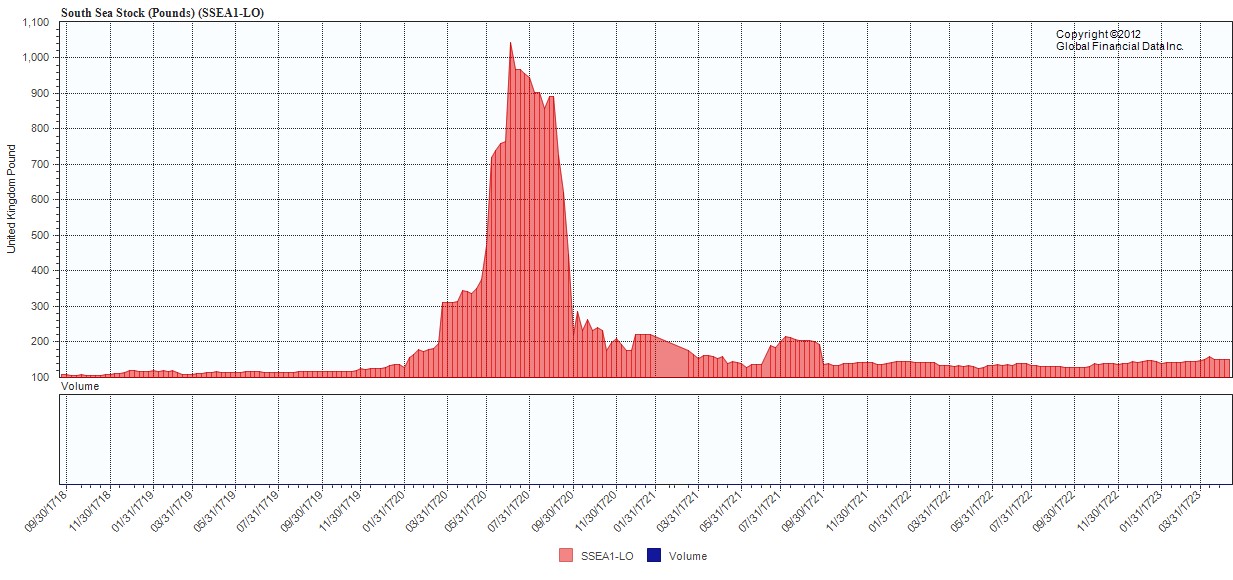

In both Paris and in London, governments found ways to convert outstanding government debt into equity in trading companies whose monopolies would produce large returns to shareholders, but instead this created bubbles for the Compagnie du Mississippi in Paris and the South Sea Company in London. Although the South Sea Bubble is the more famous of the two, the Compagnie du Mississippi stock was the bigger bubble with share prices going from 282.5 in November 1718 to over 10,000 by November 1719. The South Sea Stock’s increase from 116 to 1045 seems small by comparison.

In both France and in Great Britain, the causal factor of the first global stock market bubble was the government trying to rid themselves of their excessive debt load and stimulating the economy through inflation and a debt-equity swap. The government benefitted because it reduced its debt, and many speculators benefitted as well. But the long-run costs outweighed the short-run benefits. As a result of these bubbles, the stock market was seen as a speculative trap that hurt investors, and the “Bubble” Laws that were passed in England after the bubble ended stifled investment in legitimate companies until the Canal stocks became a source for capital at the end of the 18th Century.

THE BUBBLE OF THE 1820S

Stock markets in both London and Paris remained quiescent for the rest of the 18th Century. The French Revolution of 1789 led to the Napoleonic Wars which not only engulfed Europe in war, but as always, produced huge debts. After the Napoleonic Wars ended in 1815, London was awash in liquidity. During the wars, the South American colonies had declared their independence from Spain while Spain was ruled by Napoleon’s brother, Jose Bonaparte.

Since South America was one of the primary sources of gold, silver and other minerals, the newly-born countries used this fact to borrow money from Europe, using the future revenues from gold and silver as a guarantee for the bonds and equities that were being issued, just as the South Sea Co. and Mississippi Co. had used their expected monopoly trade revenues to justify the bubble of the 1720s. The end result was the same, liquidity flowed into the new government bonds and stocks, and having forgotten about the bubble of the 1720s, the bubble of the 1820s ensued.

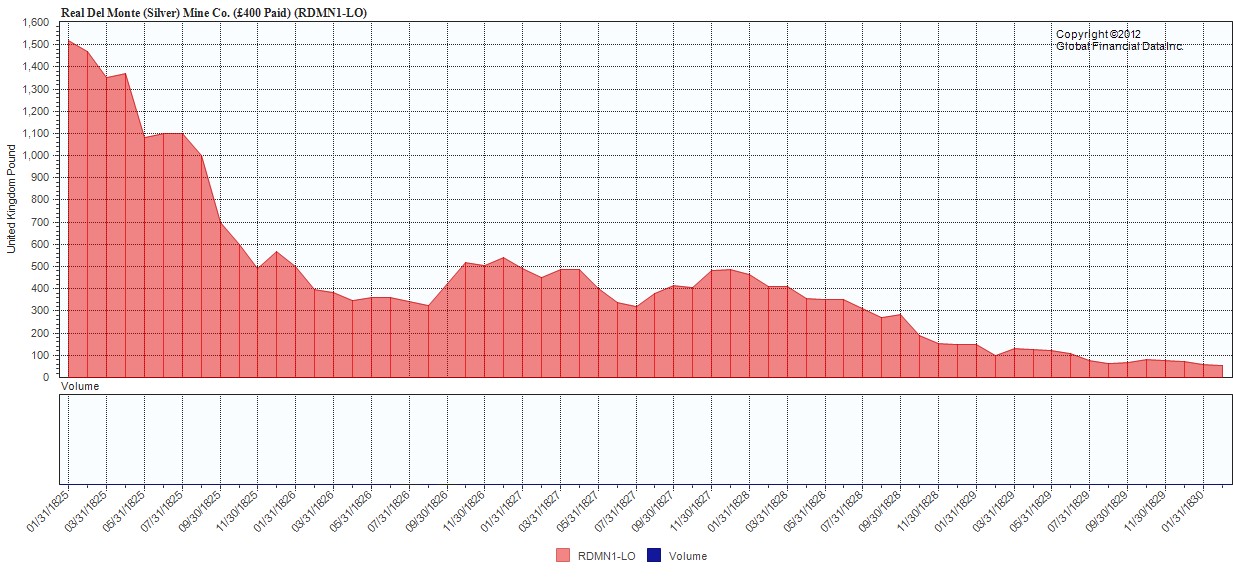

Most of the price changes occurred in mining stocks. Real del Monte of Brazil lost over 90% of its value very quickly once it was realized the mining revenues that were anticipated would never occur.

Of course, countries like Spain, Portugal and Greece in Europe (sound familiar?) and Chile, Brazil, Argentina and others in South America all defaulted on their debts. Countries that never existed, such as Poyais, could no longer issue debt to gullible investors (please see article The Fraud of the Prince of Poyais on the London Stock Exchange for further reading).

As in the 1720s, excessive government debt led to excessive liquidity. The prospect of large profits abroad encouraged new investments. As money flowed into South America, a bubble was created that inevitably crashed. After two such misadventures, you would think that investors would have learned their lesson.

THE BUBBLE OF THE 1920S

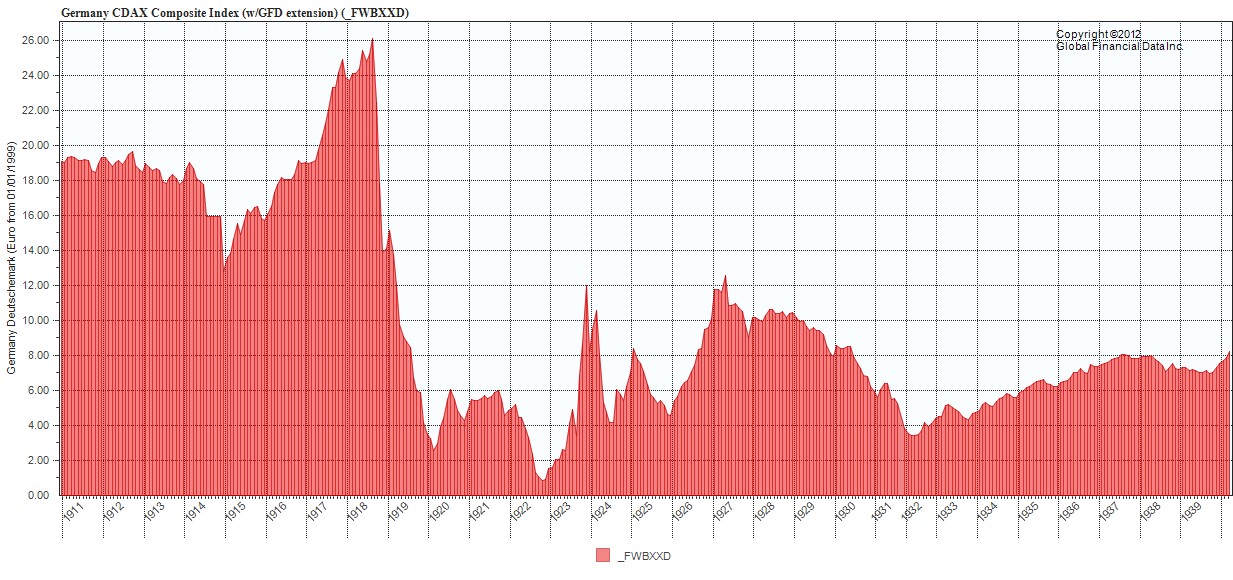

Between 1914 and 1918, Europe again fell into war. This generated large debts for all countries involved, brought an end to the Gold Standard, and de facto defaults on government debts through inflation. Germany’s hyperinflation wiped out investors in government debt and created severe losses for shareholders.

Although we think of the Roaring Twenties as a period when stock markets were booming worldwide, this simply wasn’t the case. Northern European stock markets and Japan didn’t participate in the bull market of the 1920s at all.

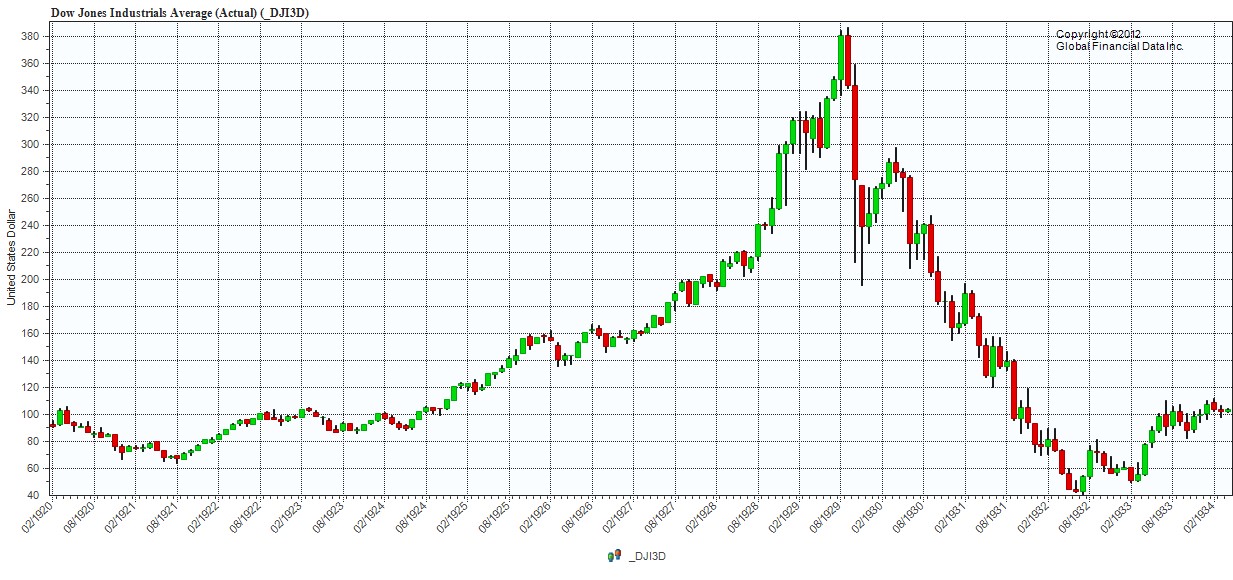

Americans pulled their money out of Europe and invested it in the United States, and the great Bull Market of the 1920s ensued, only to come crashing down by the end of the decade. As with any bubble, since the fundamentals made the bubble unsustainable, a crash was inevitable. However, the global economic community was unable to address the financial dislocations created by World War I. The combination of poor monetary policy, economic dislocation, the inability of the international community to work out solutions to these problems, and the unwillingness of the isolationist United States to take leadership on these global economic issues contributed to the problem. The global economy went into a death spiral from 1929 to 1932 and pulled financial markets down with it.

As in the 1720s and in the 1820s, government’s unwillingness to deal with the debt it had created, and its inability to reach a political solution to the problems it had created meant that the markets were forced to deal with the consequences of government’s failures.

THE BUBBLE OF THE 2020S?

The bubbles of the 1720s, 1820s and 1920s were amazingly similar. In each case wars had created excessive government debt. Governments inflated their way out of their debts in France in the 1720s, countries like Austria in the 1820s, and Germany in the 1920s. Investors found new investment opportunities abroad, in trading companies in the 1720s, South American companies in the 1820s and in the United States in the 1920s. Both government debt holders and equity investors lost money as a result of these bubbles as governments defaulted on their debts and share prices collapsed. In each case it was decades before markets began to recover.

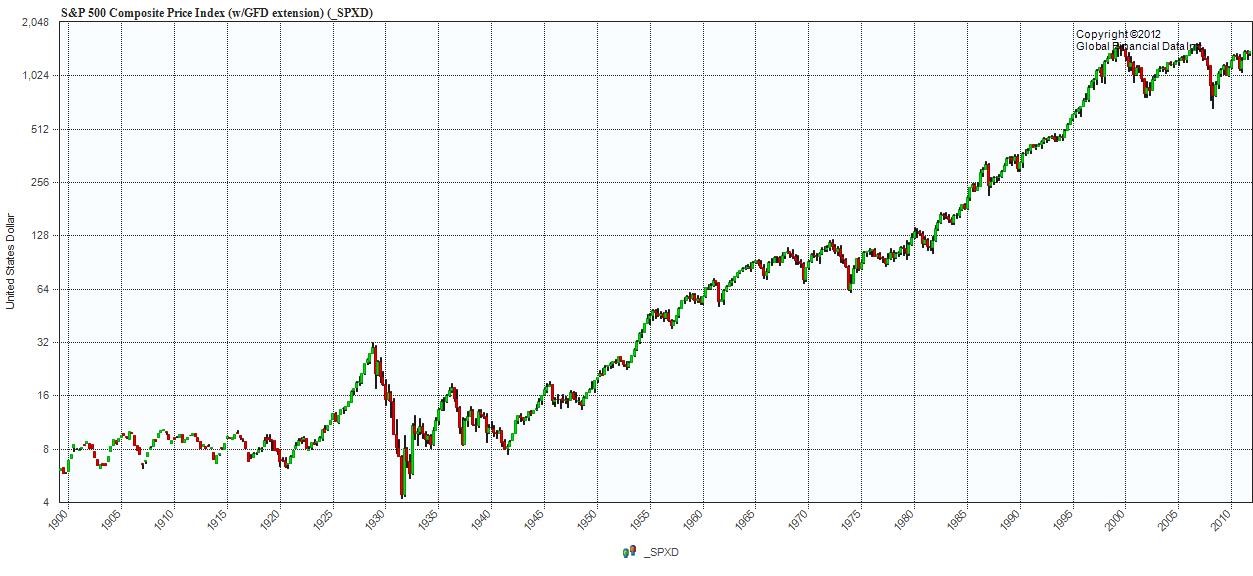

In addition to the century cycle we have discussed here, there is a pattern covering several decades that would also point to a significant move up in the markets in the 2020s. Since 1900, the S&P 500 has had three major moves up and three plateaus. The first plateau existed from 1900 to 1920 before the bull market of the Roaring Twenties began. Stock collapsed during the Great Depression, and then sank back until the next Bull move began in 1941. A second plateau occurred between 1966 and 1982 before the Bull Market of the 1980s and 1990s. Stocks have been stuck in another plateau since 2000. Could the market break out for a similar Bull Market after another 20-year plateau?

Could a similar bubble occur in the 2020s? There certainly are some similarities. Government debt has been piling up in Europe, Japan and the United States at unprecedented rates. Government bonds pay extremely low rates so investors are looking for alternatives. Emerging markets provide higher growth rates than the developed world and opportunities that are unavailable in the more mature economies. Finally, equities have provided low or negative returns for the past 25 years in Japan and for the past 15 years in the US and in Europe.

Governments could try to reduce their debt burden through inflation or some other form of default. Money might pour out of the trillions of dollars of government debt that have accumulated and go into equities, especially if new technological innovations occurred, or changes in developing countries made investments there more attractive. As stocks rose in price and more money poured in, a new bubble could develop.

Government debt has increased throughout the world. Many countries are able to avoid the problems of excessive debt because interest rates remain low, but there is no guarantee interest rates won’t rise at some point. If they do, the cost of servicing the debts that countries have built up could become excessive. At that point, investors might abandon government debt of the developed countries as they did in the past and invest their money in foreign growth stocks. This could be either “established” emerging markets such as the BRICS, or frontier markets in Africa. A bubble in African stocks is not inconceivable. Some of the best performing economies of the past few years have been in Africa and as the growth-stifling dictatorships that dominated Africa for the past 50 years give way to growth-oriented democracies, investors may seize on “once-in-a-lifetime” opportunities. Whether this will occur or not remains to be seen, but the possibility is there.

Any flight to emerging stocks out of reaction to the risks of government debt and underperformance of the debt-laden developed economies will inevitably lead to a crash. Financial bubbles occur where the fundamentals don’t justify the changes in equity prices. Perhaps investors have learned from the past, and any such bubble will be snuffed out before it begins. Then again, history would tell us a different story.

Will a bubble in the roaring 2020s mimic the bubbles of the 1720s, 1820s and 1920s? Only time will tell…